When it comes to wildfires,

history isn’t as useful as it used to be

q&a by Stacy Nick

published July 31, 2023

Colorado State University Professor Jason Sibold is a geographer with research focused on interpreting the natural and anthropogenic drivers of forest ecosystem changes to aid forest management, restoration and conservation.

His research uses a combination of techniques that focus on wildfire impacts of the past, including dendroecological (or tree ring) analysis, but also mapping current conditions with a combination of field data, Geographic Information System (GIS), remote sensing and spatial analysis to aid in predicting future outcomes.

But it wasn’t always that way.

“All of my training was in looking back into the past using tree rings for the past 400 or 500 years in the western U.S.,” Sibold said. “When I got to CSU in fall 2008, I wanted to be extremely applied in my research and help ecosystem managers and conservation groups address problems. As a land-grant university, CSU was a perfect fit for that. But I started to realize that looking back and providing managers and conservation groups and other scientists and policymakers with this foundation of what’s happened in the last 400 or 500 years was starting to lose its value. As I tell students, the past isn’t what it used to be. It’s not as valuable as it once was.”

That’s not to say historical data isn’t valuable, he added. But with every year showing increasingly dramatic and record-breaking climate shifts, it’s becoming more difficult to use the past to gauge the future.

SOURCE recently talked with Sibold to find out more.

When did this shift in the fire regime occur?

We weren’t good at stopping fires or altering patterns of fire until the 1950s. Then in about the year 2000, we stopped having that command and control over the process of wildfire, that ability to dictate when and where it happens, how big it is and how severe it is throughout the Western U.S. and now, globally.

Climate change is accelerating other disturbance types, not just the ecological disturbances that are driven by dry, hot conditions like beetle outbreaks and drought mortality and wildfires, but we’re also seeing wet extremes creating exceptional flood events and avalanche cycles. We’re on this crazy pendulum — while our weather is swinging further and further to the hot and dry side of things since 2000, there are some swings back to the extreme wet side as well.

What kinds of impacts are you seeing right now?

The big thing we’re seeing is that there’s a lot of ecological disturbance happening — beetles; blowdown; drought mortality in our Aspen forests; wildfires. Wildfires get people’s attention, but there are many slower moving, not-as-obvious disturbances that you don’t have to flee from that don’t make the evening news. Because of these accelerated rates of all kinds of ecological disturbance, we see more interactions between events. For instance, two fires in a brief period of time, or beetles or drought mortality followed by fire. And we see that a lot of these forests just cannot come back from combinations of severe events. Moreover, they are trying to recover under warmer and drier conditions.

But that is not true for all forests. Spruce-fir forests are having a much harder time recovering in a warmer world following fire and combinations of disturbance a — think beetle outbreak followed by wildfire. Lodgepole pine forests however are generally able to come back though, even in the context of combined beetle, wildfire and drought. Lodgepole pine are just much better adapted to fire as well as recent climate conditions. Overall, we’re seeing a lot of change.

How are all these ecological disturbances impacting forest adaptation?

Well, it’s not all bad. For one, ecological disturbance is a great way to promote biodiversity. It creates different habitat types for insects, birds and mammals. Ecological disturbances are great for ecosystems, overall. And in the context of the rapid warming that we’ve seen in the last 20 years and that we’re anticipating seeing in the next 100 years, ecological disturbance will likely play a central role in ecosystem adaptation.

Disturbances open sites up, like hitting the reset button of our landscapes. A wildfire cleans the slate. It allows species to start moving around and adjust to the new climate we are in and that we’re moving towards.

It sounds like a little bit of a silver lining to climate change?

Yes, we need events like extreme drought or beetles or fire to open up sites, because as long as established forests are intact, they will hinder the ability of other species to move around and specifically to move up slope to track the climate conditions that they need to survive. In other words, disturbances like fire will clear away existing forests that are no longer adapted to current and projected climate and open the site for species that are better adapted to these new climate conditions to migrate into the site. It is also possible that in some cases we may see the same species as before but perhaps not at the same densities or maybe mixed with new species.

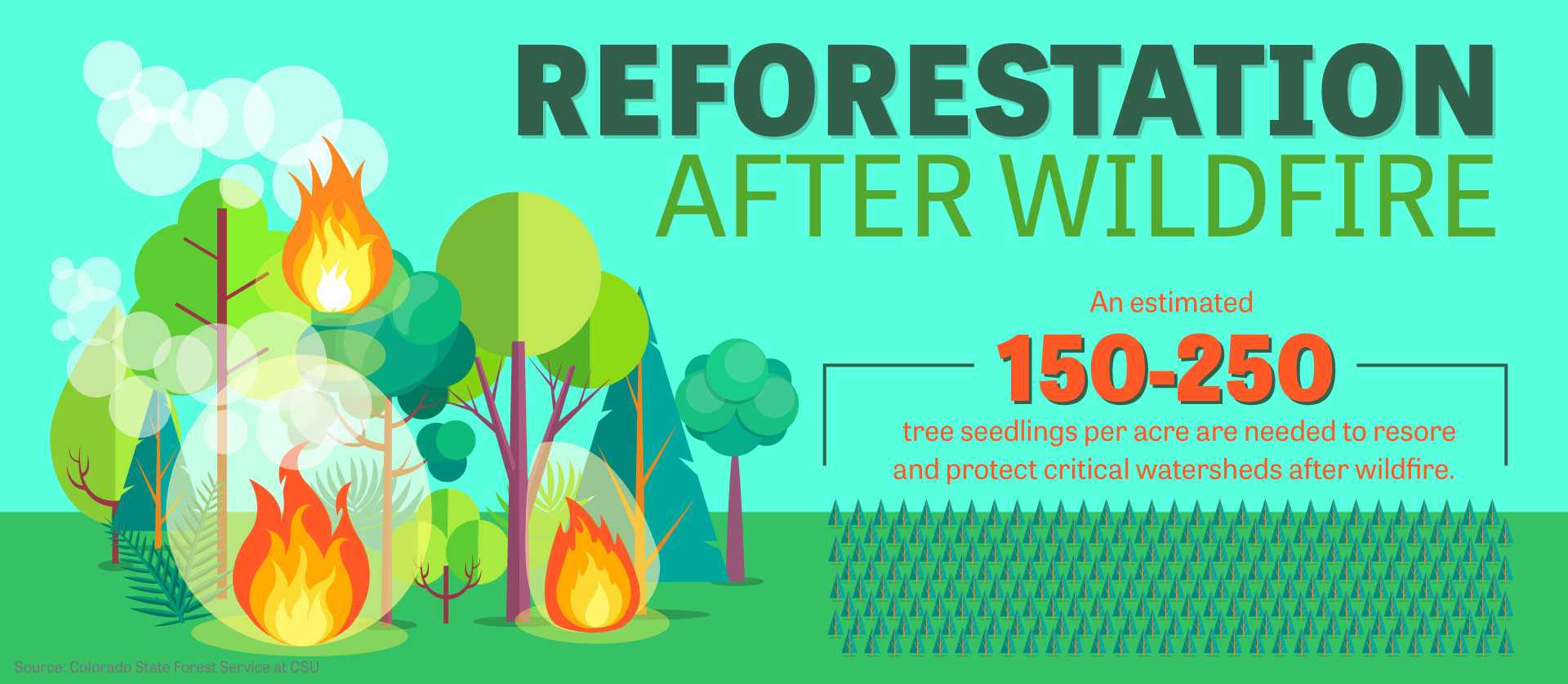

Infographic by Kerry Fannon/CSU Communications

One research area you focus on is the interaction between insects and wildfire. What are some of the implications of this work?

For one thing, the rapid warming starting in about 2000 has resulted in extensive beetle outbreaks — hundreds of thousands of acres of beetle-killed forests. This means that fires are highly likely to burn in beetle-killed forests and understanding these interactions applies to extensive areas of Colorado.

What we see is that fires in beetle-killed forests are different in several ways. Beetle outbreaks are not causing the significant uptick in wildfire, extreme fire weather conditions are the driver of increasing wildfire, but beetle-kill forests still have an influence.

In spruce-fir forests we have found that the severity of fire is much higher in areas with higher severity pre-fire beetle outbreak. In other words, stands where nearly all of the trees were killed by beetles before the fire, which is true for a lot of the beetle outbreaks in our higher-elevation forests (“subalpine forests” above about 9,500-10,000 feet), fire intensity at the soil level is higher than in areas without high-severity beetle outbreak before the fire.

These higher-severity burns are making it much harder for spruce or even grasses and shrubs to get established in these burn areas. One of the main reasons is because the severity of the burn is amplifying our warming conditions — high-severity burn areas are much warmer than forests that did not burn at as high of severity.

Interestingly, other species that are better adapted to wildfire, like lodgepole pine, are not really having an issue with the double whammy of beetles and wildfire. They are, however, having a really challenging time with two fires in short succession, which we are starting to see more and more. For example, the East Troublesome fire in 2020 burned over some areas that had burned just seven or eight years earlier. We don’t see lodgepole pine in those areas — these were areas that in the past only burned every 150 to 300 years, so dropping to less than 10 years for a fire interval is outside of their ability to come back. In both cases of interactions that are pushing species past their ability to recover, we are often seeing a shift to a grass and shrub dominated landscape and, in some cases, aspen forests are moving in — perhaps an indication of the systems adapting to our warming climate.