1918: When the flu came to CSU

story by Kate Jeracki with additional research by Mark Luebker, Office of the President, and Vicky Lopez-Terrill and Cory Rubertus, University Archives and Special Collections published March 23, 2020Photo source: University Archives and Special Collections

Fulfilling its land-grant mission brought the influenza pandemic to the Colorado Agricultural College in 1918, and then, as now with Colorado State University’s response to COVID-19, quarantine and serious hand-washing were the first lines of defense against the spread of disease.

The Morrill Act of 1862, establishing institutions of higher education for all who wish to learn, specifically included military training, along with the agricultural and mechanical arts, as required fields of instruction. As the United States prepared to enter World War I, CAC constructed new barracks to house SATC – Student Army Training Corps – members headed to officer camps before joining the fighting in France.

A total of nearly 750 trainees, both officers and enlisted men, arrived on campus at different times over the summer of 1918, although where they had been before coming to Fort Collins is unclear. A number of the officer trainees came from all over Colorado, from Paonia to Denver.

Historical records show that the first recorded cases of what was later identified as a strain of H1N1 virus – erroneously called the Spanish flu – in Colorado arrived at the University of Colorado Boulder and in Colorado Springs on Sept. 20, with detachments of soldiers from Montana who were already ill.

CSU’s first historian, Professor Ruth J. Wattles, reported that the first SATC cadets were inducted into the Army in a ceremony on campus on Oct. 1, 1918, apparently flu-free. The first three cases – and the first fatality – appeared among the trainees on Oct. 4. By Oct. 12, the number had grown to 30, and to 94 by Oct. 14. Wattles reported that of 150 men who arrived on campus together, half were in the hospital within 24 hours.

For a time, trainees who were not symptomatic were required to attend classes – a good show of military discipline, but a bad call for public health.

The flu was not seen as a serious threat to the college yet, despite a warning from the State Board of Health on Oct. 7. The Oct. 10 edition of The Rocky Mountain Collegian offered suggestions on how to avoid getting sick.

Avoid needless crowding – influenza is a crowd disease.

Your fate may be in your hands – wash your hands before eating.

– The Rocky Mountain Collegian, Oct. 10, 1918

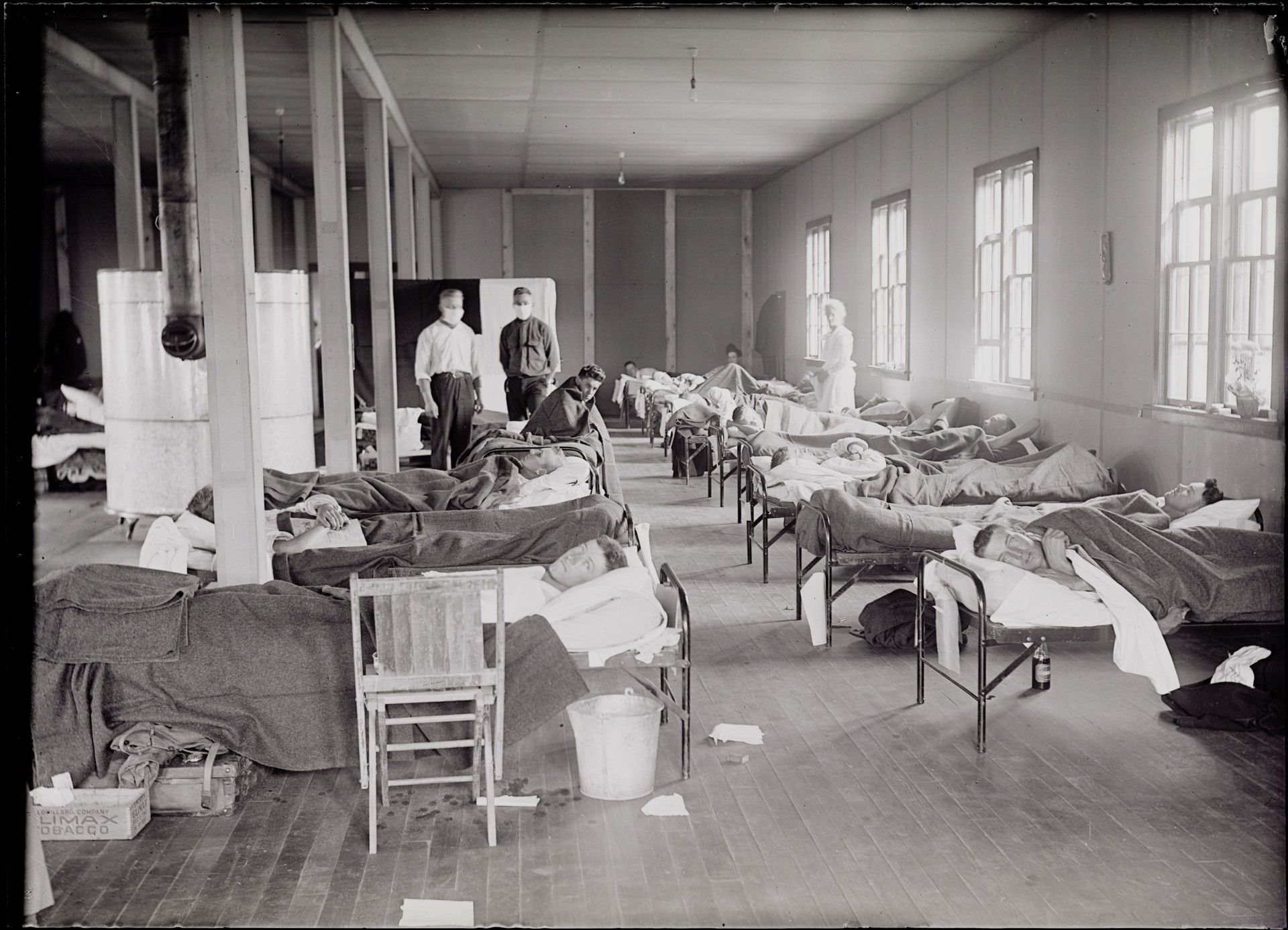

Hospitals on campus

As the U.S. prepared to enter World War I, nearly 750 trainees arrived on campus at different times over the summer of 1918. By the fall, there were 94 cases of a strain of H1N1 virus, with military patients filling the newly constructed barracks. Photo source: University Archives and Special Collections

The military men who fell ill were treated in a makeshift hospital set up first in the south wing of the barracks and then in the entire building as their numbers grew. A separate facility for civilian patients was set up on the third floor of the Civil Engineering Building on the Oval, now known as the Statistics Building, which houses offices and classrooms for the College of Natural Sciences.

On Oct. 16, Colorado Gov. Julius C. Gunter prohibited all public and private gatherings across the state.

On Oct. 17, The Collegian reported that 19 men students were ill in the Civil Building, “and a few cases reported among the girls.”

Under the direction of the head of the Department of Home Economics, Inga Allison, each facility had a “diet kitchen,” staffed by junior and senior students, to feed the sick. Allison and other female faculty members emptied the garbage and did the janitor’s work when he became ill, unwilling to unnecessarily expose the female students to the illness.

On Oct. 24, campus was closed to civilians for two weeks.

“It is hoped that the epidemic will have spent itself in that length of time,” The Collegian wrote. “Nearly all civilian students have gone to their homes, and the strictest kind of quarantine is maintained on the campus. The gates are boarded shut, and guards will prevent anybody who has not a special permit from entering campus.”

The closure extended longer than expected. Classes did not resume until Nov. 21, 1918, “with an attendance of nearly 100 percent,” according to The Collegian.

Deadly infection

Nurses and a doctor help patients in the Civil Engineering Building, now known as the Statistics Building. The doctor is standing next to the bed of a patient who has pulled the covers over his head. Photo source: University Archives and Special Collections

All told, 15 SATC trainees died on campus, as well as one faculty member. The fate of those civilians sent home is not part of University records, but the pandemic of 1918 is remembered as one of the first infections that swept the globe. It infected one-third of the world’s population, with a mortality rate of 2.5%, resulting in 50 million deaths.

“Novel influenza viruses tend to have a pretty localized geographic origin,” said Lorann Stallones, CSU professor of applied social and health psychology who specializes in epidemiology. “It appears this one occurred around the same time in Asia, Europe and the U.S., so researchers have not pinpointed the geographic origin of this virus.”

Some research places the U.S. origin close to home, specifically the interactions between birds and swine on farms near the Kansas-Colorado state line. By the time it moved to humans, it could be transmitted from person to person very efficiently and was very lethal.

Army camps in Kansas had some of the highest infection and mortality rates in the nation, then seemingly healthy but exposed soldiers were shipped to Europe, exposed others to the virus, and the survivors brought a slightly different version back to the States.

Aside from the fact that barracks and troop ships are notoriously good places to transmit respiratory diseases, the flu took its greatest toll on younger people, perhaps because it was related to a strain that had affected the older generation previously. The deadly outbreak that hit Fort Collins was actually part of the second of three waves of infection, with the first, milder wave in the summer, and followed by a wave that began in February 1919, peaked in March and tapered off in April, according to Stallones.

Quarantine

As there were no vaccines, antivirals or ventilators to slow the 1918 pandemic, that left quarantine as the most effective response.

“Quarantine has been used since the 14th century to keep ships from bringing contagious diseases from one place to another, even before we knew anything about infectious agents, transmission patterns or the like,” Stallones said. “It was used to control the 1918 outbreak, and in communities that did not practice some form of quarantine, they suffered higher rates of infection and death.”

In fact, the mountain town of Gunnison is a case study for the effectiveness of quarantine during the 1918 pandemic. Anyone arriving by train had to spend two days in sequestration before leaving the station, and cars were not allowed to stop within the county unless passengers also entered quarantine – with legal penalties for violators.

With a population of 1,300 and only two major entrances to town, Gunnison could strictly enforce its regulations, and it worked. During 1918, there were only two cases of influenza reported in the county, neither in the town, and only one resulted in death.

“Our understanding of outbreaks of respiratory diseases suggest that the outbreak ends when all the people susceptible to the disease have been infected or have been protected from coming in contact with someone who is infected,” Stallones explained. “Social distancing is a form of quarantine imposing distance between people to ensure there isn’t transmission of the virus from person to person – through droplets, close contact or on surfaces or things infected people have touched.”

Today’s state population – and a student body of more than 33,000 enrolled at CSU, compared to about 400 in 1918 – requires the cooperation and compassion of many more individuals to contain the COVID-19 outbreak.

CSU COVID-19 response

For the latest information on Colorado State University’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, visit covid.colostate.edu.