When the COVID-19 pandemic suddenly forced us to spend a lot more time at home, many people became amateur breadmakers, recording countless videos of their own gooey, bubbling sourdough starters along the way.

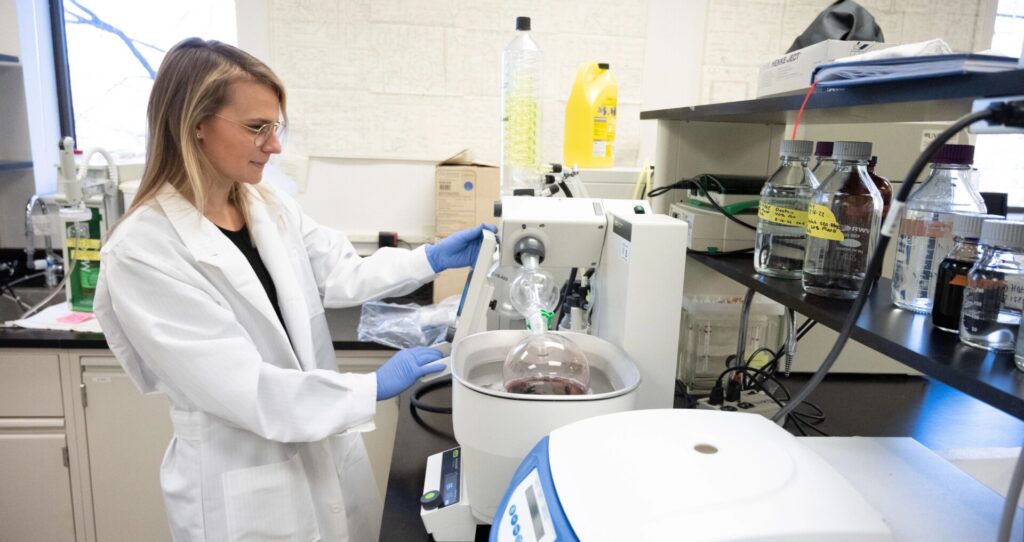

And while many of those videos might look the same, at a microscopic level, no two versions of the sourdough starters that live in kitchens around the world are exactly alike – an idea that has exciting implications for scientists like Charlene Van Buiten, an assistant professor in the Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition at Colorado State University.

Van Buiten’s USDA-funded research focuses on how different combinations of bacteria and yeast in sourdough can yield different health benefits, ranging from a reduction in gluten to the ability to make bread without the synthetic additives found in other products.

“Our latest study focuses on how different groups of organisms can affect quality in bread, including things like texture and color,” Van Buiten said. “This demonstrated that we can see vastly different outcomes based on the starter culture that’s being used.”

These findings were highlighted in a recent paper in the Journal of Food Science, where Van Buiten collaborated with fellow food scientist Josephine Wee (Pennsylvania State University) and microbial ecologist Benjamin Wolfe (Tufts University) to study the connections between different sourdough starter microbiomes and ensuing bread quality to begin to understand how these factors could allow for the targeted development of products with specific physical and chemical properties.

“If we can use this information to create products that are sustainable and successful and don’t have additives, I think this can have a really profound impact on the food industry and consumers alike,” Van Buiten said.

Breaking down the molecular composition of bread

For the initial rounds of the study, members of Van Buiten’s Food Structure and Function Laboratory fermented and baked 60 loaves of bread using 20 unique sourdough starters that they received from Tufts University.

They analyzed the impact of each starter’s microbial profile on basic bread quality, including acidity, crust color and texture. These breads will next be used to determine how different bacteria and yeast combinations impact gluten content and the chemical metabolites produced in the bread. Metabolomic analysis is being completed in collaboration with Jessica Prenni, a professor in the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture at CSU, as part of the Periodic Table of Food Initiative.

“Our team looks at the molecular composition of the dough and bread, and finds patterns and differences in the compositions that correlate with the specific bacteria in these sourdough starters,” Prenni said. “The idea is that we might be able to identify some specific health-promoting molecules that are generated through one culture and not another.”

The next phase of Van Buiten’s research will look at whether certain sourdough starters will be able to break down gluten – a mechanism that could have big benefits for the estimated 7% of people from around the world with an intolerance to this common bread protein.

“Over my years as a celiac disease researcher, I’ve heard plenty of anecdotal stories from people who claim to have gluten sensitivities, but still eat sourdough,” Van Buiten said. “There currently isn’t any concrete data supporting this, but other researchers have identified microorganisms in sourdough starter cultures that are able to break down gluten to the extent that it doesn’t trigger an inflammatory response in gluten-sensitive individuals. What we don’t know is whether these effects can be observed outside of a laboratory, in a setting that aligns more with industrial bread production.”

And, if researchers like Van Buiten and Prenni can determine which combinations of bacteria and yeast are able to reduce gluten content, they could help businesses create products that utilize these ingredients to their advantage.

“Once we know how the mechanism works, we can start to intentionally design or engineer the sourdough starters to have the outcomes we want,” Prenni said.

The Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition is part of CSU’s College of Health and Human Sciences.