[masterslider id=”112″]

A new, low-lying building east of Moby Arena hasn’t gotten the same attention as some of the other construction projects on campus, but passersby may want to give it a closer look. It has not only given students in one of the most popular undergraduate majors at CSU a home, but contains uncommon craftsmanship and attention to detail.

The new teaching building for the Department of Health and Exercise Science opened this fall. The facility’s space is devoted primarily to a classroom and a teaching lab, but it also has a host of features that make it uniquely suited to the personality and objectives of the department that is home to the Human Performance Clinical/Research Lab, Adult Fitness Program, Heart Disease Prevention Program and Youth Sport Camps.

“We spent a lot of time talking about what they do and how we could support the department’s mission,” architect Art Hoy says, citing active lifestyles, openness and community outreach among the themes reflected in the structure. “The building has no back door. That was intentional — it has multiple fronts. A lot of times academic buildings are inwardly focused, and we decided to make it outwardly focused.”

Vitruvian Man

Vitruvian Man

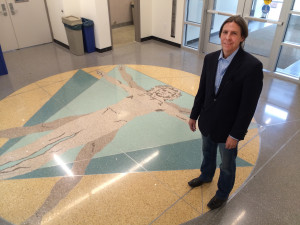

The hallmark piece of art is in the building’s central lobby. On the floor is an intricate terrazzo image of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. The seven-color concrete composite contains chips of rocks, broken bottles and seashells separated by thin bands of zinc. It is an ideal symbol for a department focused on health and exercise science: The celebration of the human body shows the outstretched arms and legs of one male figure touching the outline of a circle, while those of another figure touch a square. A commemorative coin will be placed in the navel — the exact center of the circle, square and entire building — during a dedication ceremony next spring.

“When the sun hits it, it really comes alive,” Hoy says of the artwork, which was created by Colorado Design and Tile.

The lobby’s ceiling is made with sustainably harvested bamboo; one wall contains a Brita hydration station. The 120-person classroom’s tables and chairs are on wheels, and four large computer screens on the side and back walls allow the space to be reconfigured for group work in pods. The teaching lab features large windows, and glass-paneled garage doors on the south side can be opened “to let the lab space flow freely out into the plaza and vice versa,” says Hoy, president of Denver-based AH Architecture.

Above the garage doors is a solar shade canopy made of metal bar grates and supported by a steel beam with decorative openings that can be used to support outdoor lab equipment.

“It also creates a kinetic light painting on the wall that changes minute by minute,” Hoy says.

The plaza

On the plaza are inscribed the words “Mobilitas aequat valetudinem,” which is Latin for “Movement equals health.” A band of colored concrete measuring exactly 50 meters stretches across the length of the plaza, interrupted only once by a zig-zag pattern that implies a heartbeat on a cardiogram.

“Every now and then you get to do something really special and meaningful, and this was one of those times,” Hoy says.

“Working with Art was a pleasure,” says HES Department Head Barry Braun. “He spent a lot of time with us, trying to understand what we do, and I think that’s reflected in the building in terms of movement, health and openness. He somehow managed to architecturally capture what we’re about.”

Hoy credits former Department Head Gay Israel with securing the funding needed to include the building’s various artistic touches.

“Gay’s commitment was to do this thing right and do it with quality and care,” he says. “That is seen in a lot of the details.”

Braun agrees.

“This is really Gay’s vision, and a testament to his drive and entrepreneurial attitude,” he says.

Israel, who led HES for 18 years before stepping down in 2014, says the department had no place to teach the lab sections in kinesiology, biomechanics and neurophysiology that other universities offer.

“It’s not just to keep up with other universities, but to get ahead, give our students a leg up,” Israel says. “It was the next natural thing we needed to do.”

Braun echoes those sentiments.

“We’re overhauling the curriculum, making it more forward-looking,” he says. “This facility helps us meet that goal.”

Cost sharing

The lion’s share of the project was funded with student fees from the University Facility Fee Advisory Board, which provided $1.2 million of the total $2 million price tag. The provost’s office contributed $250,000, the College of Health and Human Sciences gave $194,731, and the HES department covered the remaining $442,633, as well as an estimated $250,000 to furnish and equip the classroom and lab. A second floor could be added to the building, and there are still naming opportunities for prospective donors.

“The reality now is that sometimes you have to raise your own money for a teaching building,” Israel says. “You don’t whine about it, you just go get it done.”

The new facility also has symbolic meaning, since enrollment growth had forced HES to start using large classrooms in other departments’ buildings.

“This gives our students a home on campus,” Israel says.

“There’s a cohesiveness now,” Braun adds. “It brings the teaching, research and advising missions together in one place. When you have a family, it’s nice to have a home.”