Can growing peas in the winter help the Colorado River?

CSU researchers show promising results from first year studying the viability of pairing winter peas with water conservation payments

story by Christopher Outcalt

published March 7, 2024

A few miles north of downtown Fruita, not far from the winding, overburdened Colorado River, Professor Perry Cabot oversees a research program at Colorado State University’s Western Colorado Research Center in the Grand Valley with two goals top of mind: How do we consume less water, and how do we keep agriculture profitable while doing it?

“To me, the outcome of my research program needs to achieve both of those goals,” said Cabot, who specializes in irrigation and water management issues. “Otherwise, all I’m doing is trying to solve one problem while making the other problem worse.”

Recently, Cabot, who runs numerous projects on the research farm, has found something that appears to fit his two tenets well: winter peas.

Cabot, along with CSU colleagues Dan Mooney, an economist, and Jessica Davis, an agronomist, have produced initial data showing that western Colorado farmers could profit in the near future by harvesting winter-grown peas in the spring and then enrolling that land in a water conservation program for the rest of the season. The group is now studying the crop for a second year.

The research team started the project, a three-year study, in fall 2022. The idea was to examine the viability of planting peas in the fall on Colorado’s Western Slope.

Farmers in western Colorado rely on the Colorado River, which provides water for 40 million people across the West and is used to irrigate millions of acres of farmland. Climate change, however, has left less water in the river, and water managers from Colorado to California are trying to figure out how to do more with less. Finding viable alternative crops that require less water is one option, Cabot said.

“I’m always thinking about how this compares to what we do right now,” Cabot said. “Alfalfa is the biggest consumer of water; farmers grow it because economically it’s the best thing to grow. So, we’re trying to be competitive with alfalfa.” He added, “I want to be in the world of viable alternatives, which to me means economically viable.”

A lot of potential

From the outset, winter peas presented a few promising possibilities.

Notably, the U.S. Department of Agriculture had just approved new varieties of food-grade quality peas that were hardy enough to withstand winter. This meant that, for the first time, peas planted in the fall could be grown for human consumption, not just for animal feed. (Previously, food-grade quality peas were only grown in the summer.) What’s more, there’s a growing market for peas, which are used for protein in many plant-based meat substitutes and dairy alternatives.

Then there were the potential water benefits. Growing a crop on a fall-winter-spring cycle — as opposed to through the heat of the summer — is more water-friendly in a few ways. Winter crops don’t require as much irrigation, there is less water lost through evaporation, and the water that is consumed is shifted to a less demanding time of year. (In the summer, for example, demand for municipal water increases.)

“With winter peas, most of the water use is in early spring when there’s a lot of water in the river,” Mooney said. “You’re not using that irrigation water in the summer when it’s super-hot out and when everyone else is irrigating — and when the cities also need water.”

The final element of the equation was the existence of a regional water-savings program known as the System Conservation Pilot Program, or SCPP. Run by the Upper Colorado River Commission, an interstate water administration agency, the voluntary program offers farmers money in exchange for using less water. Typically, that means leaving a field fallow. However, Mooney said, there are reasons why a farmer might be interested in this kind of program but not want to fallow a field — weeds can become a problem, and the health of the soil can deteriorate.

Growing a cover crop is a regenerative practice that can help control weed growth and improve soil health, but those crops are often not a source of direct income, Cabot said. “People talk about cover crops, but the rub is that they use water and it’s hard to quantify the benefits,” he said.

Cabot is most interested in projects that can produce more tangible financial results. Growing winter peas, for example, results in a sellable product. “We don’t really know yet the financial value of soil health,” he said. “I want more immediate solutions.”

In the ground testing

Information already existed on how peas performed in places such as Idaho, Washington, North Dakota and Montana, but there was little data for Colorado. During the project’s first year, the team began to fill that gap. They grew different varieties of peas with different shut-off dates for spring irrigation. They also tested the crop both with and without fertilizer treatments.

The peas grew surprisingly well, Cabot said. “We executed our protocol very well, and the yields we showed were indicative of that,” he said. “We had commercially comparable yields.”

Mooney then incorporated three potential water lease payments and calculated the net profit under each scenario. “Farmers can make money off of it — if they combine winter pea production with those water conservation program payments,” Mooney said. “Which is good news.”

The team plans to continue to refine its work over the next two seasons, looking for ways to optimize the crop. (The Colorado Water Conservation Board provided funding for the project’s first year.) “My goal, after we have a little better handle on it, is to write a production manual,” Davis said. “Not just how to grow winter peas — the manual would also include a production budget and hopefully some marketing options.”

For farmers in eastern Colorado, Davis said, there are some potential connections to markets in Nebraska. Western Colorado is a little trickier, she said. “We’re getting a better handle on the market opportunities,” she said. “You don’t want to spend all your profit on transportation costs.”

The next round of peas went into the ground at the Grand Valley Research Center in the fall. Eventually, with a better understanding of the potential market for peas and how the crop might integrate with water conservation programs, the team hopes to have detailed recommendations for interested farmers in the near future.

“We feel like we can give a producer confidence that they can grow the peas and show them here’s how much money you’d need to make on the water — and then give them the business plan that would be associated with this alternative,” Cabot said. “I feel confident our work will continue to provide that.”

SOURCE Special Report: Solving the water crisis

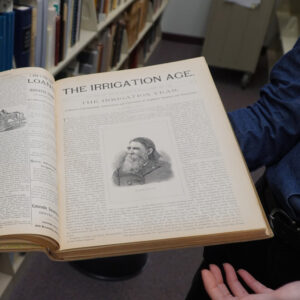

CSU has been at the forefront of hydrology for more than a century since Elwood Mead, the namesake of America’s largest reservoir, became the first head of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in 1883. This special report from SOURCE explores the research happening at CSU and provides insights into the ongoing water crisis across the country and around the globe.