Global climate change has made the future of the Arctic region uncertain.

Colorado State University researcher and instructor Pat Keys says that the possible futures could be positive, negative or somewhere in between.

Keys, the lead scientist for the School of Global Environmental Sustainability, said he may be the first to combine computational text analysis to gather themes about the Arctic and then use a story-based scenario process to write 10 short science fiction stories.

Keys said “futuring” of the Arctic has been done for decades.

“The Arctic is a place that is changing faster than almost anywhere else on the planet in terms of climate change,” said Keys, adding that the region has long been characterized in scenarios by fossil fuel companies and for its cultural, ecological and governmental diversities. “It’s changing before our eyes.”

Paper to be published

Keys’ research paper was accepted for publication in Earth’s Future. Keys will speak from 3-4 p.m. today about “Creating Sustainable Futures: Adventures in Story-based Scenario Design” in the Warner Natural Sciences in NATRS 113.

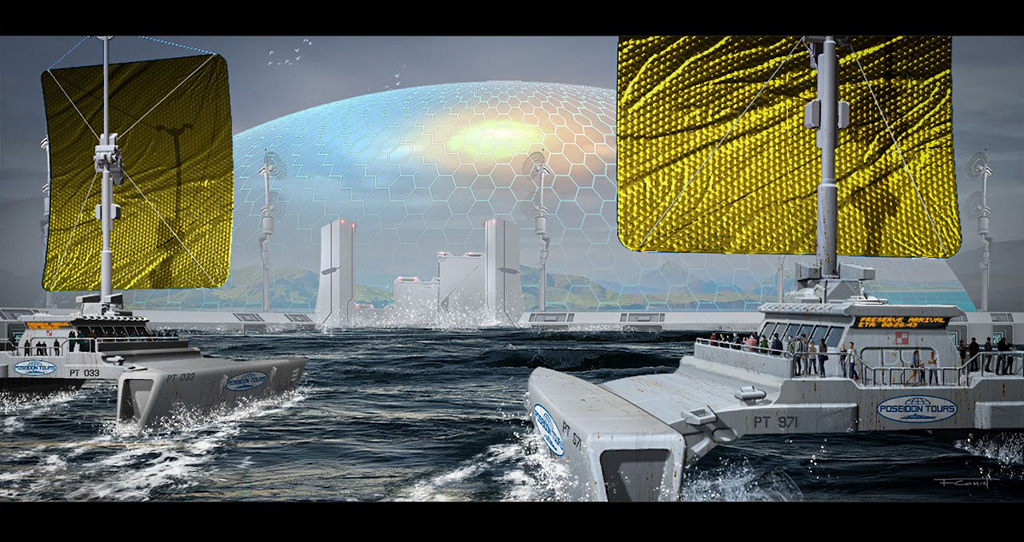

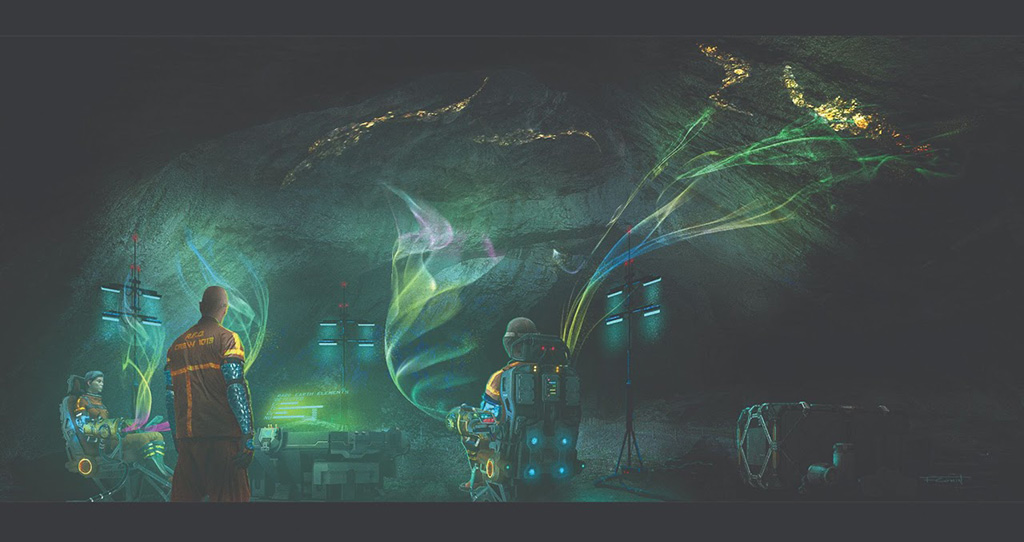

In his abstract, Keys wrote that “story-based scenarios can provide vital texture toward understanding the myriad possible Arctic futures.” Artist Fabio Comin designed illustrations for each story.

Keys said one story, “Icebreaker,” is set in a militaristic future off the coast of Russia. “Nanook Station” takes readers inside a top-secret neural lacing program for polar bears.

In “Security Detail,” China has become the world’s preeminent superpower and used thawing Arctic waterways to create more shipping routes and build Arctic ports. But there also seems to be some agreement on ways to preserve wildlife.

Keys said “Campus Utqiaġvik” and “Assisted Migration” are positive examples of humans adapting to changing circumstances. “It’s a whole range,” Keys said. “It’s a pretty diverse set, thematically.”

The process

Keys said his team took a decade of English-written news stories and opinion pieces – more than 2,000 in all – and ran a computational text analysis that identified 10 patterns of keywords. Those 10 themes were crafted into stories.

“I didn’t want to necessarily exclude opinion, in part because the whole point of this was, ‘What are people talking about regarding the future in the Arctic?.’ A lot of that is opinion, and that is OK,” Keys said. “What I wanted to do in this project is take something that was very quantative – this computational text analysis – and see if we could take the output, that is those themes and topics, and use those as the starting point for something very creative.”

Keys and his then-undergraduate assistant, Alexis Meyer, authored the stories using a story-based scenario and science fiction prototyping. A video describes the process.

“My futures colleagues like it,” Keys said. “My (computational text analysis) non-futures colleagues are like, ‘What are you doing?’ Those two groups of people almost never mix. And so, one thing that I think this does is that it helps provide a conversation piece that links two communities, two disciplines, two groups of people that are thinking about the future, that do not rub shoulders very often.”

Perspectives

Meyer originally was to be involved only in the computational analysis portion.

“Once that work was completed and I was invited to participate in the creative, story-based aspect of the project, my perspective completely changed,” Meyer said. “There was a switch from an analytical mindset to a creative one. When I first started the story-writing process, I was unclear how these tales would engage an audience to make change – until I was writing my own and thinking of backstories and the history that had to unravel for us to move from our present-day society to my storyline. It made me question my daily choices and how they may have an impact on preventing or providing for a certain story to come to life.”

Leeann Sullivan invited Keys to speak to the Colby College (Waterville, Maine) environmental studies students during their 50th anniversary and what their program may look like in 50 years.

“Pat’s project was perfect for framing this discussion, as it not only asks these same questions but really brings them to life in a way that science is limited in its capacity to do,” Sullivan said. “It was not just a summary of the data – it was an application of data to thinking about the worlds we could inhabit. I particularly like that it was not prescriptive or pessimistic.”

‘Don’t Look Up,’ look ahead

It is often said that every disaster movie begins with someone not believing a scientist. Netflix’s Don’t Look Up film uses a “planet-killer” meteor hurtling toward earth as an analogy for climate change.

Meyer liked Don’t Look Up and applauded A-list actors being used to draw eyes to a movie, even if a cause-and-effect cautionary tale is a simplistic way to communicate science. She said the far-fetched ideas in Arctic Stories may not be any wilder as a Zoom call would seem 50 years ago.

Keys said people can imagine how their own actions affect the future or, better yet, they could write them. “They’ve seen a disaster movie or something, but they’ve never written a story,” he said. “They’ve never imagined it from the ground up themselves.”

Sullivan said the downfall of movies like Don’t Look Up is that, unlike entertainment, the real climate problem is “a complex, socially embedded problem that will require fundamental changes to everything about how we organize our lives on this planet.”

She added that painting the future could take many forms and there should be room for “creating an opening for discussion around what we want the future to look like and how we build that together.”