The nexus of hurricane research

How did CSU’s preeminent hurricane research center arrive at a landlocked university?

podcast by Stacy Nick

published July 11, 2024

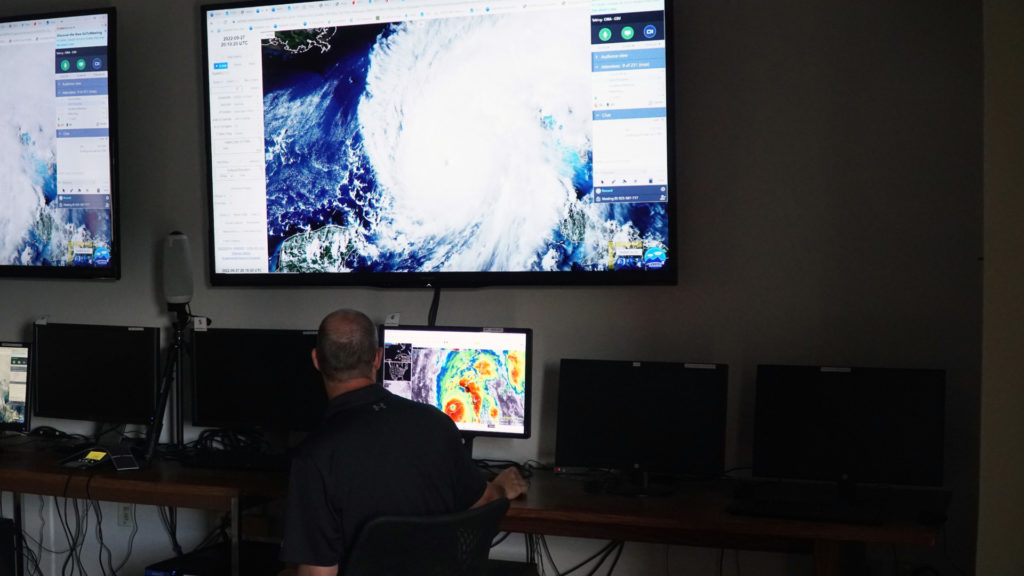

For the past 40 years, Colorado State University has been at the eye of a hurricane — or at least the eye of hurricane forecasting.

Despite its landlocked location, CSU is well known all along the Atlantic coast for its seasonal hurricane forecasts. Each spring, these forecasts predict the total amount and potential strength of storms for the upcoming hurricane season. The forecasts were first developed and shared by pioneering atmospheric science researcher William Gray, and are frequently used by media, officials and community leaders to inform the public and make planning decisions. Today, Gray’s former grad student Phil Klotzbach leads the effort to inform communities up and down the East Coast of the dangers the upcoming season presents.

Klotzbach is a senior research scientist for the Department of Atmospheric Science within the Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering, and along with a team of students, faculty and research staff, has authored the forecasts since 2006.

In late June, Klotzbach spoke to CSU’s The Audit about the University’s role in developing hurricane research, the increase in hurricane activity and destructiveness over the years, and what we can expect in terms of size and scale for future hurricane seasons.

(This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.)

HOST STACY NICK: Well, let’s start with what led you personally into this field of research?

KLOTZBACH: I’ve been fascinated with the weather since I was a little kid. I grew up in Massachusetts, in Plymouth, right along the water. When I was 5 years old, in 1985, we had Hurricane Gloria come through. It came through Connecticut but brought some pretty significant impacts, even in southeastern Massachusetts. Then when I was 11 years old, Hurricane Bob came through. That brought a lot more significant impacts. We had a lot of trees down. A tree came down very close to our house with that storm. So that really got me especially fascinated with hurricanes. I’ve been really interested in the weather for as long as I can remember. But right now, it’s all about trying to figure out what makes hurricanes tick.

So, what makes hurricanes tick?

Well, so the group that I work with, Michael Bell‘s group, we study hurricanes on all sorts of timescales. I lead the seasonal Atlantic hurricane forecasts, which were pioneered by Dr. Bill Gray all the way back in 1984. This is our 41st year of doing seasonal hurricane predictions. I was an undergraduate in Massachusetts studying geography, and I took a climatology class, and I was interested in hurricanes. The professor in the class said there was a guy in Colorado who forecasts hurricanes on a seasonal timescale. I thought that guy must be nuts. There’s no way you can do that. But I read up what he was doing and realized he actually knows what the heck he’s doing. I’ve been trying to follow in his footsteps and continue the seasonal hurricane predictions ever since.

It’s interesting, I think, that there’s a general sense of “what?” when people first hear that the top hurricane research is coming from Colorado. How did CSU come to be the epicenter of this type of research, despite being landlocked?

When people would ask Dr. Gray why we forecast hurricanes from Colorado, he’d say it’s because the storm surge can’t get you at 5,000 feet. But in all seriousness, basically, the guy who started the program was Herbert Riehl. And Herbert Riehl was asked to start the department. He was coming from the University of Chicago, which is still nowhere near hurricanes, but he was a big hurricane researcher at the University of Chicago. He started the department. Dr. Gray was finishing off his Ph.D. at the time, so he finished off his Ph.D. and followed Herbert to Colorado State University soon after. After Dr. Gray passed, the offer letter from Herbert Riehl to Bill Gray was found in his office. The original signed letter was still there. Bill Gray was one of the first guys in the department. Our department does all sorts of different research, but we’ve always had one or two faculty members really focused on hurricane research.

Does it ever feel weird for you, or does it just feel like, yeah, of course we’re at CSU. Of course this is happening here.

There’s a lot of hurricane research done up and down the Front Range of Colorado. We’re far removed from hurricanes, but I attend a lot of conferences which take me to places like Florida and Texas, so I’m certainly in a lot of very hurricane prone areas every year.

How has the team evolved since you’ve been there?

Dr. Gray formally retired a couple of years after I started, but I worked closely with him. He was working as an emeritus professor, so he and I worked very closely on the forecasts until his passing in 2016. Right about the same time, Michael Bell joined our department as a professor. He also went to CSU for his master’s, so I knew him from back in the early 2000s. But he came to CSU as a professor in 2016. So, after Dr. Gray passed, I started working with Michael. Now there’s several of us from Michael’s group that work on the seasonal hurricane forecasts.

Now, for people who don’t know much about the hurricane forecast. Can you give me a quick, basic explanation of how the forecast is done and how accurate it is? You start doing these forecasts in April and then do updates later, but that’s early to be calling what’s going to happen in August.

We have been doing seasonal hurricane forecasts since 1984. A lot of this goes back to the relationship Bill Gray discovered in the early 1980s, where when you have El Niño conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean, you get fewer hurricanes in the Atlantic. Basically, he discovered that when you have warmer than normal water in the central and eastern tropical Pacific, which is what you have when you have an El Niño, it shifts where the Pacific thunderstorms form a bit farther to the east. Because of that, you get increased winds up out of the west that increases what’s known as vertical wind shear, which is the change in wind speed and direction with height in the atmosphere. Too much shearing tears apart the hurricane. So, when you have El Niño years, you tend to have more shear, fewer hurricanes. La Niña years mean less shear, more hurricanes. This is one of the first relationships he discovered because you can predict El Niño usually several months into the future. So that gives you some seasonal predictability of Atlantic hurricane activity. It was the discovery of that relationship that really got him motivated to start doing these seasonal predictions. But now there’s a whole pile of different predictors, and those predictors have somewhat changed with time because the climate is not stationary. So, we’re always looking for ways to improve our seasonal forecasts. Certainly, I’d say we’ve come a long way since the original methodology that Dr. Gray pioneered in the early 1980s, thanks to a lot more sophisticated computer modeling than we had 40 years ago.

This season is forecasted to be one of the busiest on record. I think you had like 23 named storms and 11 hurricanes.

Yes, it is forecast to be a very busy season, and I can tell you there’s a ton of interest in this hurricane season. In April there were like 6,000 media stories on the seasonal forecast, about CSU. As we’re recording the podcast, I’ve done three hour-long webinars on the hurricane season already today. There’s a lot of interest in this hurricane season because it is forecast to be so active. The primary reason being that we had El Niño last year and it’s weakening very quickly, likely to transition over to a La Niña, which is colder water in the central and eastern tropical Pacific. That tends to reduce your shear, making the winds more conducive for hurricane formation. The Atlantic right now is record warm. So, we have what we call the main development region, which is the main region where hurricanes develop. It’s running at record warm levels, so that provides more fuel for the storms. It also tends to be associated with a more unstable atmosphere, more lower pressures, all these things that you want if you’re looking for a busy hurricane season. So, with the forecast from our group, from NOAA, from all these different groups calling for such an aggressive hurricane season, certainly there is a lot of interest. I started doing interviews on this hurricane season back in January just because the Atlantic was so hot. People were already starting to talk about the season in the dead of winter. And normally in January I don’t do very many interviews, so there’s been a lot of interest in this season for a while now. Anticipation is growing as we are officially in the hurricane season.

After doing this for so long, where do you see the trends going? While I’m wishing that your answer would be we’re going to see fewer and less destructive storms, I feel like that’s not the direction things are going.

We published some papers looking at this a few years ago. There are big increasing trends in damage from hurricanes going back to 1900. Most of that increase in damage is just effectively more people and more stuff along the coastline. As people move to the coast, you have more people there, so you increase the exposure to these catastrophic weather events. That’s been a big driver of the increase in damage to date. Of course, we can always delve into the realm of climate change and how it may be impacting hurricanes. I mean, certainly with just the sea level rising, that means when you have that storm surge or that wind-driven increase in water level that you get with hurricanes, that storm surge is going to penetrate farther inland because the sea level is higher. We also know that with a warmer atmosphere, we get more rainfall because a warmer atmosphere can just hold more moisture. Consequently, that also can increase the damage from storms. There’s a lot of discussion and debate as to what other characteristics of hurricanes are changing. That would be a topic for a six-hour podcast, but in general, the answer is probably not more storms, maybe even fewer storms, but potentially the storms that we do get will be a bit stronger. It gets pretty complicated. Because of climate change you warm the surface, which warming the ocean provides more fuel for the storm. But you also warm throughout the atmosphere, and higher up in the atmosphere you warm even more, and that tends to stabilize the atmosphere a bit. That tends to counteract some of what you would expect. But overall, we do think that the warmer atmosphere will likely lead to slightly stronger intensities, as well as probably more volatile storms, so storms intensifying faster and weakening faster than they currently do.

The warm ocean temperatures that contribute to those larger storms that we’re seeing this year and last year – are those the new normal for us, and if so, is that related to climate change?

We had a very pronounced change that happened at about March of last year. If we’d done this podcast in February 2023 and you talked about the Atlantic, I’d have said the water temperatures are pretty much dead-on average. Not much is going on. But in March of last year, the subtropical high pressure — so the Azores High and the Bermuda High — got very weak. Why the heck do we care about that? Well, when the pressures there fell, the winds that blow across the tropical Atlantic, which we call the trade winds that blow from east to west, those winds got a lot weaker because you weakened your pressure gradient between the subtropics and the tropics. Why that matters is because weaker winds blowing across an ocean surface cause less evaporation. Like when you get out of a swimming pool on a windy day. It cools very quickly. But if you get out of a swimming pool and it’s calm, you don’t get cold as fast. When there was less evaporation, that allowed the water to warm extremely quickly from March to about June, and they just stayed elevated since then.

I would say overall weather events are what made the Atlantic as hot as it is over the last year or so. But climate change kind of loads the dice towards these kinds of events. There’s still some uncertainty as to exactly why it hasn’t gone back at all, like why those hot temperatures persisted. They obviously cool off in the winter, but relative to normal they stayed elevated. There’s some question about that. Some of it may be due to the circulation that we normally get with El Niño, which we had last winter, typically it reduces the strength of your subtropical high. So, the subtropical high was weak, and then it remained weak because of El Nino. Now it’s just so dang hot. When it’s really hot, that tends to force lower pressure. Unfortunately, it’s really getting too late for this hurricane season to see much, if anything, other than the warmest or the second warmest Atlantic on record.

With this kind of research, the historical records for hurricanes are not extremely complete, because it’s not like pulling an ice core or carbon dating will tell you what category a storm was when it landed in Florida in 1712. So, there’s still a lot of guesswork in comparison of seasons and predictions of how storms will move. What does that tell you about the need for this field of research and future advancements?

When we talk about seasonal hurricane predictions, our predictions that we use build on historical data going back to the late 1970s. The reason we start then is because that’s when we had pretty good satellite coverage globally. So, we have a decent idea of what the atmosphere is doing, and a fairly good idea of what the hurricane seasons were doing. Now you can go back further. Dr. Gray started this in the ’80s. He went back to 1950. He would always call us snobby using just the newer data. But as you go back in time, there’s more uncertainty in both the hurricane data as well as in what the atmosphere ocean was doing. If you go even further back, there are big gaps in World War II and World War I, a lot fewer observations during that time. Even the late 1800s may be more reliable than WWI and WWII, just given the lack of observations during those two world wars. One battle we’re always fighting is whether you build your models on the more recent data where you’re confident, but you only have 40 or 45 years of data, or go back further and build on a lot more realizations of the atmosphere and ocean, realizing that there’s going to be higher uncertainty. It depends on exactly what you’re trying to do, but with seasonal forecasting, again, we typically go back about 40 to 45 years.

Unfortunately, like you mentioned, we don’t have 10,000, 50,000 years of data, which precludes many artificial intelligence techniques employed in many areas of meteorology. When you only have 40 to 45 data points, you don’t really need artificial intelligence to tell you what you should be using to predict storms. It’s a lot more useful in, say, day-to-day weather prediction or on sub-seasonal climate prediction, say one to two weeks where you have a ton more realizations. Then those artificial intelligence techniques become a lot more helpful. But on a seasonal timescale, when you only have 40 to 45 years, there’s not that much you can’t do by just like looking at maps and picking it out from that.

Where do you see CSU’s hurricane research going in the future?

Our group does a ton of research on all different sides of things. One of my focuses is on the seasonal hurricane predictions. But our group studies everything from what’s going to happen with hurricanes in the next five or 10 minutes to what’s going to happen 100 years from now. From the seasonal hurricane prediction side of things, what we’ve done is always predict whether the Atlantic looks busy or quiet, but what we’re trying to do is get more regionally specific. So, on June 13 you can’t say there’s going to be a hurricane hitting Brownsville on Aug. 9. We’re never going to have that kind of scale, but trying to get more regional with specific regions that might be impacted by storms. We also do a tiered approach to forecasts. April is our first forecast, and we update it in June, July and August. Starting in August we issue forecasts every two weeks. Those two-week forecasts are just for activity during a two-week period. The reason why we do a two-week period is because you can have a very busy time during a quiet season or a quiet time during a busy season, but also, then you can start to look at specific regions that may be impacted by storms in the next week, two weeks. Last year, for example, Aug. 18, we put out a two-week forecast and said the Atlantic looks very busy. The Central and Eastern Atlantic looks quite busy. Most of those storms are just going to go out in the ocean and not be much of a threat, but there does appear to be something in late August, maybe northwest Caribbean, southern Gulf of Mexico. That’s the system that you want to be watching. That turned out to be Hurricane Idalia, which was the one major hurricane that hit the U.S. last year. That’s certainly not something we can say two months in advance. But when you start to get more towards that two-week time frame, then you start to kind of hone in on areas that may be of significance. That’s the cascade of forecasts that we issue. And then at the end of every year, we also do an extensive verification where we write up the season, describe what in the forecast worked well, what worked poorly, and then talk about some ideas of what we might do the following year to improve the forecast.

And you have an update coming out soon, right?

I will update it again on the 9th of July and a final update on the 6th of August. And oftentimes people say you’re cheating. You can’t do this forecast. It’s two months into the hurricane season, but about 95% of your major hurricane activity, which are your category three, four and five hurricanes, occur after the 1st of August historically. So, it gives you this kind of one last estimate to fine-tune the numbers. One last shot at a mulligan if you realize we really butchered stuff up to that point, but there’s a lot of climate signals information. July is actually a really helpful month for doing these seasonal forecasts. And normally in July, thankfully, we don’t have that many storms, so it does give people kind of one last shot at here’s our best estimate at that point. And, with the August forecast, that 1st of August forecast, we do issue our first two-week forecast so we can at least say, OK, you know, the rest of the season looks busy the next two weeks. Last year we said busy season, but the next two weeks look fairly quiet. We expect a busy season but not the next two weeks. So, at least then you kind of can start to highlight again when you think storm activity during the season is more likely to occur.

You mentioned that sometimes it’s a mulligan. If you don’t mind me asking, what’s that like? I mean, you can’t be perfect. It’s a forecast.

Correct, yeah. Even if you have perfect knowledge of the atmosphere ocean, you know exactly what happened during the season, you can only get about 60% to 70% of the variability in hurricane numbers because again, you’re trying to forecast weather events on climate timescales. Basically, in a way we don’t actually really forecast hurricanes. We actually forecast what the environment looks like. If you say what the environment looks like this year, we expect it to be extremely conducive. Therefore, an environment that conducive typically yields about 11 hurricanes. So that’s how we come up with the forecast. It’s not that we’re predicting there’s going to be a hurricane forming Aug. 9. That’s not what we do. But even if you have that perfect knowledge, hurricanes are weather events. Even if the entire basin is super conducive, there’s one spot where it’s not, and that storm finds that one non-conducive spot. You could have it or storms could interact with each other. Storms could go over land. They miss land. There are all these different things that come in that can cause noise in the system. So, even perfect knowledge of the large scale only gives us so much.

But I’ve certainly been a part of several pretty lousy forecasts. The most recent one that was a real stinker was 2013, where we forecast nine hurricanes, and we got two. That’s the baseball equivalent of forecasting the Chicago White Sox to have won the World Series this year. Would that happen again? I would say we wouldn’t bust as badly. We’re always tweaking our models and using newer data. When we look at 2013 with the models that we currently have retrospectively, the models still don’t go as low as what happened, but they certainly call for maybe near to slightly below average, as opposed to well above average.

We think the odds of a bust this year are extremely low, just given it’s mid-June, and the water temperatures in the Atlantic are like you normally see in late August. So, some crazy stuff would have to change to make this a quiet season.

Well, Phil, thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate you being here.

Sure, no problem. Take care.

That was CSU hurricane researcher Phil Klotzbach. I’m your host Stacy Nick, and you’re listening to CSU’s The Audit.