July 28, 1997, was an unforgettable day in Colorado State University’s history. And given the coronavirus-related adversity the campus is currently overcoming, it’s a good day to revisit.

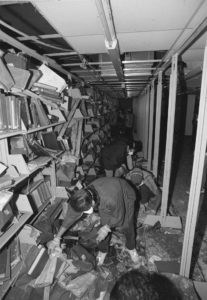

That was the day when 31 hours of intense rainfall on the west side of Fort Collins resulted in serious flooding on campus. The waters caused more than $140 million in damage, with the Lory Student Center, Eddy Hall and Morgan Library hardest hit. Almost a half million books were damaged, and the first floor of Eddy was inundated. The Oval became a pond.

There is a lot of video from the 1997 flood, from TV news reports to footage from on-campus videographers, and some of that footage will be included in film producer Frank Boring’s documentary on the history of CSU, in honor of its 150th birthday.

A call from campus

Patrick Burns, chief information officer of the CSU System, was a professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the time. He got a call at home around 11 p.m. from one of his graduate students, who was working in an office in the lower level of the Engineering Building.

“He said, ‘There’s a lot of water coming up through the drain,’” Burns recalled. “He asked if he should shut down the UNIX systems, and I said, ‘No, get the hell out of there!’”

Burns said the student headed east and saw water backing up almost to the height of the railroad tracks at the pedestrian underpass near the Glenn Morris Fieldhouse. The next day, Burns and a couple of his students snuck onto the closed campus to squeegee four inches of water out of his grad student’s office.

“All the nasty stuff in the drains and sewers came up,” he said. “You couldn’t just dry stuff out, because it was corrosive and toxic.”

Floating pages

He also remembered watching the news at home that night and seeing footage of five feet of dirty water at the CSU Bookstore, where the glue on book bindings dissolved, setting free millions of pages from textbooks that had just come in for the fall 1987 semester

“A few big brown trout also came out with the pages,” he recalled with a laugh.

Computer servers in the E Wing of the Engineering Building came within an inch of being inundated, Burns said, and faculty with offices on the first level of Eddy suffered severe losses. He remembers the Morgan Library’s losses vividly as well; faculty on campus were queried to see what books and journals they might have to replace those that were lost.

Burns, who went on to serve as dean of libraries and vice president for information technology, pointed out that the natural disaster prompted the creation of the Rapid InterLibrary Loan (RapidILL) service, which was developed by CSU Libraries staff to borrow volumes to refill the empty shelves. It grew into a system for efficient peer-to-peer sharing and electronic document delivery for libraries globally. The system became widely used by other universities and libraries, and was later sold.

All of the buildings on the Oval sustained significant damage, but the insurance coverage only paid for putting those buildings back into their pre-flood condition. Fortunately, CSU President Al Yates successfully lobbied for funding from the state legislature to bring those buildings up to modern standards for their facilities, classrooms and IT infrastructure. This modernization was a huge boon to the occupants of those buildings, and has stood them in good stead through today.

Impact on the admissions office

Vice President for Diversity Mary Ontiveros was working in Spruce Hall at the time of the flood, in the admissions office. She recalls that the lower level of the building had a bunch of that year’s recruitment materials, and much of it was lost when the water came in. She recalls a staff member frantically unplugging anything that had an electrical cord, and prospective students with their families requesting campus tours despite the natural disaster.

At the time, the campus bakery and meat lab were based in Johnson Hall and what is now Centennial Hall (then the Administrative Annex), and Ontiveros remembers seeing flour and meat mixing in the floodwaters there. The water coming up through the drains was like “sludge,” she recalled.

Chris Seng, special assistant to the vice president for enrollment and access, added that Housing & Dining Services stored dry foods and frozen meat in the lower level of the Annex, and when the floodwater moved east from the Lory Student Center and Oval, it backed up when it hit the railroad berm.

“Talk about a disgusting mess, with all of that frozen meat and water,” he said. “There was a smell too.”

‘Who needs help?’

When asked about the recovery effort, he said it was similar to what is happening on campus today.

“It was like the spirit is now,” Seng said. “People were saying, ‘What can we do to help? Who needs help to be ready to go for the fall semester?’”

Ontiveros said musical instruments were piled on the Oval in front of what was then the music building, now the home of The Institute for Learning and Teaching.

She was taking a pottery class in the lower level of the Lory Student Center at the time.

“My work was in there, but it was pretty bad, so I hoped that it was lost,” Ontiveros remembered with a laugh. “But it was all saved.”

Losses at CTV

Greg Luft, head of the Department of Journalism and Media Communication, was faculty advisor to the campus television station CTV at the time. He recalled seeing aerial footage of the flooded areas on TV and a window well at his home filling up with water. He ended up working with news organizations that gathered near the mobile homes where four fatalities occurred, as the flood made national news.

When Luft was allowed back on campus after the flood, he visited the CTV offices on the north side of the Lory Student Center and found a mess.

When Luft was allowed back on campus after the flood, he visited the CTV offices on the north side of the Lory Student Center and found a mess.

“Everything was washed up against the north wall,” Luft said. “There was mud and water on the floor, and all of the electronics were full of mud. Everything that was electronic was gone.”

Saving student media

He said the water level in the basement of the Bookstore reached two-thirds of the way to the ceiling, and he has a vivid memory of watching crews tossing all of CTV’s damaged furniture and equipment in huge garbage containers. Later that fall, the CBS Denver television station KCNC provided a truckload of old equipment to CTV, and “saved CTV for the fall semester,” Luft said. The student-run station, KCSU-FM, and the Rocky Mountain Collegian newsroom moved into the bus barn on the east side of what is now the University Center for the Arts. Student Joel Smith worked with journalism faculty member Pete Seel to make a short documentary about the flood.

He added that the words of Yates provided some inspiration for the recovery.

“He said we would use the flood as an inspiration to build a greater university,” Luft said. “Those immediately affected were kind of devastated, but we had to get ready for the return of the students. President Yates said that we have a semester to get ready for, so everybody buckled down, dove in and made it happen. For student media, it was really rough, but it brought everybody together. It was a crazy time, kind of like it is right now.”

Reel CSU Stories

This is part of a series about the stories uncovered by film producer Frank Boring and audiovisual presentation specialist Bryan Rayburn, who are going through CSU’s film archives to compile a documentary about the University’s first 150 years. For more stories, an interactive photo slider and a quiz on CSU lore, visit csu150.colostate.edu. For an in-depth look at how the colleges of CSU have carried on the land-grant mission through the decades, go to source.colostate.edu/csu-150.