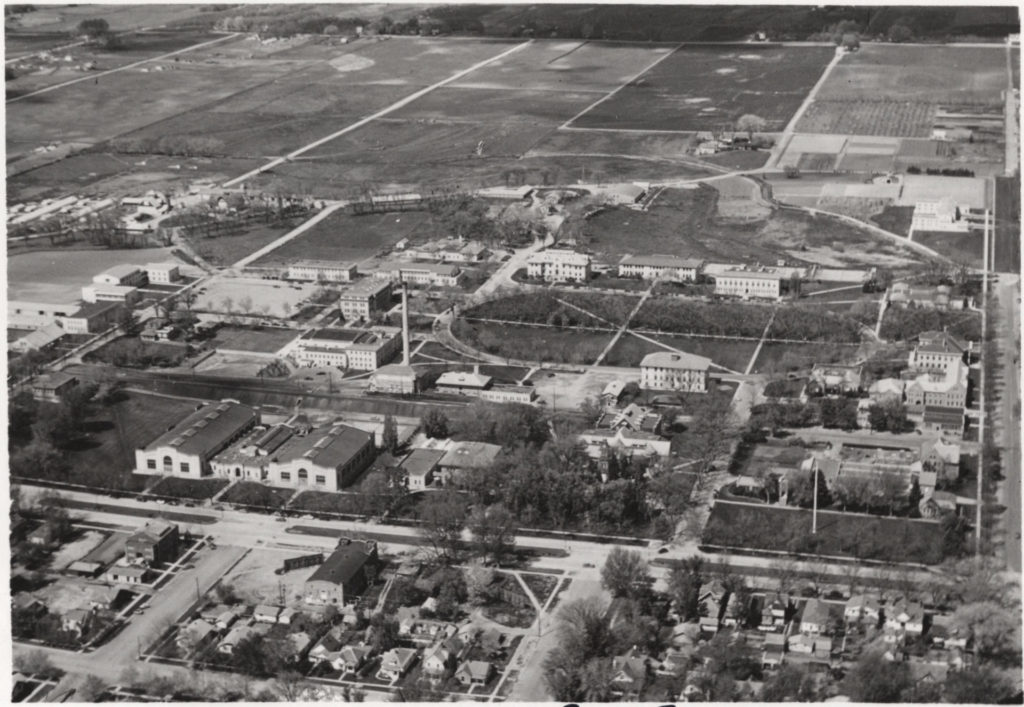

An aerial look at the CSU campus and Fort Collins in the early 1900s versus modern times and the proliferation of green spaces.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Colorado River Compact, an innovative and influential legal agreement among seven U.S. states that governs water rights to the Colorado River. In recognition of this anniversary, the Colorado State University Libraries will be spotlighting a series of stories in SOURCE about the ripple effects of this 100-year-old document on diverse people, disciplines and industries in 2022.

Previous stories in this series include: How Colorado water history shapes the science of snow and why Western river compacts were innovative in the 1920s but couldn’t foresee today’s water challenges.

One hundred and fifty two years ago, Colorado Agricultural College’s first buildings sat among sagebrush and prairie grasses. As the campus grew, its center became enshrined in a green meadow ringed by elms, a space now known as the iconic Oval.

Today, Colorado State University’s green spaces are woven into the tapestry of campus life – from the Intramural Fields to Monfort Quad, they serve as informal parks for students and faculty alike to revel in the beauty of the Front Range.

A western campus shaped by urban ideals

These spaces speak to the larger power of the designed landscape in American life. Popularized by the public park movement and Frederick Law Olmsted’s layout of suburban landscapes in the late 1800s, large, green public spaces provided serene outdoor recreation in cities after the Industrial Revolution.

“The democratic nature of large, open spaces on the East Coast was brought with people as they moved West,” said CSU landscape architecture professor Lori Catalano. “It was a way of creating central green spaces that were shared, but the plants and ideas migrated from a humid climate in the East to the semi-arid climate in the West.”

As a growing land-grant institution, CSU’s adoption of the green aesthetic instilled the idea of parks as public spaces accessible to all.

Though the Oval’s first elms were planted in 1881, it wasn’t until 1919 that it became the center of campus, soon after Fort Collins’ City Park was established. These spaces signified how far green spaces had spread from their wealthy urban roots and democratized access to parks in northern Colorado.

“As humans, plants, and animals moved west, they modified the landscape,” Catalano said. “Alfred Crosby’s concept of ecological imperialism helps explain how emigrants moved westward with a variety of diseases, plants, and animals co-creating an environment that reinforced the presence of open grassy fields with trees.”

After World War II, green spaces were adopted into front lawns by middle-class residents seeking a taste of luxury. CSU’s own green aesthetic bloomed as it grew. Spaces like the Monfort Quad, the Intramural Fields and the Lagoon complemented new architecture while creating new outdoor spaces for students between classes.

Green oases in the prairie

“Traditionally on campuses, buildings are grouped to create a series of outdoor rooms,” Catalano said. “Aesthetically, people and students expect large areas of green lawns with trees – they don’t expect it to look like prairie.”

In the American West, these green landscapes live on and signal the continuing legacy of centuries-old ecological imperialism, but they contrast with the region’s naturally dry, beige prairies. CSU’s green spaces remain a central part of its identity and help unify landscapes without sacrificing flexibility and durability – which is critical for a campus that has thousands of students traverse its grounds during the school year.

“College campuses are used a lot like parks and need a surface that is flexible and durable,” Catalano said. “Grass is very durable, as it can tolerate students walking over it, (playing) frisbee, picnicking, whereas our native grasses that require less water cannot tolerate that level of compaction.”

Lawns are also simpler to maintain compared to native plants – all that’s required is mowing, fertilizing, and watering. But throughout the American West, green lawns contrast with dry, semi-arid landscapes and may not survive a resource-scarce future.

“If campus reflected the natural landscape of Fort Collins, we’d see grasslands with Cottonwood trees and peach leaf willows along waterways,” Catalano said. “Visually, lawns hold a cultural power. They look good, they’re green … it’s what we know and what makes us comfortable.”

What will green spaces look like in the future?

With an unprecedented mega-drought in the Colorado River Basin, some states have challenged the ubiquity of green lawns.

In Las Vegas, authorities started paying people to remove their irrigated lawns in the 1980s, and the program has been largely successful in curbing residential water use. As of 2021, any “non-functional” lawns are banned in Las Vegas to conserve water, reflecting how Nevada’s lower allocation of Colorado River water is already stretched thin.

In Colorado, House Bill 1151, which was signed into law this past April, requires the Colorado Water Conservation Board to create a statewide program with $2 million in funding to incentivize replacing grass with “water-wise” landscaping.

But, according to Catalano, changing how people understand and perceive the landscape can prove daunting.

“It takes a lot of will and intention to make a commitment to changing the landscape,” she said. “We could incentivize it, but one challenge is, the price of water is relatively inexpensive – it takes someone who’s passionate and intentional about it to be enticed by incentives, because there’s not a huge financial gain. It’s a little like solar – we all want it, but how much are we willing to pay for it?”

Curbing water usage through changing landscape aesthetics will be necessary to ensure the long-term health of the Colorado River Basin.

In June, the U.S. government declared that the basin must cut its water usage by 2 to 4 million acre-feet or risk federal intervention. Meanwhile, CSU researchers found that most streams flowing through the Denver parks system only exist because of runoff sprinkler water. Reducing water consumption through limiting green lawns, then, could prove effective.

Though CSU’s campus design now seems set in stone, its history reflects a century of cultural changes that have cultivated tree-lined avenues, sprawling fields and verdant quads. A long cry from Old Main set atop rolling plains, the future of these unifying spaces will be influenced by the state of the Colorado River Basin and pending water shortages.

“Landscapes are often unseen, undervalued, and not understood. When people can’t see or don’t understand the processes and systems involved in creating and maintaining landscapes, it is difficult for them to value making a change,” she said. “When we begin to see and value alternative landscapes that require less water, reducing the dominance of lawns is possible.”