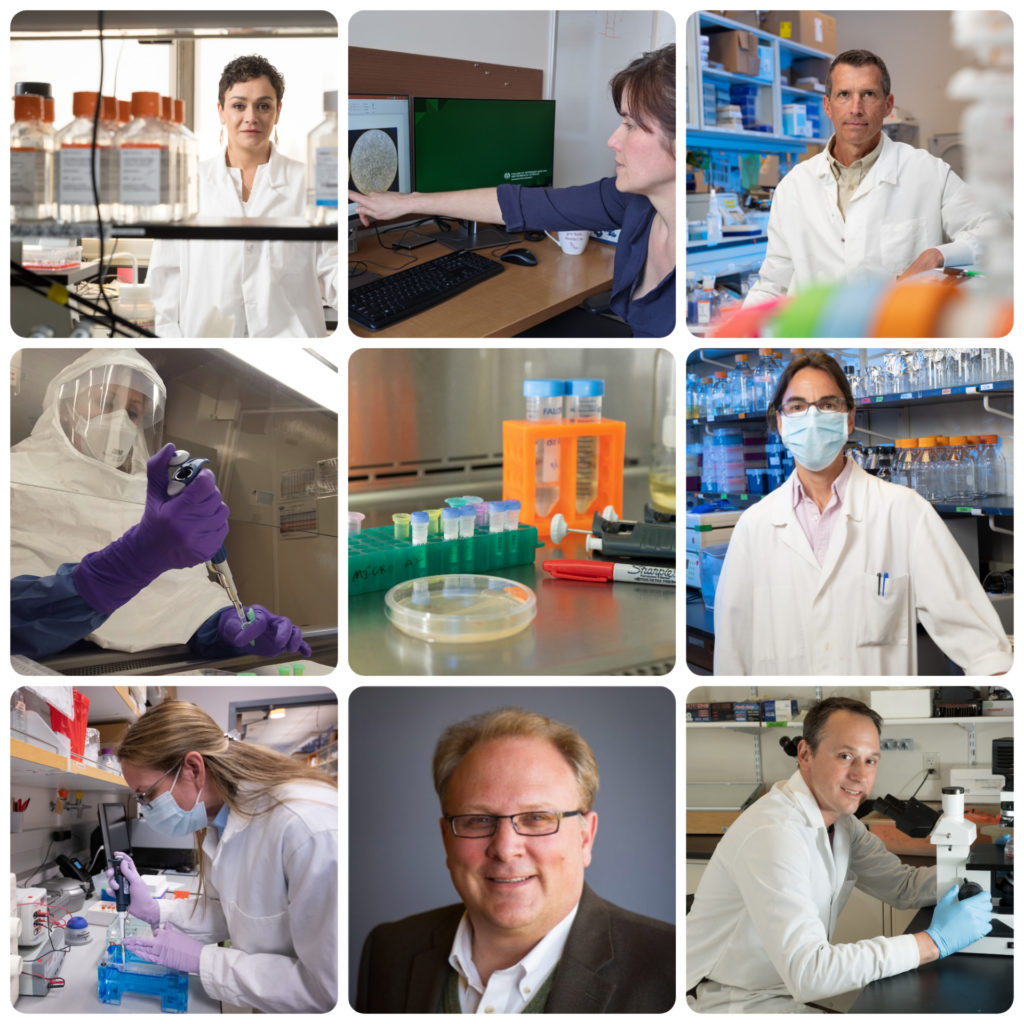

Top row: Dr. Marcela Henao-Tamayo, Lindsay Hartson, Dr. Gregg Dean; Middle: Dr. Izabela Ragan, Mary Jackson; Bottom: Dr. Amy MacNeill, Ray Goodrich, Greg Ebel Photos: CSU Photography, Rae Ellen Bichell / KUNC & Mountain West News Bureau

As scientists at Colorado State University continue their research on four coronavirus vaccine candidates, investigators are developing a plan to collaborate with scientists at other universities to create a pan-coronavirus vaccine that could help in future pandemics.

Researchers complement each other’s strengths

Ray Goodrich, director of the Infectious Disease Research Center at CSU and lead investigator of the SolaVAX™ vaccine candidate, said that work from his team is progressing well.

SolaVAX™ uses UV light and riboflavin to create an inactivated virus, which stimulates a person’s immune system to fight the virus. To produce this vaccine candidate, researchers have repurposed a commercial platform that is currently used to inactivate pathogens in blood transfusions. Goodrich was one of the creators of this commercial platform.

“We have completed a second round of vaccine challenge study work, essentially testing to see if the vaccine works in an animal model,” he said. The team is also examining the persistence of antibodies following vaccination.

Dr. Marcela Henao-Tamayo, a member of the research team and an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Pathology at CSU, said the university’s researchers – who come from different research backgrounds – complement each other’s knowledge.

“Our aim is to be ahead of infectious diseases that are impacting the world, instead of playing catch up,” she said.

Henao-Tamayo said excitement is building for a possible coronavirus vaccine that could help in years to come.

“We’re seeing an investment from the federal government to protect against a possible virus that we know is coming, based on what we’re experiencing,” she said. “We have a lot of different ideas on how to approach creating a pan-coronavirus vaccine and we will work together to find the best combination of approaches.”

One vaccine candidate progressing to human clinical trials

Goodrich and his team were awarded a base contract worth $3.1 million from the National Institutes of Health in September 2020, and have been in discussions with NIH about what comes next to progress to human studies.

“So far, everything seems to be going extremely well,” he said.

Goodrich said the team never expected SolaVAX™ would be among the first vaccines approved for the public to help put an end to the current pandemic. But the team and others – including federal agencies – recognized their work may be relevant down the road.

CSU received $699,994 from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) to develop this novel coronavirus inactivation process in June 2020. The university contributed $448,143 to support this project, bringing the total contribution for this phase of the research to $1.15 million.

“How we are making the vaccine and the potential to scale it up shows promise,” he said. “Making some of these vaccines in a large quantity is a challenge, as people have seen. That’s an area where our approach might be able to help.”

Although two coronavirus vaccines are currently in use, Lindsay Hartson, lab manager at the Infectious Disease Research Center, noted that research must continue to keep pace with the evolving virus.

“As we have observed this virus evolve and new variants emerge, we should celebrate the fact that while we have two vaccines already being administered to people in the United States, our work is not done yet,” she said. “Our vaccine approach still has a great deal of value, given the way this virus is behaving and continues to challenge our efforts to combat its spread worldwide.”

Second vaccine candidate draws interest from industry

Dr. Gregg Dean, a veterinary scientist and head of the Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Pathology at CSU, is pursuing a vaccine that uses a genetically modified form of the probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus, a bacterium commonly found in yogurt and other foods for gut health.

He and his team recently completed their first preclinical study, and Dean said the results were very promising. In late 2019, Dean received a $3.5 million grant from NIH to work on a vaccine against human rotavirus, a family of pathogens distinct from coronaviruses that also attack the mucous membrane.

He had also pursued a vaccine against feline coronavirus in research supported by the Morris Animal Foundation. When the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, Dean’s research team immediately pivoted to working on a human coronavirus vaccine.

“We don’t know yet whether the vaccine candidate is protective, but the findings are parallel with what scientists have found in humans in terms of how the immune system responds to a vaccine,” he said.

The results are favorable enough that Dean is actively working with several companies that are interested in acquiring the technology.

“We knew we wouldn’t be in this first wave of vaccines produced for COVID-19,” he said. “But what we’re seeing in the U.S., with problems distributing a vaccine even once it’s ready for use in human patients, we believe our approach still has potential.”

Just last month, a freezer failure at a medical center in Seattle led to an emergency call overnight to the community, so that clinicians could distribute some 1,600 doses of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine.

“Storing the existing vaccines requires the infrastructure to do that,” said Dean. “There’s also the fact that two immunizations are required. Lastly, they’re not that easy to manufacture and distribute, and they cost a fair amount of money.”

Dean said when considering the need to vaccinate people around the world, those concerns are real obstacles, and they don’t exist for the vaccine candidate his team is developing.

“I hope we can continue to move it along, prove it to be efficacious,” he said. “We’ll keep working on it. We also know now that the coronavirus isn’t something that is going to go away.”

New vaccine work to address future pandemics

Dean is also overseeing plans to create a vaccine candidate that would protect people from a spectrum of coronaviruses, in collaboration with scientists from North Carolina State University, West Virginia University and University of California Irvine.

“Everybody had a gigantic wakeup call that a virus can emerge from animals and become a pandemic,” said Dean. “We’ve talked about it for years and there were plenty of people that worked to prepare for it and prevent it, but here we are. We don’t know what’s emerging right now and we have to be better prepared going forward.”

The team will submit its plan to the NIH, which has issued a call for proposals. Dean said the CSU team will use existing approaches to create this new vaccine, including the SolaVAX™ method, lactobacillus platform, and an approach led by Professor Mary Jackson, who is using a process similar to how the vaccine to prevent tuberculosis was created in the early 1900s.

Professor Greg Ebel, director of the Center for Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases at CSU, is one of the leads on this new coronavirus vaccine project. He and his team have been studying the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 over the last year, using data from research conducted in skilled nursing facilities in Colorado. SARS-CoV-2 is the virus that causes COVID-19.

“We’ve recently seen new variants of the virus and they are more transmissible,” said Ebel. “That is concerning because it’s changed how we view the evolutionary process of this virus.”

Ebel said questions that remain about the virus include: What if a person is vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 and they’re exposed to SARS-CoV-1 or an older virus? He and his team are using computational models to try to predict what will happen with older and existing viruses.

“We want to prevent viruses from emerging that are really dangerous by designing vaccines so that the virus has to essentially fall on its sword and mutate in ways that will make it less virulent or non-existent,” he said.

Researchers optimistic about impact, future of projects

Dr. Izabela Ragan, postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Biomedical Sciences at CSU and a member of the SolaVAX™ team, said the research completed so far provides more than just another weapon to fight SARS-CoV-2.

“Our work has revealed key data on the infectivity of this virus as well the immune response,” she said. “We hope our work will have a significant impact on this pandemic and offer countermeasures for other emerging pathogens.”

Goodrich said it’s been incredible to watch the swift development and approval of existing vaccines to fight the coronavirus.

“It really demonstrates to me what can be done when you have people with many different talents, backgrounds and perspectives working to solve a problem,” he said. “In a difficult and trying time, this has been an example of hope and how science can be used to advance humanity. It’s very rewarding to see it happen and be a part of it.”

Henao-Tamayo said that being a scientist during the pandemic – with the hope of creating a therapeutic or preventive vaccine – has been a real learning process.

“The disease can cause so many different conditions, and we see people and patients suffering so many debilitating conditions,” she said. “There’s also still many things that researchers and clinicians do not understand about the virus.”