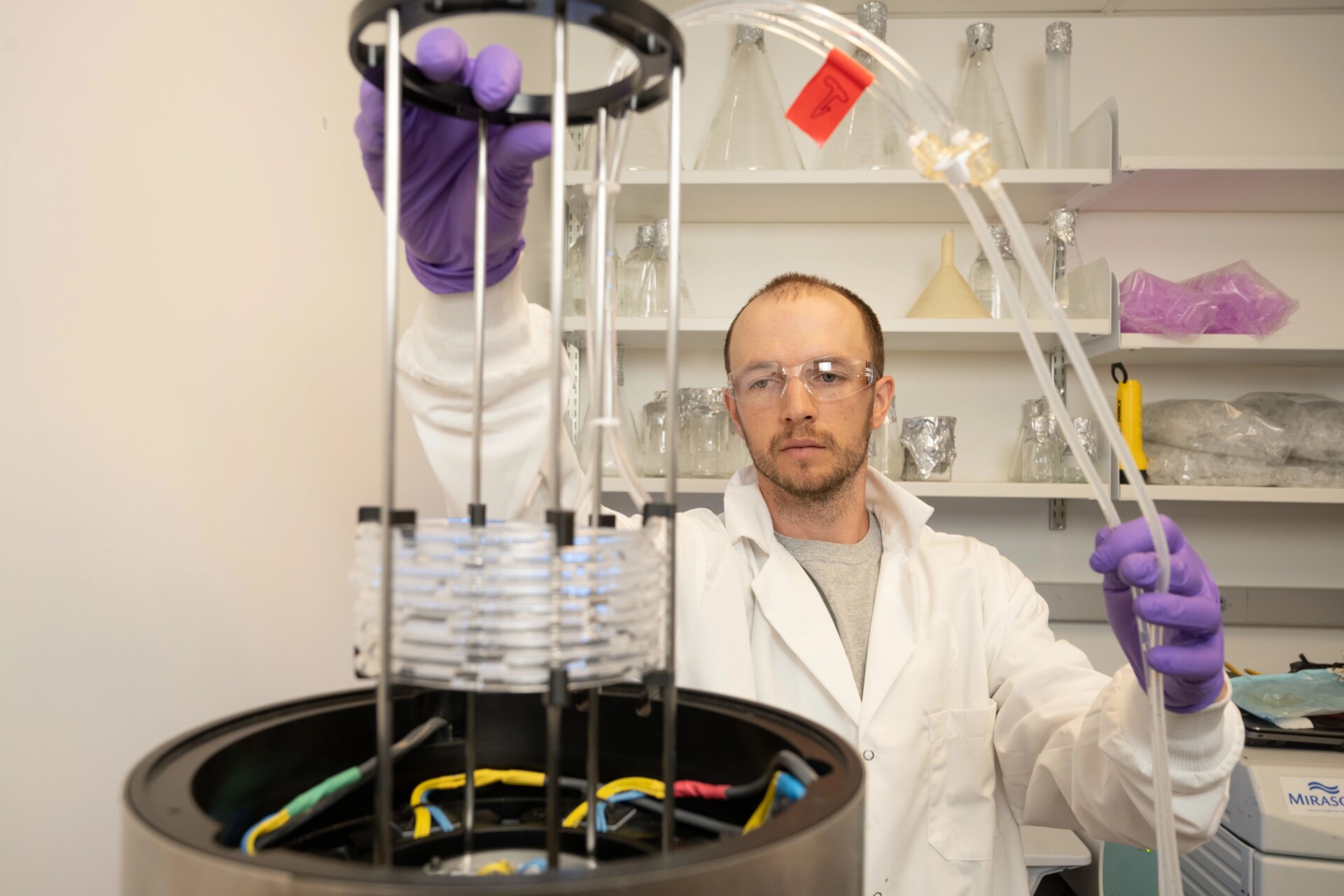

Andrew Andraski, a master’s student in the Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering, uses Zika virus to test the VacciRAPTOR (Vaccine Production for the Rapid Response Technical/Operations/Research Teams) machine, which uses UV light and riboflavin to kill pathogens. Photo by John Eisele

Three Colorado State University faculty members were among 43 private-sector and academic researchers awarded grants to pursue ground-breaking innovations in technology, biotech and key industries.

CSU’s Reza Nazemi, Yan “Vivian” Li and John Mizia earned 2023 grants awarded by Colorado’s Advanced Industries. Two projects focus on turning agricultural waste into reusable material. The third strives to develop an LED photochemical vaccine manufacturing testbed.

This is the third of three stories about the researchers and their projects:

The researcher

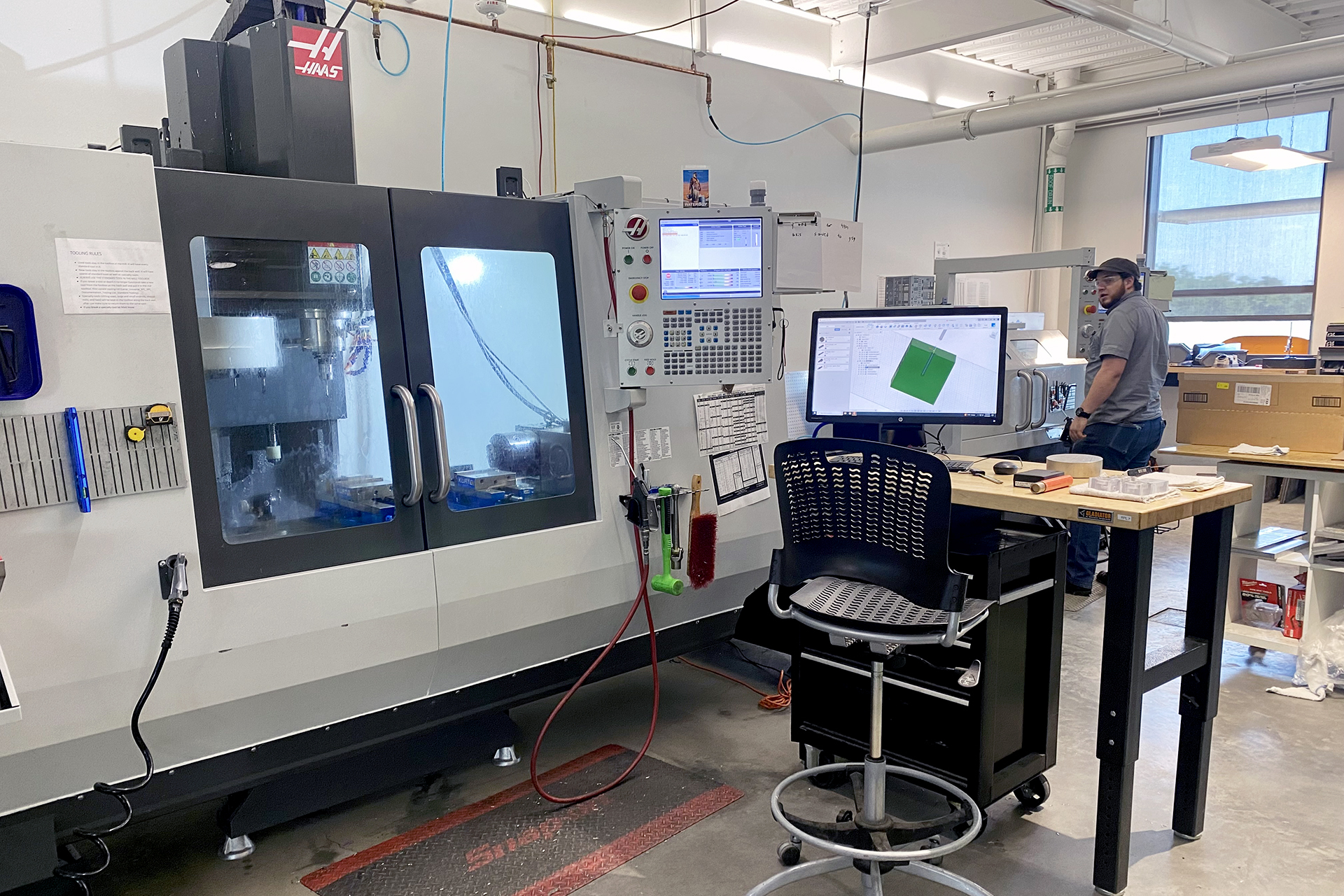

John Mizia, research associate in mechanical engineering, earned a $60,000 grant. Mizia is the director and chief engineer at the Rapid Prototyping Lab (RPL) at CSU’s Powerhouse Energy campus.

The research

Developing a wavelength specific, narrowband LED photochemical vaccine manufacturing testbed.

The idea

CSU has pioneered a vaccine manufacturing platform, SolaVax, that relies on riboflavin and broadband UV light to inactivate pathogens through a targeted nucleic acid photochemical reaction. This inactivated material forms the basis of the SolaVax vaccine.

Although research has shown that the photochemical process occurs at discrete wavelengths, the dominant illumination source for the current technology is based on broadband UV fluorescent lamps. This program seeks to build a narrowband LED illuminator that focuses on the wavelengths where the targeted riboflavin/nucleic acid photochemical inactivation occurs. A critical adverse effect of using wideband illumination is non-targeted virion damage. Wavelengths falling outside of the photochemical reaction region, notably in the high-energy UVC region, produce indiscriminate protein damage. This protein damage negatively impacts the subsequent human immune response.

The project continues to work on the custom built, high-intensity flow-through photochemical reactor called the “VacciRAPTOR.” The device was built by engineers who collaborated with Raymond Goodrich, executive director of the Infectious Disease Research Center, who is also a professor in CSU’s Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Pathology.

“We’ve been working with the Infectious Disease Research Center on this vaccine manufacturing concept for several years now. The next step in optimizing this technique is researching the impact of targeted wavelengths and this program will do just that,” Mizia said.

He said preserving the overall structure of the inactivated virions is critical to the downstream human immune response. Using broadband illumination that includes high energy UV light produces unwanted indiscriminate protein damage.

“The beauty of the targeted wavelengths concept is that you’re focusing on damaging the replication capability of the pathogen through nucleic acid damage, while at the same time preserving the other protein structures,” Mizia said.

The car analogy

“Let’s say I have a vehicle that represents the virion, and if I cut the vehicle in half, I can still tell that it used to be a car, right?” Mizia said. “But if I find some random part on the inside and yank it out, you’ll have a difficult time identifying what kind of car the part came from. The human immune response is similar in that it has to first be able to adequately identify a threat.”

“If we can eliminate the indiscriminate damage, then we can increase the downstream immune system response. That’s really the crux,” he added.

Promoting safety and security

The necessity for rapid and reliable production of vaccines was highlighted due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Hundreds of millions of doses of vaccine were needed urgently to stop the spread, morbidity and mortality associated with the disease. This need demands new approaches to produce vaccine materials. The CSU approach proposed here can afford a means to rapidly produce vaccine candidates not only for new, emerging disease threats but also for existing diseases where vaccine production costs and complexity limit availability and supply. Mizia said work at Solaris Vaccines is ongoing to improve current vaccines and to limit any future pandemics or virus terrorism through rapid vaccine manufacturing.

The Rapid Prototyping Lab. Photo by Mark Gokavi