‘Exquisite resolution:’ Microscopes illuminate hidden, intracellular worlds

by Anne Manning | April 20, 2017 8:17 AM

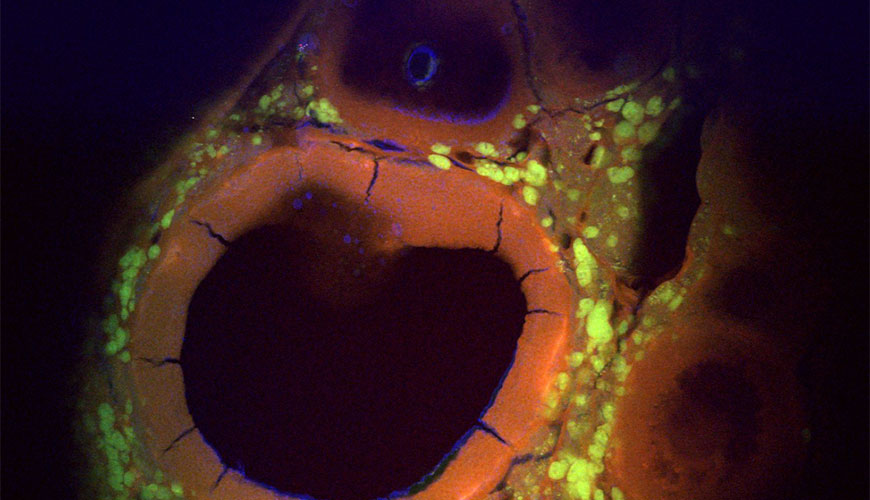

A multimodal, multiphoton image of the antral follicle in a mouse ovary. The image was captured with a fluorescence microscope.

Like the plastic tips on shoelaces, telomeres are bits of genetic material that cap the chromosomes inside our cells. Damage to these protective caps is linked to disease, and scientists like Chris Nelson are on a quest to know why.

Nelson, a graduate student in the lab of Professor Susan Bailey in Environmental and Radiological Health Sciences, is using a fluorescence-detection microscope at CSU to visualize and study telomeres – much too small to see with the naked eye.

This powerful microscope, called a Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence-Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscope (TIRF-STORM), is one of several instruments that make up CSU’s Microscope Imaging Network[1] (MIN).

The MIN, open to all university researchers, is a centrally funded consortium of research microscopes for live- or fixed-cell biological imaging. This resource gives scientists like Nelson and Bailey access to cutting-edge equipment they’d otherwise have to buy, or leave campus to find. The MIN is one of four Foundational Core Facilities[2] supported by CSU’s Office of the Vice President for Research.

“Without the MIN, our project would not have been possible,” Nelson said. “There is enormous overhead associated with many specialized forms of microscopy, so it’s important that we use these technologies as efficiently as possible for scientific discovery.”

The TIRF-STORM, which retails for more than $300,000, can do superresolution imaging, a technique that skirts the natural diffraction limit of light to offer crisp images of things much smaller than cells.

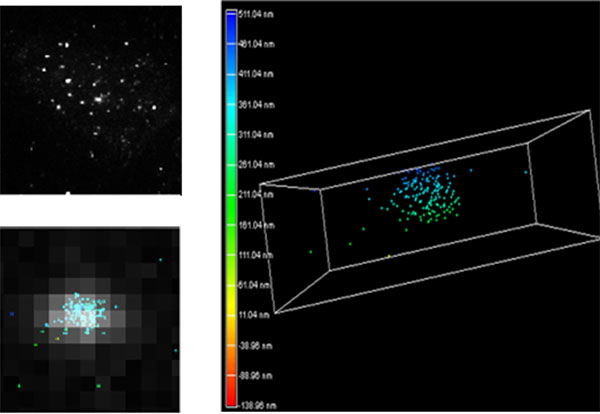

In order to visualize their telomeres using superresolution, Nelson and Bailey first tagged them with fluorescent probes. “Conventional fluorescent microscopy of telomere-bound probes makes each telomere indistinguishable from the next – a fuzzy glowing dot, roughly spherical in shape,” Nelson explained. “With STORM, each telomere becomes unique in shape and allows us to evaluate them at the level of the individual fluorescent probe such that we can determine how densely or loosely they are packed – a surrogate to how tightly folded the DNA is.”

Top left: A conventional fluorescence microscopy image of all the teleomeres in a cell. Bottom left: A map of fluorescent probes detected by the STORM microscope, overlaying a single telomere from the conventional image. Right: the same map of probes from an individual telomere, enlarged and in three dimensions. Credit: Chris Nelson/Bailey Lab

The MIN is led by Director Jeff Field[3], a physicist by training who also works closely with electrical engineering professor Randy Bartels to develop new imaging techniques and instrumentation[4]. “I love working on applying physics techniques and engineering tools to biological systems, and working at that interface,” Field said. “Every time I interact with someone who wants to solve a biology problem, I learn a little bit more – like what are the holes in imaging technology, and what are the things we’d like to do that don’t exist yet?”

The MIN operates under a fee-for-service model; users pay for time and training on the microscopes. Like all the foundational cores, the MIN offers Ph.D.-level skills and knowledge, through Field and a team of experts, to educate users and help them decide which instrument they need.

Deep roots

The MIN is managed through the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology in the College of Natural Sciences. It has been a centrally operated campuswide resource for nearly 10 years, but its history stretches back further than that.

Jim Bamburg, emeritus professor of biochemistry and molecular biology, founded the MIN and serves on its board of directors.

“In 2008, when the first call for research infrastructure applications came out from the [Office of the Vice President for Research], we put forward a proposal to bring together many of the dispersed microscope units on campus under a single committee,” Bamburg said. “And we called this the MIN.” Since then, the model has saved researchers, colleges and departments hundreds of thousands of dollars in equipment purchases and service contracts. The MIN was officially named one of CSU’s Foundational Core Facilities in 2015.

“As faculty, all of us know where our money comes from,” Bamburg said. “Why shouldn’t we do the most we can for everyone, with the money we have, since people are investing in us and want the best to come from our results?”

What’s available?

As a result of its incremental history, MIN microscopes are scattered throughout different physical locations, including one at the Foothills Campus, as well as in the Molecular and Radiological Biosciences Building and the Anatomy/Zoology Building.

Among the offerings: two electron microscopes, three laser scanning confocal microscopes, a spinning disk confocal microscope, and two wide-field microscopes, as well as the superresolution TIRF-STORM that Nelson and Bailey use.

The TIRF-STORM and spinning disk microscopes detect fluorescence, and are especially designed for live-cell imaging.

Advances in fluorescence microscopy have allowed scientists to visualize things, while still alive and dynamic, that are just nanometers in length. Such microscopes are sensitive to fluorescent probes – glowing tags that bind only to certain proteins of interest – which have opened new doors for targeted, intracellular studies.

“These are things we used to have to extract and purify, and see how they behaved in test tubes,” Bamburg said. “Now, we can look at their behavior inside the cell. We can look at mitochondria, lysosomes, or even the nucleus of a cell.”

Electron microscopes, also available through the MIN, can go to much higher magnifications than fluorescence microscopes, but they’re not useful for live-cell imaging because they would destroy the samples. Electron microscopy requires vacuum chambers and fixed-tissue staining with heavy metals. These microscopes offer high-resolution, molecular-level imaging.

Customized solutions

In addition to providing access to commercial microscopes, the MIN can also provide pathways to customized instruments tailored to specific users’ needs. Field consults with potential MIN users to determine whether the microscopes in the core facility can provide what they need. In some cases, such as the telomere project, the right instrument for the job is already in place and ready for use.

Yet many researchers need data beyond what can be provided by a MIN microscope. In such cases, Field builds on over 12 years of experience designing lasers and microscopy systems for biological imaging to design new microscopes for the job.

In addition, the MIN funds a small number of pilot projects for faculty, in the form of facility access. A workshop series later this spring will cover some of these opportunities, as well as customized solutions that exist elsewhere on campus. Check the MIN website[5] for details.

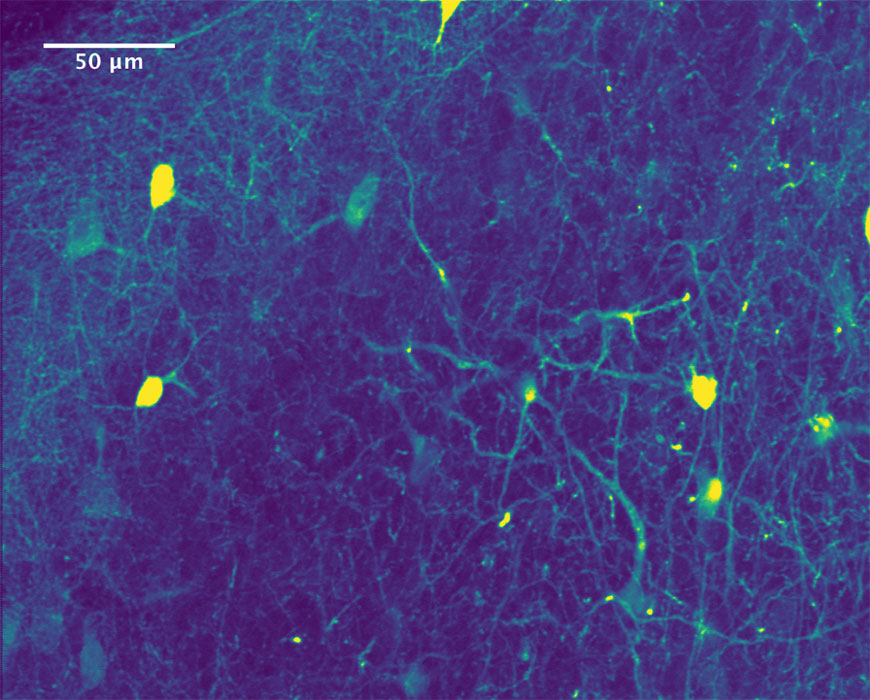

A two-photon fluorescence image of neurons in a mouse cortex. This image was taken with a microscope designed and built by MIN Director Jeff Field.

- CSU’s Microscope Imaging Network: https://vpr.colostate.edu/min/

- Foundational Core Facilities: https://vpr.colostate.edu/cores/foundational-core-facilities/

- Jeff Field: https://vpr.colostate.edu/min/min-team/

- new imaging techniques and instrumentation: http://source.colostate.edu/beating-the-limits-of-the-light-microscope-one-photon-at-a-time/

- Check the MIN website: https://vpr.colostate.edu/min/

Source URL: https://source.colostate.edu/exquisite-resolution-microscopes-illuminate-hidden-intracellular-worlds/

Copyright ©2024 SOURCE unless otherwise noted.