On Oct. 28, 2011, NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration launched the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership, a satellite equipped with a sensor powerful enough to detect lights flickering in the most remote parts of Earth during the dead of night.

Dubbed the “Day/Night Band” for its illumination capabilities (most visible light sensors are only day bands) it was the first in a series of civilian low-light satellite sensors put into polar orbit. It also marked the start of a new era in nighttime environmental characterization.

Steven Miller, a senior research scientist and Deputy Director of the CSU-based Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere, leads the  team that is analyzing the sensor data and extracting useful information for a variety of research and operational purposes.

team that is analyzing the sensor data and extracting useful information for a variety of research and operational purposes.

He recently contributed an article to Scientific American highlighting the wealth of new information provided by this novel next-generation sensor.

For example, the Day/Night Band detected the eye of a tropical cyclone that formed last year near Hawaii and pinpointed its location far more accurately than conventional infrared sensors (of critical importance to forecasters as they attempt to better predict a storm’s path and if, when or where it will make landfall).

“Using moonlight reflection off the low-level clouds, we were able to peer through the high-level cirrus clouds and pinpoint the actual eye of the storm thanks to imagery from the Day/Night Band,” Miller said. “The infrared sensors only detected the upper portions of the storm, which in this case painted a very different and misleading picture of where the storm’s center was located.”

Researchers also were saw the human impacts of the devastation wreaked by the recent 7.8 magnitude earthquake in Nepal by comparing before and after images of city lights. The ‘after’ images showed the widespread power outages, particularly in smaller towns, caused by the earthquake.

We sat down with Dr. Miller and asked him about the research:

What makes the Day/Night Band sensor unique?

There’s an old church hymn that includes the famous words ‘…Was blind, but now I see!’

In a way, the Suomi NPP Day/Night Band has opened our eyes in ways that even the designers of this fantastic new sensor had not anticipated. In the simplest sense, conventional optical sensors used for satellite imaging are confined to infrared measurements at night, basically detecting things according to their temperature contrasts (for example, a cold cloud against the backdrop of a warmer underlying surface).

The Day/Night Band can use reflected moonlight to achieve this contrast—a fog layer with similar temperature to the surface that was once hard to detect is now seen plain as day with moonlight reflection as a bright cloud against a darker backdrop. The sensitivity of the Day/Night Band, reaching down to the faintest levels of moonlight and beyond, means that it’s basically a visible light sensor on steroids.

Is this the only Day/Night Band in use?

It’s the only one of its caliber. The sensors were actually developed by the U.S. military and they have used it on military satellites since the late 1960s—on the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program and its Operational Linescan System (OLS).

The Day/Night Band is the first low-light sensor to fly on a NOAA/NASA satellite system. It’s also the first time scientists have had ready access to calibrated data collected by one of these sensors in near real-time. The new Day/Night Band takes a technology developed at the dawn of the satellite era (an amazing advancement at that time) and updates it for the 21st century—with dramatically improved spatial resolution, precision, and sensitivity.

What have you seen with the sensor?

In the three and a half years since we’ve been examining Day/Night Band imagery, the question is rapidly transitioning from what have we seen to what haven’t we seen!

We’ve been able to detect all sorts of images and events. The nocturnal environment is replete with signals…some expected and some unanticipated.

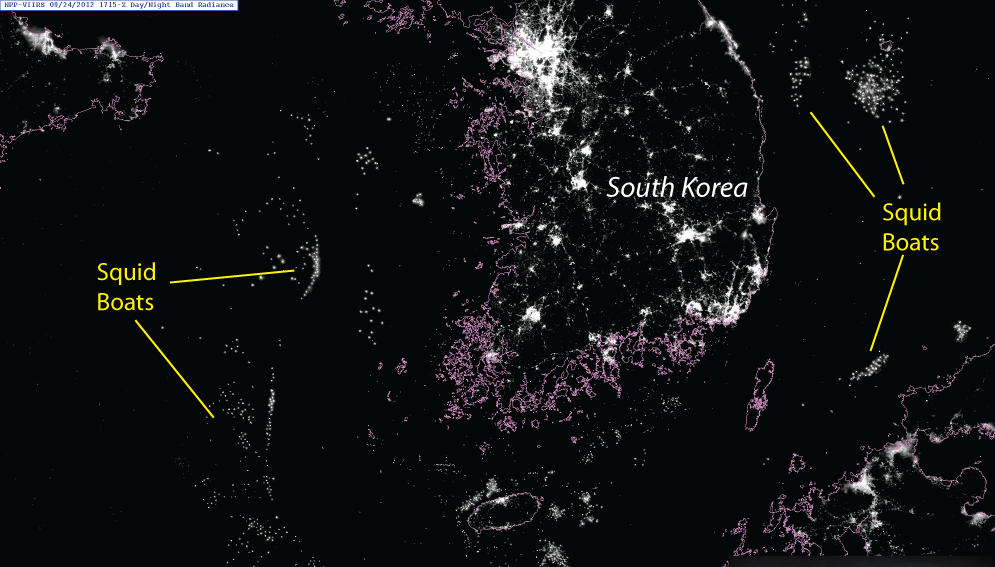

We knew we would be able to observe ship lights, but with the high spatial resolution (a single element of a Day/Night Band image is about 740 meters square…a factor of 50-100 times better than the OLS) we are seeing details of individual ship locations and are detecting interesting behaviors. For example, we see ships lining up at night along international borders which may be related to political posturing. We also saw a ship from the “Deadliest Catch,” which was caught along an ice shelf.

It can detect light from the natural gas well flares in North Dakota and shows the bands of light from our power systems.

Any surprises?

Absolutely, and the Day/Night Band continues to surprise. It’s such a fun sensor to work with because each new image is a veritable grab bag of fascinating and sometime unexpected information!

One of the biggest surprises, and a direct windfall of the sensor’s high sensitivity, is that the Day/Night Band can actually detect light sources emitted by the atmosphere itself (called airglow) on moonless nights. The implication is that there’s a kind of visible light imaging capability on every night—not just the ones when the moon happens to be up.

We thought we would need the reflection of the moonlight to see objects. But this natural light produced in the upper regions of the atmosphere provides us enough downward light to detect objects via reflection.

The upward component of this airglow is even more interesting to many scientists—we can often observe fluctuations caused by atmospheric motions that manifest as ripples of glowing air. These waves do eventually break, depositing their energy and driving the atmospheric circulation in ways that connect to all other parts of the atmosphere—it’s one big connected system!

The Day/Night Band is revealing a part of the atmospheric circulation that has been elusive, and has never been resolved at such detail. This is happening at exactly a time when our climate prediction models are trying to understand these dynamics—describing what goes on in the upper atmosphere is a key piece to the puzzle.

What is the next step for these sensors?

I share the opinion of many that when it comes to information, more is better, and it makes sense for these capabilities to be included on future geostationary satellites.

Right now, the value of the Day/Night Band is limited to the time when it comes across your area—meaning one time per night at around 1:30 a.m. local time (with some additional coverage as it moves toward high latitudes). The geostationary platform would allow the sensor to ‘hover’ over a specified location and provide regular and frequent updates of the changing lights over time…perhaps at resolutions of every five to 10 minutes or less for rapid scans.

Imagine… watching the meanderings of wildfires through remote forest valleys, the passing of ships in the night, pinpointing the locations of downed aircraft and other disasters which leave light signatures, detecting grid-scale power outages and power recovery, the ability to watch clouds and fog form and evolve, seeing the snow field left by a passive winter storm, and even watching the ripples of glowing atmosphere propagating away from thunderstorms, volcanic eruptions, and even tsunamis.

The possibilities are vast and so exciting!