Editor’s note: Steven Pressman, professor of economics at Colorado State University; Melanie G. Long, assistant professor of economics at The College of Wooster; and Veronika Dolar, assistant professor of economics at SUNY Old Westbury, wrote this article for The Conversation in January 2021. Colorado State is a contributing institution to The Conversation, an independent collaboration between editors and academics that provides informed news analysis and commentary to the general public. See the entire list of contributing faculty and their articles here.

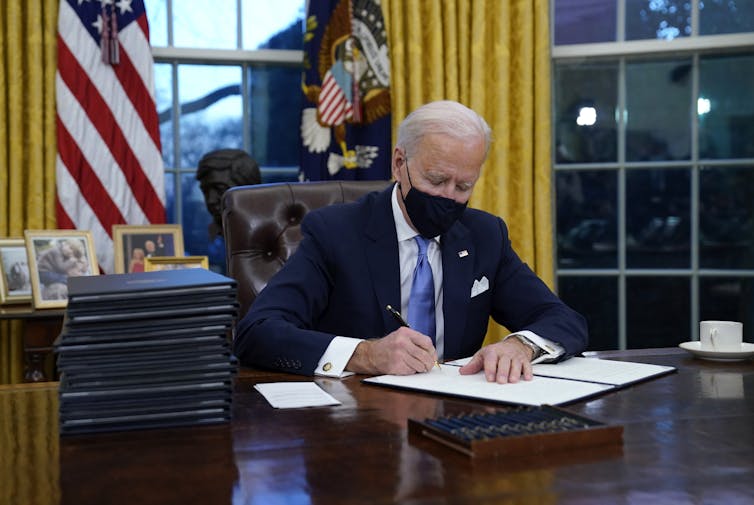

economic crisis. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

The Conversation editor’s note: The Biden administration has made it clear it wants to inject more money into the U.S. economy and provide more aid for priorities like vaccines, reopening schools and state governments. We asked three economists to share what’s on the top of their wish lists for Biden and Congress, and why.

A better way to save businesses while helping workers

Steven Pressman, Colorado State University

Since March, 20,000 U.S. businesses have failed every month, on average. Small companies, which employ nearly half of all workers, have been hit hardest. The U.S. economy will struggle to recover without significant support for small businesses and their workers.

One way Congress addressed these problems back in March is by offering small companies forgivable loans if they kept workers on their payroll for 10 weeks. While helpful, the Paycheck Protection Program came with major flaws, such as a design that led to lots of fraud. In addition, billions of dollars went to companies that didn’t need it, while some of those in greatest need couldn’t secure adequate funds.

The U.K. had a different solution. Its government created the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme, a form of wage and job insurance for workers. The government pays up to 80% of usual wages – subject to an income cap – to furloughed workers that companies retain as employees. Companies cover another 20% of usual wages. Low-income workers also receive additional monthly payments of up to the equivalent of about US$500.

Workers can be partially furloughed, working three or four days per week rather than five. This solves the problem of what to do about workers whose hours get cut or who go from full-time to part-time status.

The plan has helped companies reduce their labor costs, while maintaining flexibility to bring workers back when conditions allow. Importantly, aid goes to workers – not companies – which has ensured workers and their incomes have been protected throughout the crisis. And aid goes only to workers whose companies experience problems due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Unemployment rates in the two countries tell part of the British success story. In the U.K., unemployment increased gradually last year from 4% pre-pandemic to 4.9% in October. U.S. unemployment, in contrast, almost doubled from 3.5% to 6.7% in the that same period, peaking at nearly 15% in April.

The U.K. program has provided support to workers throughout the pandemic’s ups and downs. The Paycheck Protection Program was meant to be temporary, although more funds were added in December.

In the U.K., fraud has been limited because companies don’t get the money. And the government has encouraged workers to become whistleblowers, while imposing large penalties on the officers of companies engaged in fraud.

Rather than continuing to fund the Paycheck Protection Program, Congress and the president should switch gears and enact a program like the U.K.‘s that will see America through the crisis, however long it lasts.

Addressing the eviction crisis

Melanie Long, College of Wooster

The sharp rise in unemployment due to the pandemic has left many Americans struggling to pay the bills. Renters have been among the most vulnerable.

Compared with homeowners, renters are more likely to be poor, young and either Black or Hispanic – the exact same demographic of those who have suffered the most from the pandemic’s economic fallout.

The result has been a looming eviction crisis that has been staved off by a patchwork of federal, state and local moratoriums. Millions of renters could face homelessness once existing moratoriums expire and accumulated back rent comes due.

About 9 million households have fallen behind on rent payments, with over 1 million estimated to owe $5,000 or more. This could also worsen the public health situation and slow the economic recovery.

To address this crisis, I believe Congress needs to both provide short-term solutions and long-term fixes.

For starters, it’s vital that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s eviction moratorium continue. On Jan. 20, Biden extended the moratorium – which was set to expire at the end of January – to March 31. But that will likely need to be extended further.

Another critical need is rental and housing assistance. Biden’s proposed stimulus package already includes $30 million to help renters and support struggling landlords. Adding even more assistance could have major economic benefits as low-income beneficiaries especially are likely to spend every extra penny on food and other goods, stimulating the economy.

Access to affordable housing has been worsening for years, especially in communities of color. The gap between black and white homeownership rates has widened since the 1960s. The fact that only 42% of Black Americans own their homes, compared with 72% of their white peers, means most of them are renters, making them more vulnerable to losing their homes. It’s also largely to blame for the stark racial wealth gap in the U.S., which in turn reduces economic growth.

Congress could begin to address these deeper problems by providing down payment assistance in historically redlined communities, which would help households that are not currently on the edge of a financial cliff take advantage of historically low interest rates as so many others have.

MoMo Productions/DigitalVision via Getty Images

Helping women get back to work

Veronika Dolar, SUNY Old Westbury

During the pandemic, unemployment has been felt most acutely by women.

Women in the U.S. lost a total of 156,000 jobs in December, even as men gained 14,000. There were nearly 2.1 million fewer women in the labor force at the end of 2020 than there were pre-pandemic.

One reason for this is that women are more heavily represented in sectors that saw the biggest job losses in December, such as hospitality and private education. But another important one is that women generally have been expected to increase their already disproportionate share of household child care duties after COVID-19 shut down schools.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

All of this could lead to a significant decline in women’s total wages over time – one estimate puts it at $64.5 billion a year. This would result in a sharp drop in economic activity and billions in lost tax revenue for state and federal budgets.

But Congress could help offset this outcome in several ways.

One of the most critical is helping parents find affordable child care facilities. More than a quarter of child care centers in the U.S. remain closed because of the pandemic, and those that are open are often unaffordable. Child care costs have increased 47% during the pandemic.

Biden wants to address this by providing $25 billion to directly support child care providers and $15 billion to help low-income families afford care.

While this funding would go a long way to ensuring mothers have access to affordable child care, the lack of flexibility at most providers means women with uncertain work hours or who need other accommodations will still struggle. A more comprehensive plan should include some support to hire babysitters or even child support vouchers that could be spent as needed.

The other side of this issue is ensuring new mothers and fathers can take time off work to care for their children themselves. Biden’s proposal includes up to 14 weeks of paid family and medical leave, which will help ensure women don’t have to choose between a new baby and their career.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.