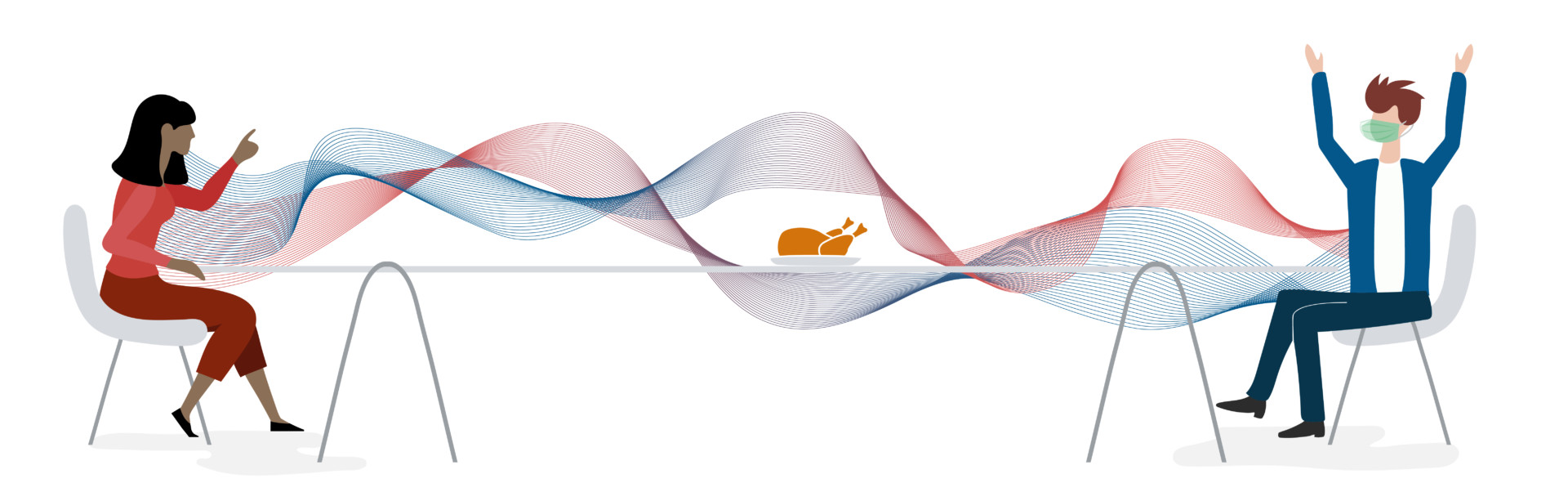

As the nation heads toward Thanksgiving and other winter holidays — closing out a year that has seen a fiercely contentious election, arguments about the handling of a pandemic and protests over racially motivated violence — talking politics with that loud uncle at the socially distanced family gathering may cause some anxiety.

But as faculty experts from the Colorado State University System point out, those conversations don’t need to be stressful — as long as you’re a good listener. Even if it’s just on Zoom.

“Listening is an active process, and you have some control over how those conversations around the table go,” says Elizabeth Parks, an assistant professor of communication studies at CSU-Fort Collins. “The assumption that other people will see what we mean can lead to misunderstandings. Sometimes as listeners we just need to show people that we’re trying to understand. Often it’s about the process, not the goal.”

Taking time to make people feel heard, even if we disagree them, can be as simple as silence.

“We’re not very good at silence, as a cultural norm,” Parks says. “We feel the need to fill blank spaces because we place so much value on words, and being right. We have public speaking classes, but not public listening classes. Listening is an invitation that creates space for others to speak.”

“We’re not very good at silence, as a cultural norm. We feel the need to fill blank spaces because we place so much value on words, and being right. We have public speaking classes, but not public listening classes. Listening is an invitation that creates space for others to speak.”

— Elizabeth Parks, assistant professor of communication studies, CSU-Fort Collins

A team mindset

For Ryan Strickler, an assistant professor of political science at CSU-Pueblo, being a good listener can be an uphill battle.

“Our brains aren’t hardwired to have constructive conversations across difference,” he explains. “Because we are so tied up in group identity, and how that defines our own self-identities, we tend to only seek information that supports our team. There is neurological research showing that the pleasure centers in our brain are activated when we’re told that we’re right.”

Parks, who is the dialogue and diversity specialist for the Center for Public Deliberation, agrees. Instead of surrounding oneself with like-minded people in social media networks that reinforce existing views, she recommends exposing oneself to difference, to people who disagree. Parks adds that a good listener averts creating defensiveness in another person — by giving them space and not escalating the situation.

“A lot of our defensiveness comes out of fear,” Parks says. “We can get combative, and when others get defensive, it makes you feel like you’re winning. Or, if I get the feeling that someone’s trying to fix me, pride gets involved, and I may react rather than respond.”

Advice for good listening

Both Parks and Strickler offer a variety of tips for listening across difference, whether it’s at the dining room table, in the classroom, or in a social media exchange.

Strickler, a political psychologist whose specialties include partisan polarization, describes the concept of “intellectual humility” — the idea of being open to the possibility that one does not know absolutely everything.

Parks adds that coming from a place of humility increases the chances that, as a listener, you will provide speakers with what she calls “margins,” or the time and space they need to feel heard. Being silent — or even gently responsive with nods, a quieter tone, slower speech or clarifying questions — can show that you respect other people and are genuinely interested in understanding their position, even if you disagree.

“This concept has made me more humble, because I’m just as susceptible to going into a silo as anyone,” he says. “I may be prone to not having complete information, or prone to biases. Recognizing intellectual humility doesn’t mean you have to run out and read everything on both sides of an issue. It just means you have recognized the possibility that more information-gathering is possible.”

“It can be ‘us for them’ instead of ‘us vs. them,’” Parks explains. “Just because we’re different doesn’t mean one side is bad. These are people we care about; we want to avoid making them monsters or objects. We want to say, ‘It’s because you matter to me that we’re having this conversation. I still want your good.’”

“Recognizing intellectual humility doesn’t mean you have to run out and read everything on both sides of an issue. It just means you have recognized the possibility that more information-gathering is possible.”

— Ryan Strickler, assistant professor of political science, CSU-Pueblo

Class discussions

In his classes, Strickler says, he is careful to set the stage for difficult conversations by scrambling up easy partisan cues: He focuses on policies or arguments, without mentioning political parties or candidates.

“If you ask things in a more neutral, logical way, there is a lot more nuance, but that gets lost when you’re in the fire of partisanship,” he notes. “Also, if from the beginning, you create norms and expectations that we want to understand the other side, that helps keep it civil.”

As for the extended family conversations around the holidays, Parks suggests deciding beforehand which discussions one wants to have, and with whom. She says that pausing — to take a bite or a sip of water, for instance, and letting someone say their piece – can defuse conversations that are escalating into conflict.

Parks also notes that deferring topics to a later time, perhaps in one-on-one discussions, might be more productive than the performances that can occur in front of an audience — especially when two people can focus on something else, like a roaring fireplace or fixing a bike together. Strickler agrees, suggesting having conversations in settings where people are working on a common goal as a team, like doing a jigsaw puzzle.

Role of media

Both CSU experts agree that the news media and social media can accentuate polarization and difference over moderation and commonalities.

“There is a disinhibition effect online; you are less inhibited because you’re talking to a screen instead of a person, and the norms of humility and respect are not there the same way,” Strickler says. “It’s easy to overreact to social media; it’s not representative of real political life.”

He adds that news media outlets tend to emphasize conflict and division to stir emotion and engagement — which manifests on their social media accounts as highly coveted comments, likes and shares.

“People are actually a lot more moderate than you’d believe,” Strickler says. “It may feel like we’re hopelessly divided, but there are many people who are more moderate than is reflected in the media. And when there are media reports about how polarized we all are, it creates more polarization.”

But there is still hope.

“The good news is, as we’ve continued to polarize, I think people are recognizing more and more how bad it’s gotten,” Strickler says. “More people are expressing disgust at the vitriol. Maybe the Thanksgiving dinner table is the place to begin breaking that pattern.”