The story of water

How CSU’s water archivist curates Colorado’s complicated, controversial history

podcast by Stacy Nick

published March 7, 2024

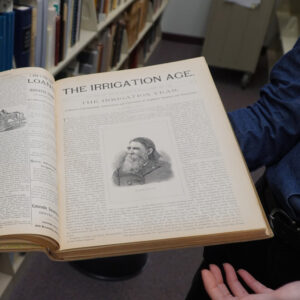

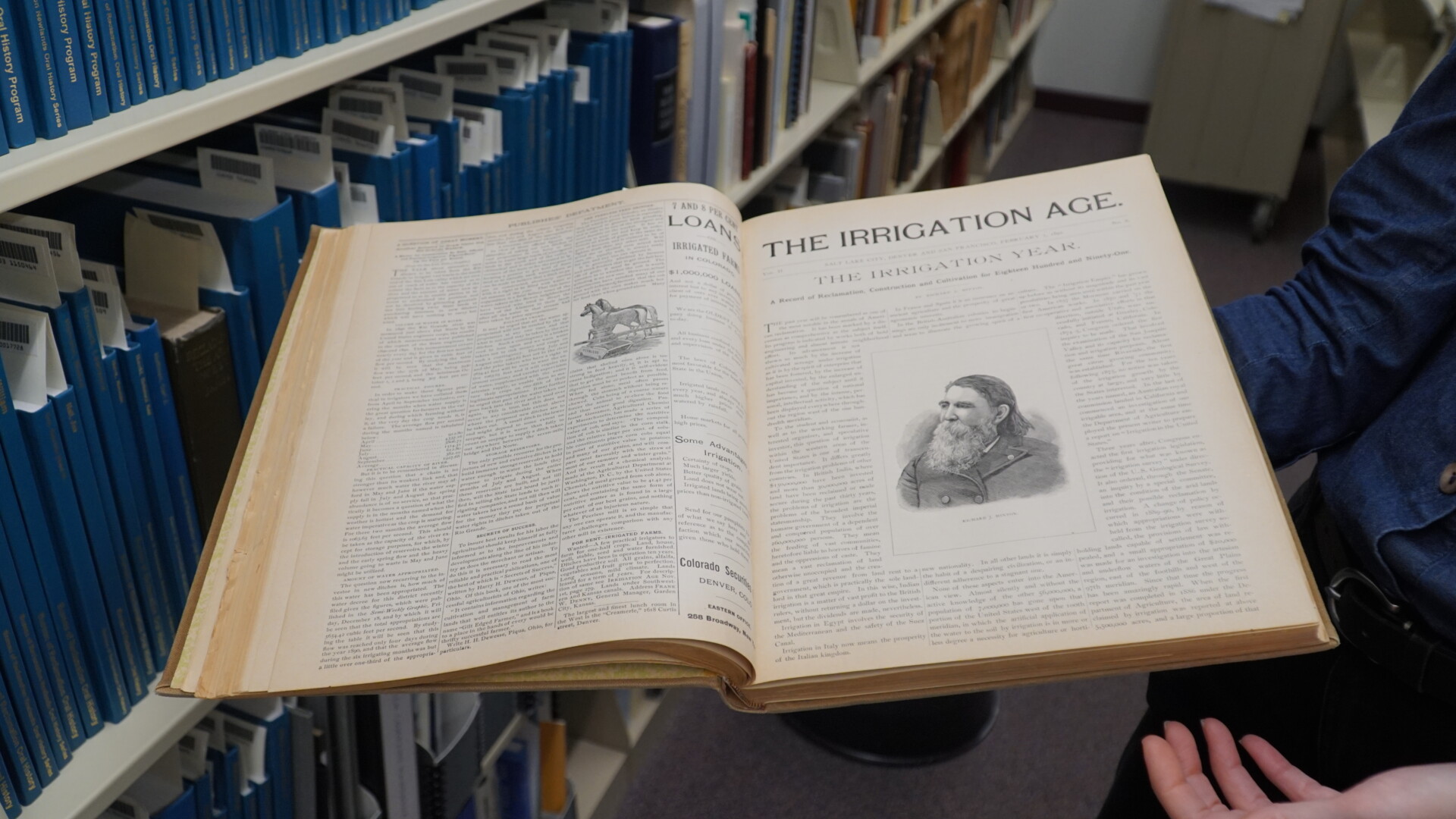

On the second floor of Colorado State University’s Morgan Library, there are hundreds of boxes and stacks of books all dedicated to just one topic — water.

There’s a copy of the Colorado River Compact, the landmark document that governs how the seven states that make up the Colorado River basin allocate its water. There are letters regarding Elwood Mead — Lake Mead’s namesake — who developed the country’s first irrigation engineering class while a faculty member at CSU before going on to oversee the construction of the Hoover Dam.

There are also documents that point to the destructive power of water, such as photographs of the damage from the 1997 Spring Creek flood, which put much of CSU’s main campus under several feet of water and caused more than $140 million in damage to the campus.

Each marks a moment in Colorado’s long and complicated water history. And it’s all just a part of CSU’s Water Resources Archive.

Created in 2001 as a joint effort of the University Libraries and the Colorado Water Center, the archive features historic documents related to Colorado’s water resources. Patty Rettig has been the head archivist for the program since it began, building the collections that, at last count, totaled an estimated 3 million items — from maps and photos to meeting minutes and contracts.

Rettig recently spoke on CSU’s The Audit podcast about her role and the importance of preserving the state’s water heritage.

Host Stacy Nick: Patty, thanks so much for being here.

Patty Rettig: Well, thank you so much for inviting me.

For folks wondering what exactly a water archivist does, talk a little bit about your role. Why does water need an archivist?

The role of a water archivist has two parts. One being the archivist part and the other being the water part. The part about being an archivist is what archivist do across the world, which is collect and preserve historically important documentation. That might be all kinds of those unpublished documents, the maps and photographs you were talking about.

In terms of the water portion of my role, that’s where the subject focus comes in. I focus primarily on Colorado water history. That means water across the state of Colorado, surface water, groundwater, different topics within water such as law, irrigation, engineering, endangered species, education, all those kinds of different topics related to water.

Why does water need an archivist? Because water is basic, it’s fundamental to everything we do. Lots of decisions have gone into manipulating our water. So much has happened with water, especially in Colorado, with moving it, getting it to where people want to use it, need to use it, making sure it’s available for wildlife and the environment, as well as being concerned with the quality of that water. Lots of decisions and changes have gone on with that, and tracking its history helps us understand how we got to where we are today.

The archive was initially funded by insurance payments after the 1997 Spring Creek flood. Is that correct?

Yes. My understanding is that once the university received those payments, they essentially set up a pot of money that different departments or individuals could apply for. It was Robert Ward who was at the time the director of the Colorado Water Center. He and some other folks put together a proposal to start a water resources archive. It got funded. That was about 2000. Then as of July 1st, 2001, the beginning of the fiscal year, that’s when the funding started, and the Water Resources Archive began.

He and others had the idea of starting a water resources archive at CSU before that but were not able to get the money or there wasn’t money available. But he had already been talking with the history department and the libraries to get something started. In the meantime, he had been accepting and collecting in his office various archival materials and collections that people had offered to him that he didn’t want to see get lost to history. So, that idea, even before the funding came through, existed on campus.

Your job is to decide what’s important to save and what isn’t. How do you know whether a document is important and worthy of archiving? You know, for someone like me who is a bit of a packrat, that seems really stressful.

Yes. That is one of the biggest challenges in doing this job is deciding what to save and, more importantly, what not to save. Because if we decide something shouldn’t be saved, it could be gone forever, and maybe we didn’t know. So yes, having an archivist who is making those decisions really can influence potentially how history is written or how history is understood. So, we take that very seriously.

One example of how we make decisions — a few months ago, I was offered a collection from somebody I didn’t know, a woman whose husband had been an engineering consultant, and they lived in Boulder. I talked with her. I visited with her in Boulder to see what she had from her husband, his basement office, as well as a storage room. I was not familiar with this person, but I did the research. I found out what I could, I talked with his wife, and I basically had dozens upon dozens of boxes to go through, things that he had already boxed up to put in storage from his consulting career, as well as shelves of materials and several desks in the office down in the basement there, as well as piles of floppy disks and CDs.

Oh my gosh.

All this kind of stuff. Obviously, you know, somebody’s working career that I, as the archivist, had to figure out what’s important, what’s not. There are certain situations where I might go in and say, we want it all, let’s box it up and move it to Fort Collins. There are other situations where I might say, I only want one or two things. I can tell what’s important, and we only want the gems. For this particular collection, since I wasn’t familiar with the person, I had done the research and I tried to figure out what work he did that was most important to him, to also influence the world of engineering, so to speak, as far as his consulting and his publishing.

Not that I figured everything out, but I was able to make some selections. I didn’t bring back everything. I left a good amount. But I did come back to Fort Collins — and I actually took two trips — came back to Fort Collins with something like 50 or 60 boxes of his materials. Of course, his wife, as she continues to clean out the basement there, she might call me up and say, “Patty, I’ve got some more. Would you be interested in this?” Or if she finds things she knows were important to his work, she can say, “Oh, you left this behind. You really should have this.”

To some extent, it’s a negotiation or collaboration with the donor and the archivist. Other times we do our research to the extent we can, but it’s also years of accumulated experience to help us know what we’re looking for, what’s important, what we don’t want to save.

Just so you know, some things that we don’t save or aren’t interested in might be publications. His shelves of books, shelves of government documents, not so interested in those kinds of things. If he or another donor might have lots of photographs or slides or those kinds of materials, and if they’re labeled, great. If we know what they are, that’s what we want.

If they’re not labeled, if they’re not dated, if we have no idea what they’re photos of or where the photos were taken or when they were taken, probably nobody else will be able to figure that out. Those kinds of unlabeled things, duplicate things, published materials are really things we are willing to leave behind. Because, yes, archivists are not packrats. We don’t want to save everything. We want to save what will be used by patrons, what is historically important to save.

What’s it like when you have that a-ha moment where you’re like — you stumble on a real gem and you’re like, oh, this, this is it.

Oh, that’s wonderful. I mean, there are times, especially since I’ve done this very subject-specific job for more than 20 years, that I can often instantly know if something’s important, if something is a gem. When it does happen, it is something that we can get excited about. We start making the plans of, well, let’s see how quickly we can make this accessible to the public. Let’s consider digitizing this right away and being able to put it online, because it’s not about us building collections for ourselves or for the institution. It’s about us finding those gems, those historically important things to make them available so that other people use them and are able to learn from them.

Speaking of gems, I know you have a few in that collection that have gotten a lot of love recently. From your perspective, what’s the one document that gets the most requests? I think I know the answer, but…

Well, the one document we’re often getting out or talking about is our copy of the Colorado River Compact. By our copy, I mean the copy that was owned by Delph Carpenter, who was a Greeley water lawyer, who was the person who originated the idea of interstate water compacts for the West. That’s something we get out often partly because of its significance, not only to the area and to Colorado, but to the West in general and really to the nation as a whole. It’s a really foundational document for how things operate, especially in terms of the Colorado River and other rivers in the West.

That said, there isn’t really one single document that the public or that researchers or patrons are requesting because we have such a diversity of materials and patrons have all kinds of really interesting research questions.

I will say a lot of locals and even CSU students tend to do research related to the Poudre River because it’s right here in our backyard, and we do have a number of Poudre River-related collections in the Water Resources Archive. Those are always fun. Those are always really interesting projects to dig into the rich history of the Poudre River, maybe with new perspectives or maybe telling the same historical story, but in a new way. But we do get all kinds of patrons with all kinds of questions. That’s part of the fun of archives, you never know what somebody’s going to want to look at or use, or what kinds of questions they will have that we have resources to help them with.

And the archive is accessible not just to students. Right?

Correct. Yes. Everything we have in the archives Special Collections Department at the library, which includes the Water Resources Archive, is accessible to everyone. We do have a few things that might be restricted for various reasons, such as attorney-client privilege or student information, things that might be restricted. But those are pretty few.

We are open three days a week for walk-ins over in Morgan Library, so people can come over and talk to us and request materials and use them there. We also are putting thousands of things online all the time, things that we’ve either digitized or materials that we’ve received digitally, and we’re putting those online so that people don’t have to come to Fort Collins if they’re not able to or don’t want to. That way, anybody around the world can use those materials.

Who typically comes to you looking for things? Is it students but also engineers? Who is coming in to look at the archives?

We have a wide variety of patrons, actually. Our patrons include scholars from other institutions. The Water Resource Archive does have a small fund where we award people funding. It’s called the Water Scholar Award, and people can apply for that and receive a small amount of funding to help them come to Fort Collins, if that’s what they need to do for their research.

We also get an occasional water lawyer who will be investigating something, likely for some sort of lawsuit or court case. We also get just the general public who might have questions about their new property that they bought, and a ditch going through or near their property that they’re curious about and want to know more about. So, our patrons are really unpredictable, but that’s what we’re here for, is to be open to everyone and help them with their questions.

As you mentioned, you’ve been in this role for quite a while. How has this role changed how you see water and its role in Colorado?

When I started this job, I knew about archives. I had archival experience in my background, but I was still new to Colorado, and I did not really know anything about water. I always say to people that easily, for the first two or three years in this position, I learned what I didn’t know about water, and I’ve been fortunate to be able to attend some classes here at CSU. I meet professors, talk with people, go to water conferences, and read a lot of books, of course, but really get a grasp of what water in Colorado means, what’s done, the current issues that are always evolving.

It’s been a real education for me to learn about water and how important it is, and think about things like, why are there so many water lawyers in the state of Colorado as opposed to elsewhere? Or what do we mean when we, you know, we talk about ditches a lot, and I’m originally from the eastern side of the United States. So, when I talk to relatives there and talk about ditches or ditch companies, I have to explain it’s about irrigation. It’s about getting water to grow crops. It’s not about getting rid of water, as ditches in the east are more about wastewater or getting rid of excess water. It’s been quite the education.

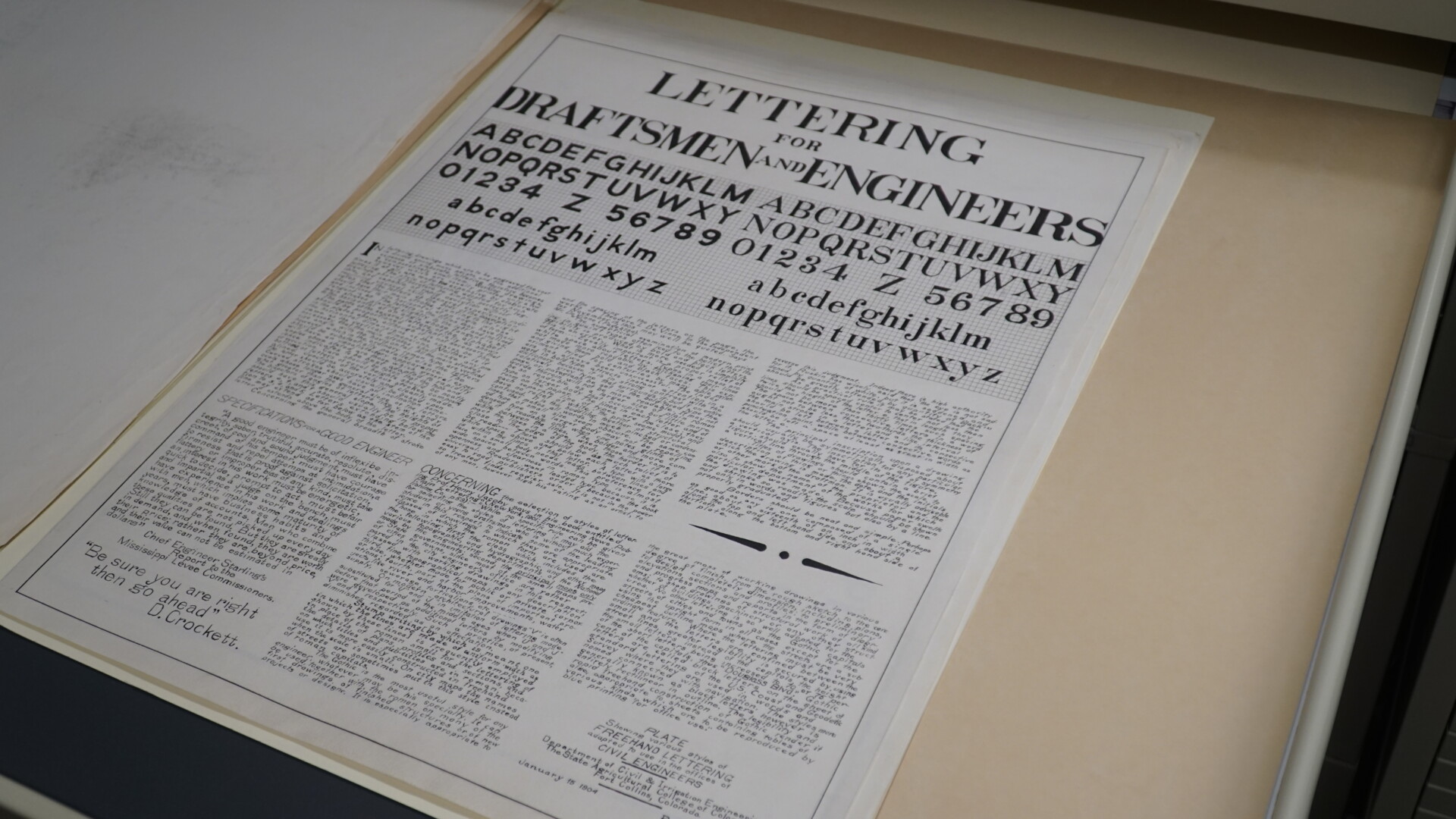

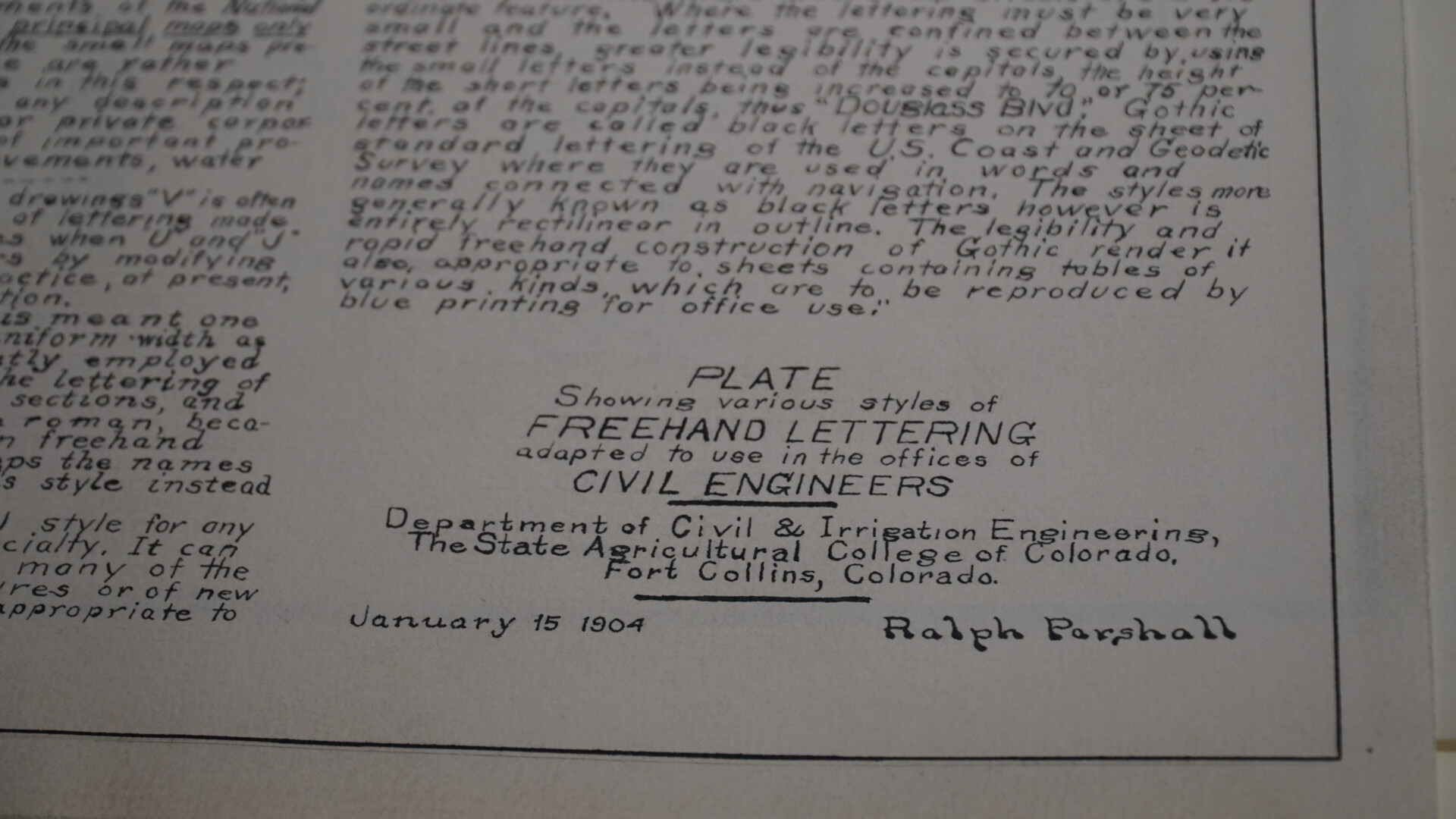

Earlier this week, I took a tour with you at the archive, and it was a little overwhelming to see such a variety of items, including from Ralph Parshall, who created the Parshall Flume. I learned about the Parshall Flume this week — a device developed to measure the flow of surface water and irrigation flow. You have some of his engineering homework from his time as a student at CSU, as well as a painting that he’d done later in life. Why are those types of things important to hold on to? What do they tell us about Colorado water history?

We talk about Ralph Parshall a lot in the Water Resources Archive, in part because of the importance of the work he did. You mentioned the Parshall Flume, that’s what we start with because it’s named for him, and it’s an innovation that had impact on water around the world. Ralph Parshall was a graduate of CSU back when it was Colorado Agricultural College in 1904 and had worldwide impact. His documents and the other kinds of things like that that we have in the Water Resources Archive are important because they help us know what’s happened before.

Since water is fundamental to all life, and here in Colorado what we do with water is absolutely fundamental, it really shapes how we are able to live here and what we are able to do here. It shapes our lifestyles in this state. What we’ve done with water, how we’ve moved it, how we share it or don’t share it, how we pollute or clean it up. What we do with the water has an impact on so many aspects of our lives. And knowing the history of who did what, what decisions got made, what was successful, what failures might have happened, what things were proposed that didn’t get done.

Knowing that kind of historical information helps us understand how we got to where we are today with some of our current issues. But it also helps us understand what we could do better or do differently going into the future. We can look at ideas from the past. We can look at those lessons and in the best case, apply them to develop a better future.

Thank you so much for being here, Patty.

It’s my pleasure. Thank you for having me.

That was Patty Rettig, archivist of CSU’s Water Resources Archive. I’m your host, Stacy Nick, and you’re listening to CSU’s The Audit.

SOURCE Special Report: Solving the water crisis

CSU has been at the forefront of hydrology for more than a century since Elwood Mead, the namesake of America’s largest reservoir, became the first head of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in 1883. This special report from SOURCE explores the research happening at CSU and provides insights into the ongoing water crisis across the country and around the globe.