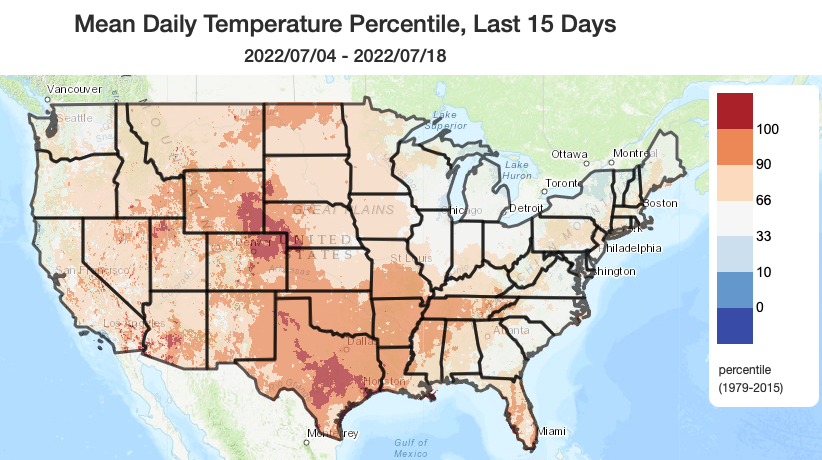

This map courtesy Climate Mapper shows the percentile ranking for temperature across the U.S. over a 15 day period in July.

With nearly a third of the U.S. facing excessive heat warnings and the U.K. coming off of a stretch of record high temperatures, weather is dominating headlines around the world.

“It’s becoming almost routine to see records like this every summer,” said Russ Schumacher, Colorado’s state climatologist and the director of the Colorado Climate Center at Colorado State University. “It’s not great, but it’s the reality that we’re coming to live in.”

He took some time to talk to SOURCE about climate change, the science behind the record heat and the outlook for the rest of the year in Colorado and beyond.

Tell me about the climate situation in Colorado, and what makes this different from the average July.

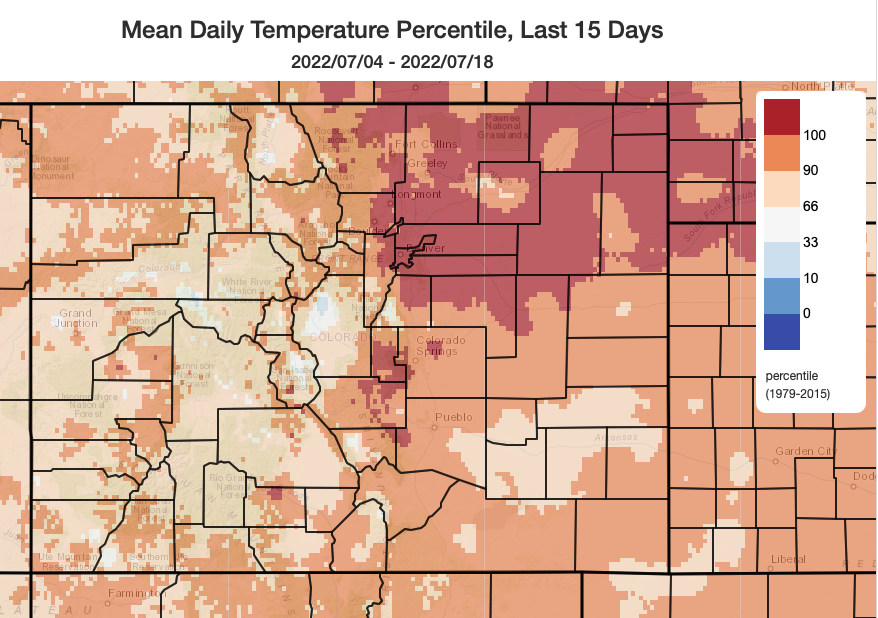

This is the time of year when we are often at our hottest, typically, but the last week or so – and really, July as a whole – has been much hotter than average, especially in the Eastern Plains, where the drought situation is worsening with the record heat and lack of rain.

Russ Schumacher is the director of the Colorado Climate Center and the Colorado State climatologist.

It has big impacts on agriculture in eastern Colorado. When it gets hotter, that makes everything worse, putting stress on crops and water resources and rivers.

What’s the science behind what is causing the record heat?

The short version is, we have this big ridge of high pressure that’s retaining heat over much of the central and southern U.S., which isn’t unusual to see happen in the middle of the summer.

However, these typical midsummer conditions are getting taken up a level due to the fact the climate is warming.

So, what would’ve been a more typical heat wave in the past is becoming more intense and lasting longer, and all of these impacts are starting to emerge – not just in the U.S., but around the world, including the recent record heat in the U.K.

How this comes out in a climate change context is the weather is always changing, and you can have a hot day or a cold day still, even in this changing climate, but we’re seeing a lot more record heat than record cold.

There are many studies coming out now showing that these extreme heat waves like the one in the Pacific Northwest last summer and the one in Europe right now would not be reaching the level they are reaching in terms of temperatures without the changing climate.

Beyond the phenomenon of climate change, is there anything else linking the record heat in the U.S. to the U.K.?

We’ve been in La Niña conditions for the past two years, and it looks like it could persist for a third year. La Niña years are warm and dry, especially in places like eastern Colorado, Oklahoma and Texas.

El Niño and La Niña are the variations that happen in water temperatures in the Pacific Ocean. That affects where jet streams tend to go, which affects the weather even far from the Pacific. In Colorado, La Niña years tend to be drier than average, especially in spring, summer and fall.

The jet stream affects the weather, and during La Niña, what tends to happen is the northern states are wetter, the southern states are drier.

Is it true that in some respects, conditions like this haven’t happened in the U.S. since the Dust Bowl?

When you look at the record books for extended periods of hot conditions in the central United States, the years that pop out are in the mid-1930s, which was the Dust Bowl era, the mid-1950s, and now several recent years.

In Colorado, 2002, 2012, 2020 and 2022 are all showing up for years where we had extreme heat in different parts of the state. What it shows is that in areas already prone to hot and dry conditions, records are coming more frequently.

Those years you mentioned were particularly bad for wildfires in Colorado. What’s the outlook for later this summer and in the fall?

The good news we’ve had this summer is that there have been pretty active monsoon rains in the mountains. I think that has helped temper the fire danger a bit, but that’s not to say we can’t still get a big wildfire this year.

In 2020, the fires didn’t get started until August, but the rain has been more active in the mountains this year, which has been good for the wildfire situation. And we’ve also unfortunately seen deadly flash flooding on the burn scars from previous fires again this year.

The Eastern Plains have been feeling the brunt of the heat wave in Colorado, rather than the mountains, and the outlooks so far point to the monsoon being fairly active, so I’m hopeful that fire danger is not as bad as it’s been in past years.

A map courtesy Climate Mapper depicting Colorado temperatures by percentile across Colorado over a 15 day period in July.

What do you think people should talk about more when it comes to the recent record heat?

I think when it comes to drought conditions, we should be focusing on the impacts on the farmers in Eastern Colorado extending into Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. It will have a real impact on the food we get and everything else that comes with that.

Also, while 100-degree temperatures aren’t that uncommon in parts of the U.S., it’s very unusual in the U.K. and is shattering records by a large margin. Those places aren’t built for high heat, there’s no air conditioning, and the infrastructure wasn’t built to withstand it.

Heat is also one of those insidious things. It’s one of the biggest weather-related killers, but it’s not something you can see visually, like a tornado that comes in and leaves a path of destruction, or the rising waters that come with a flood.

What’s the weather outlook looking like for the rest of the year?

In the near-term, it’s going to continue to be hot. In Colorado, we’re going to get some relief from the heat in the next week, but it will still remain quite warm.

We’re tilted toward drier conditions and drought, and it’s likely to continue because of the continuation of La Niña.

The atmosphere can always surprise us, of course, but that’s the indication I have.