Editor’s note: Gabriella Gricius, a graduate fellow with the North American and Arctic Defense Security Network, and Ph.D. candidate in political science, Colorado State University, authored this piece for The Conversation in April 2022. Colorado State is a contributing institution to The Conversation, an independent collaboration between editors and academics that provides informed news analysis and commentary to the general public. See the entire list of contributing faculty and their articles here.

For the past quarter-century, the Arctic has been a unique zone of cooperation among the eight countries of the high north: Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Russia and the United States. Even when relations between Moscow and the West soured, the Arctic Council’s work was a reminder that multilateral partnerships could thrive despite global discord.

The point of the Arctic Council is to foster collaboration in areas such as scientific research, search and rescue operations and the challenges posed by climate change. Under its auspices, friends and adversaries alike – as well as nonstate actors, such as Indigenous groups – can sit down, talk and find common ground. In early 2022, lawmakers from Norway nominated the council for the Nobel Peace Prize for its collaborative spirit.

That collaboration ended shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022. One week after the start of the war, seven of the eight Arctic Council members announced that they would “pause” their work with the organization. Russia, which holds the council’s presidency through 2023, was left ostracized.

NOAA

The freeze of the Arctic Council is a loss on many fronts. As a scholar of Arctic security, I see cooperation in the region as essential to global security, and I believe an expanded set of institutions is needed to reflect new global realities as the Arctic warms.

Security and cooperation in the Arctic

The eight Arctic countries formed the Arctic Council in 1996. While the council explicitly steers clear of military issues, its members are stewards of the Arctic region. Unsurprisingly, the organization has grown in importance with global warming.

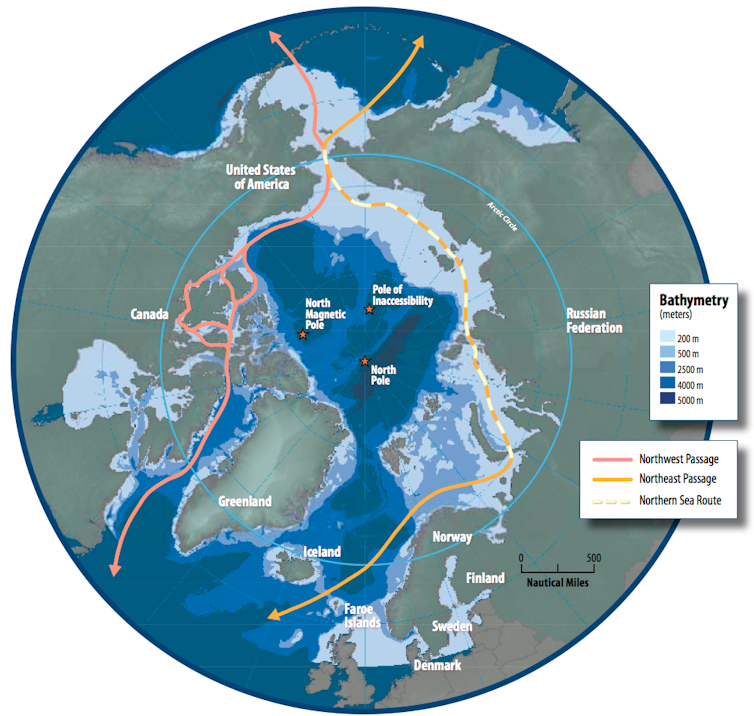

Warmer temperatures and declining sea ice are opening new shipping routes and, likely, expanding opportunities to exploit oil, gas and other critical minerals – changes that could spur conflict if not handled carefully.

Through the council, the Arctic states have made agreements related to search and rescue operations, oil pollution and scientific collaboration. The council has tracked environmental changes in the region with its yearly Arctic Climate Impact Assessment reports. Even when relations between East and West were at their worst, including in 2014 when Russia invaded and annexed the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine, joint endeavors in the Arctic remained strong.

Saul Loeb/Pool Photo via AP

Pausing the work of the Arctic Council was an understandable response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Yet in doing so, the other Arctic countries lost a valuable line of communication with Moscow. In time, it will be important to resume the council or establish a new institution in its place.

Indeed, working with Russia in the Arctic is even more important now than it was before the invasion. From a global security perspective, it is essential that the hot war in Europe be prevented from spilling over into the Arctic and one of the world’s last wildernesses.

The case for engaging Russia

Consider, for example, that while tensions are at an all-time high in Ukraine, it might be easy to mistake a flock of geese or a meteor shower for a military attack. Having a way for errors like these to be quickly remedied will be important in this new era of geopolitical competition.

Preserving and enhancing cooperation in the Arctic will take bold leadership. Some critics argue that institutionalizing military dialogue with Russia in the Arctic is an improper response to wanton aggression in Eastern Europe and could be seen as legitimizing Russia’s actions. These are valid concerns.

However, giving up on cooperation would be a mistake. The whole world will benefit if the high north can avoid the fate of militarization, a costly arms race and the terrible specter of war.

Maxime Popov/AFP via Getty Images

Ideally, engaging Russia within an expanded set of regional institutions – an invigorated Arctic Council, to be sure, but also a new military forum – would precipitate a cooperation spiral, increasing cooperation that could help lessen tensions elsewhere. Even if collaboration were confined to the Arctic, this would boost global security.

A new Arctic?

In the past, the Arctic states sought to maintain peace and stability in their region by divorcing contentious military issues from areas where common ground was easier to find. This has been the modus vivendi of the Arctic Council since its founding.

Going forward, it would be better to recognize that robust and ongoing cooperation is needed on security issues, too. Trust between Russia and the West might never return, but cooperation in the Arctic cannot be allowed to disappear with it.

[The Conversation’s Politics + Society editors pick need-to-know stories. Sign up for Politics Weekly.]![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.