According to a new study from the business schools at University of Colorado Boulder and Colorado State University, children consume more low-nutrition, high-calorie food such as cookies and candy after observing seemingly overweight cartoon characters.

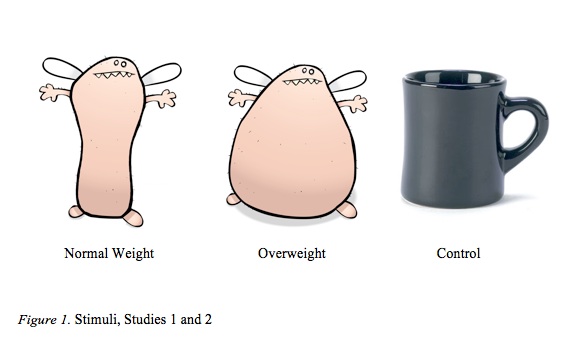

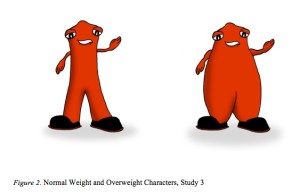

The results of the first-of-its-kind research indicate that kids respond to the apparent bodyweight of characters like the rotund, milkshake-loving Grimace formerly used to promote McDonald’s restaurants. Researchers sought to better understand physical stereotypes and their influence on children. They created their own character images for the study.

“Because research like this is new — looking at kids and stereotyping particularly of cartoon characters — we weren’t sure whether kids would be aware of bodyweight norms,” said Margaret C. Campbell, marketing professor at CU-Boulder’s Leeds School of Business and lead author of the study. “But surprisingly, they apply typically human standards to cartoon creatures — creatures for which there isn’t a real baseline. They have a tendency to eat almost twice as much indulgent food compared to kids who are exposed to perceived healthier-looking cartoon characters or no characters at all,” said Campbell.

Kenneth Manning, chair of the marketing department in the CSU College of Business; Bridget Leonard, a CU-Boulder graduate student at the time of the study and now assistant professor of marketing at Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne; and Hannah Manning, a CSU student, co-authored the paper, which is published online and forthcoming in the Journal of Consumer Psychology.

The study found that the tendency to eat more junk food after seeing a seemingly overweight cartoon character was curtailed when kids first had the opportunity to summon their previously learned health knowledge.

“This is key information we should continue to explore,” said Campbell. “Kids don’t necessarily draw upon previous knowledge when they’re making decisions. But perhaps if we’re able to help trigger their health knowledge just as they’re about to select lunch at school, for instance, they’ll choose the more nutritious foods.”

“This is key information we should continue to explore,” said Campbell. “Kids don’t necessarily draw upon previous knowledge when they’re making decisions. But perhaps if we’re able to help trigger their health knowledge just as they’re about to select lunch at school, for instance, they’ll choose the more nutritious foods.”

The findings — gathered across three studies from just over 300 participants ranging from 6 to 14 years old — have implications for marketers as well as parents navigating a world where children encounter cartoon characters in a variety of media, from books and graphic novels to TV shows and video games, movies and more.

“What I would like to see is companies being a lot more responsible with their own marketing choices,” said Campbell. “I think it is important for parents to know they should think about the way they might be associating food with fun for kids — in the form of exposure to cartoon characters, for instance — as opposed to associating food with nutrition and the family structure.”

The Kellogg’s brand is an example of a company that changed the image of one of its cartoon characters in a responsible way, she said. Several years ago, it revamped Tony the Tiger to be slimmer and more athletic, which may link the character with healthier eating ideas rather than to ideas of eating lots of sugary cereal.

The full study is available online.