Colorado State University faculty members Reza Nazemi, Yan “Vivian” Li and John Mizia earned 2023 grants awarded by Colorado’s Advanced Industries. Two projects focus on turning agricultural waste into reusable material. The third strives to develop an LED photochemical vaccine manufacturing testbed.

This is the first of three stories about the researchers and their projects:

The researcher

Reza Nazemi, assistant professor of mechanical engineering, earned a $150,000 grant. He has nine people working in his lab at CSU’s Powerhouse and plans to hire two more.

The research

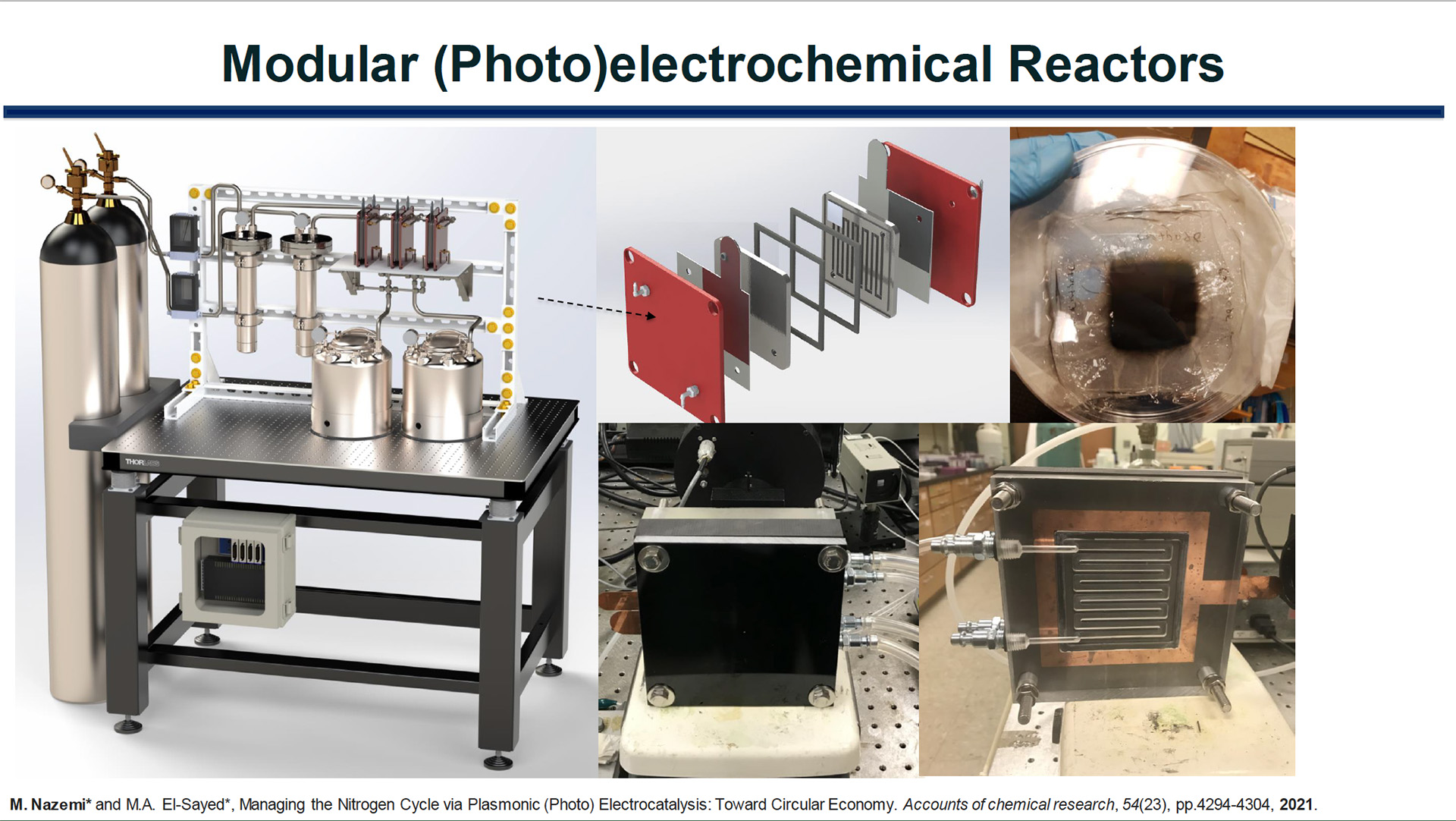

Developing modular electrochemical systems powered by renewable electricity to produce nitrogen-based fertilizers from agricultural waste streams.

The idea

Nazemi’s research aims to build a field-side reactor to capture fertilizers from runoff that can be re-used, promoting a circular economy and limiting chemicals from getting into water sources.

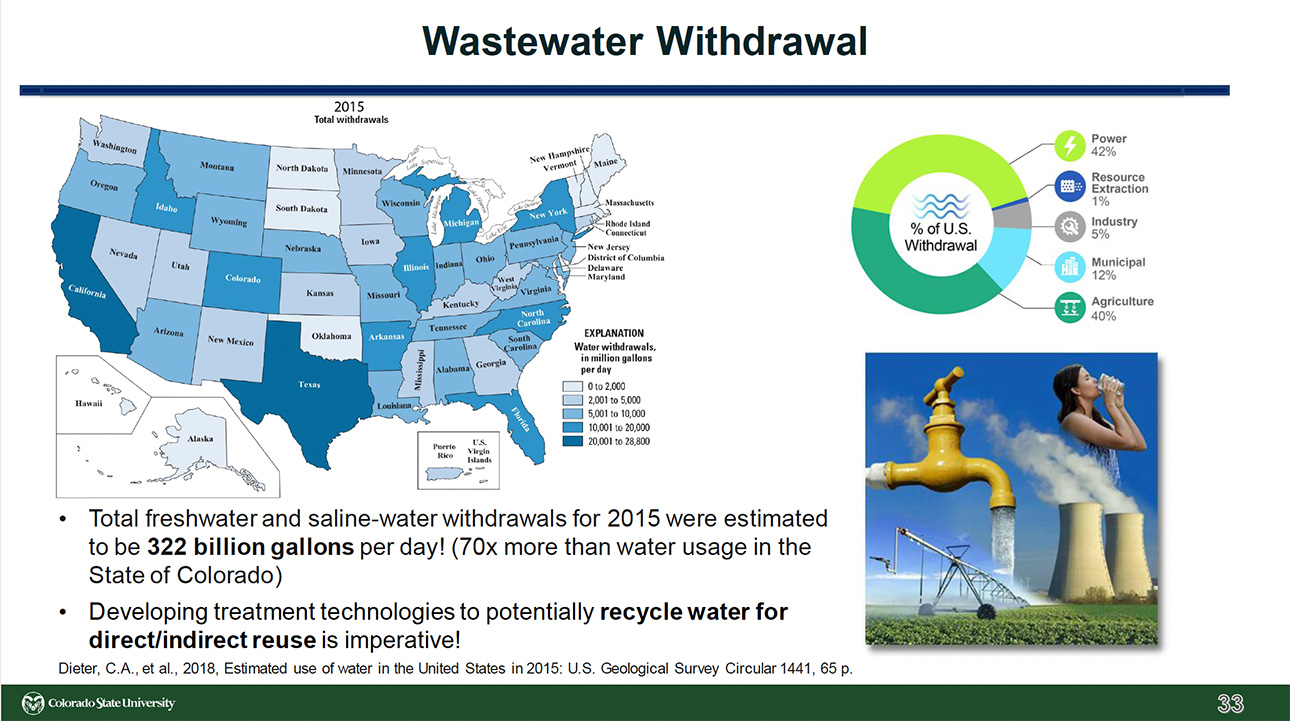

“Especially in the developed countries like in the United States, we have overuse of fertilizers. Once you use irrigation, those fertilizers have runoff because the plant has a limited capacity to take those fertilizers,” Nazemi said.

“Then it runs into streams or groundwater or surface water, and that basically contaminates our water streams. So, the idea is developing these models of a system to take that runoff basis and convert it to some value. … Trash to treasure. I think that’s the idea.”

National Environmental Protection Agency studies confirm that agricultural runoff is the top source of pollutants in studied rivers and lakes.

How it works

How it works

Nazemi explained this science this way: “Our electrochemical system is composed of an anode (positive terminal) and a cathode (negative terminal) that are separated by a polymer membrane but ionically connected. A cathode is made of a proprietary catalyst coated on a conductive support to facilitate the transformation rate.

“The nitrogen source (fertilizer runoff), water, and in some cases, carbon dioxide will react at the cathode near the catalyst surface to produce the desired nitrogen-based fertilizers. The process leverages an electric field generated by renewable electricity instead of the heat and pressure traditionally used by industry to make these chemicals.”

Transportation impact

“These modular electrochemical systems can be right across from the field. Farmers are really excited right now because you don’t have to transport your own fertilizers,” Nazemi said. “You don’t have to store your fertilizers, and you just base it on demand and fit it to your purpose. You can easily switch it on and off and run your own system.”

Powering the system

“If you’re living in Colorado or Wyoming, maybe wind is the viable option here. If you’re living in Nevada or Arizona, maybe solar. In some places maybe it’s nuclear or hydro.

“I’m very interested in renewable fuels, how we can transition from a carbon-based economy to a net-zero carbon economy. And right now, there is a huge focus on utilizing hydrogen, the fuel for the future. But at the same time, you need to expand that capacity to hydrogen-based fuels like ammonia, methanol and those hydrogen carriers.”

Scaling up

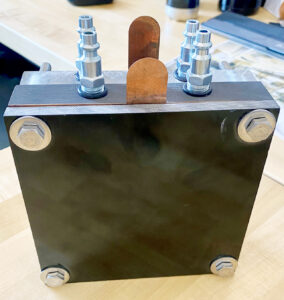

Nazemi has a small prototype of the device in his office, but one day he said a commercial machine would be about half the size of his office.

“The plan is if you’re looking, for example, at a corn farm in Iowa, a 1,000-acre farm requires about 50 metric tons of nitrogen-based fertilizer. Our system is capable to meet that demand, to meet that footprint.”

To get to capacity, the system must get more proficient. “We put a proposal of $4 million from the Department of Energy, and we are 100 times below the scale that this should be for basically to get to the commercial size,” Nazemi said. “Maybe you’re thinking that’s huge. But we can easily get to that hundred-times factor.”

Business angle

Nazemi said a key factor for farmers will be being able to afford the electrochemical system. “Right now, we’re at two years (to get a return on the investment), but I’m hoping to improve the system to get it to potentially one year, but at 1.5 years a farmer can get to the break-even point. After that, you’re just making a profit.”