CSU’s Department of Soil and Crop Sciences has insights into the science of composting and how to do it effectively in a backyard setting.

If you’ve found yourself spending more time than usual in your garden while practicing social distancing at home, maybe it’s time to take on another project that both you and your plants can enjoy.

Composting can provide plants with nutrient-rich organic matter that supports growth while making use of food scraps that would otherwise end up in a landfill. But to avoid creating a monstrous pile of rotting food that neither you or your neighbors will appreciate, it’s worth learning how to compost properly.

Francesca Cotrufo and Addy Elliott, professors in Colorado State University’s Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, offered insight into the science of composting and how to do it effectively in a backyard setting.

Elliott teaches a composting course where her students learn what works and what doesn’t when trying to decompose organic matter. She compares composting to baking bread because the ratio between each ingredient is very important.

“You have to start with the right ratios,” Elliott, said, “and you have to follow the recipe.”

The composting recipe

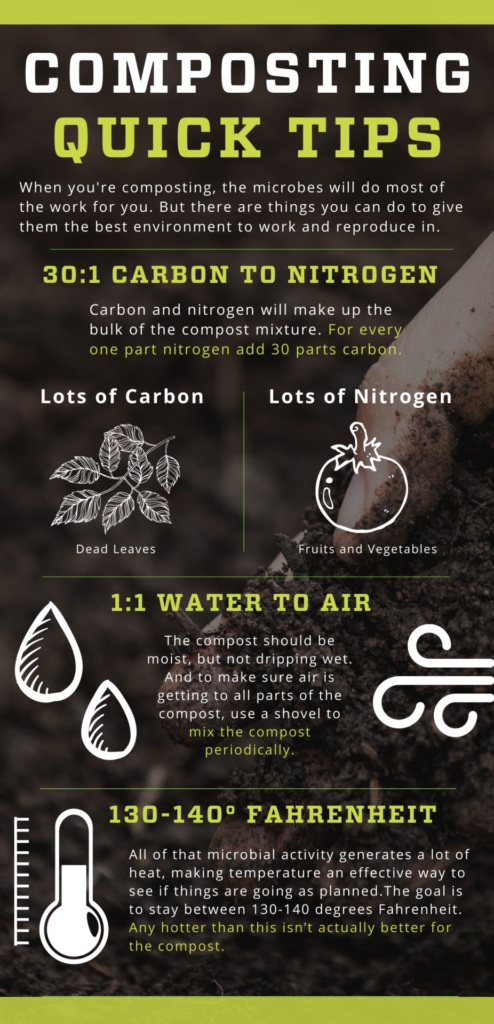

According to Elliott, the compost recipe contains four main ingredients: carbon, nitrogen, air and water. The ratios of each of these determine how abundant and how active microbes will be in breaking down organic residue, increasing their overall biomass and creating chemical structures that form quality compost.

Carbon and nitrogen make up the bulk of the compost mixture. For every one-part nitrogen, Elliott recommends adding 30 parts carbon.

“All food, whether it’s highly nitrogenous or it’s highly carbon-rich, has a little bit of both,” Elliott said.

So to get a carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of 30:1, it’s important to know the composition of the materials you’re adding. Food items that rot quickly, like fruits and vegetables, will contribute more nitrogen to the compost. Plant matter that’s dead and dried out, like leaves, hay or grass clippings, will mainly provide carbon for the microbes.

Cotrufo, who is a soil biogeochemist, said that you don’t have to be overly precise when combining the materials, as long as both carbon and nitrogen are represented in the mixture. Although, you’re welcome to get as scientific with the process as you like.

“Microbes need to be surrounded by residues that allow them to complete their chemical processes,” Cotrufo said. “For respiration, microbes need plenty of carbon while much of the nitrogen remains in the compost, creating a highly fertile end product.”

As for the other two ingredients — air and water — the ratio is a simple 1:1. The compost should be moist, but not dripping wet. In Colorado’s semi-arid climate, you will likely have to water your pile from time to time. And to make sure air is getting to all parts of the compost, Cotrufo recommends using a shovel to mix the compost periodically.

Sit back and let the microbes do the work

With your food scraps collected and leaves raked, it’s time to combine them to create a home where the decomposers can go to work. Elliott uses a box-shaped container made from pallets to hold the compost, and Cotrufo recommends having a lid to keep out raccoons or other animals. Cotrufo said she doesn’t compost meat residues — not because it’s bad for the compost — but because it attracts too many animals.

“Meat, cheese and bones are best kept out of a backyard pile,” Elliott said.

Whether you decide to buy a compost bin or build your own, you might have to experiment with what food to include depending on where you live and what animal friends you call neighbors.

Once you’ve combined the materials, the microbes will get busy reproducing and eating away at the food residue, converting it to compost. All of that microbial activity generates a lot of heat, making temperature an effective way to see if things are going as planned.

“Compost officially happens at, or above, 130 degrees Fahrenheit,” Elliott said. “This is where mesophilic organisms flourish. These are the microbes we ‘farm’ in composting.”

“Compost officially happens at, or above, 130 degrees Fahrenheit. This is where mesophilic organisms flourish. These are the microbes we ‘farm’ in composting.”

— Addy Elliott, professor in Department of Soil and Crop Sciences

The goal is to stay between 130-140 degrees Fahrenheit. Any hotter isn’t actually better for the compost, Elliott said. To reach this temperature range, you might have to adjust as you go, altering the quantities of each of the four main ingredients.

Using the compost

With patience, your compost pile will slowly develop a rich, soil-like consistency, but there’s no set time on how long this will take.

“If you’re an active composter, and you stop adding new material … you can have compost within three months,” Elliott said. “Of course, you can’t add things like avocado pits and orange peels and expect them to break down quite as quickly.”

Once your compost stops heating and breaks down into a more uniform material, it can be added to your landscaping to help plants grow by providing sources of nutrients that are easily available for them to use. It also increases the microbial diversity of the soil, something Elliott said increases the resilience of the plants you’re growing.

“I put my less finished compost at the base of my trees and other established perennials, and I put my nicest compost in my garden,” Elliott said. “So you don’t always have to have completely decomposed and fine-particled compost materials to use your product.”

Composting also serves the environment by keeping food scraps from going to the landfill, along with plastic bags filled with yard debris that are often sent there each fall. Landfills release greenhouse gasses like methane as organic residues break down whereas compost sequesters carbon, helping mitigate climate change, Cotrufo said.

Humans also can see direct benefits from this practice. Cotrufo believes having physical interactions with the natural world we depend on is an excellent way to promote mental health.

“Those of us who are fortunate to have a backyard and can garden — we can get food from it — but we can also rest our minds and release some tension,” Cotrufo said.