What is subsidence?

CSU researchers use remote sensing to understand how groundwater pumping causes land to sink

Q&A by Josh Rhoten

published March 7, 2024

Approximately 77 billion gallons of groundwater are used each day around the globe for agriculture and human consumption. It is one of the largest sources of freshwater on Earth, but accessing the resource brings a unique set of considerations that do not exist for surface waters like rivers.

One of the main challenges in using groundwater is subsidence: the eventual sinking of land due to large of amounts extraction. Over time, that sinkage can increase flood risk, reduce underground water storage and damage existing infrastructure like roads. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, subsidence can happen anywhere in the world. But in the United States, an area roughly the size of New Hampshire and Vermont has been directly affected.

Assistant Professor Ryan Smith has been researching the issue for years as a part of his work in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. His team uses a variety of remote sensing tools, like satellites, to document changes from subsidence over time. The data they collect informs models that can help decision-makers plan for, understand and respond to changes from subsidence.

Smith sat down with SOURCE to discuss his recent published work focusing on changes from subsidence in California’s San Joaquin Valley and how the findings may help leaders there – and around the globe – address the issue in their planning.

What is groundwater subsidence? Is it always due to human activity?

Groundwater is water stored in small pores of sediments and rocks underground. We can’t see it, but there is a lot of it, and much more than all the world’s lakes and reservoirs combined. It supplies about a quarter of all water used in the United States. When water is stored in the porous space of soft sediments – like a sponge – it essentially is propping the layers up and prevents it from compacting down.

When we pump water out of the ground in areas that have lots of clay, the sediment loses that support and compacts. In some parts of the world, this causes the land to sink, and this is known as subsidence. Human pumping activity is the main reason this occurs, though it can also happen from natural processes. Subsidence increases flood risk, reduces aquifer storage and can cause billions of dollars of infrastructure damage to things like canals, railways and buildings. For the most part it is not reversible.

In the Central Valley of California, Mexico City and the North China Plain, the ground can sink as much as a foot in a year from pumping. We can see that change happen from space with a satellite technique known as interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR). The San Luis Valley is the only location in Colorado that is known to have experienced subsidence from groundwater pumping. In that region, the ground is sinking much less: up to a third of an inch per year.

You recently published findings describing how different regions in California have experienced subsidence over time. What does your paper discuss?

The San Joaquin Valley has all the ingredients needed for subsidence – large amounts of clay, pressurized subsurface water that supports the clay and high volumes of groundwater pumping that dramatically reduces the ability of the clay to hold up the ground above it. That combination has led to it subsiding a lot – up to a foot per year – making it a great laboratory for understanding the phenomenon.

Our paper shows how a history of extensive pumping in one region led to significant subsidence but also made that area less susceptible to the phenomenon during recent droughts than a neighboring area. However, we found that if groundwater depletion continues there, subsidence in both regions will likely be substantial in the future. Our work resulted in a model that can predict those changes based on water use and recharge scenarios and could be a valuable tool for active management.

How does the paper fit into your larger research activities? What questions are you looking forward to studying in the future?

We are interested in leveraging the massive satellite datasets available to better understand groundwater systems. One area in particular that I am interested in is how we can better integrate InSAR data into groundwater models. Those models have tons of uncertainty, but if we can continue to improve them, they would be very useful at a policy level for deciding how much water a given region should be able to pump and use. There has not been much work on that to date, and being able to incorporate subsidence into the models could greatly improve their accuracy. We have an ongoing National Science Foundation Award that will explore that topic further.

SOURCE Special Report: Solving the water crisis

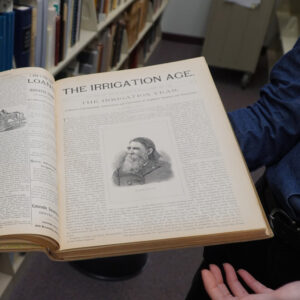

CSU has been at the forefront of hydrology for more than a century since Elwood Mead, the namesake of America’s largest reservoir, became the first head of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in 1883. This special report from SOURCE explores the research happening at CSU and provides insights into the ongoing water crisis across the country and around the globe.