There’s an old football term known as a dual-threat quarterback, referring to the once-rare phenomenon of a quarterback who not only threw the football well but could create positive plays with his legs. In the art world, Monique Crine is just that.

The Denver-based artist spoke at length about her work on Sept. 17 as part of the lecture series connected to the CSU University Art Museum’s current exhibition “Scrimmage: Football in American Art from the Civil War to the Present.” “Scrimmage” gives an in-depth look at the American relationship with its favorite sport and its portrayal in art in the 19th and 20th centuries. Crine recently concluded her solo exhibition, “Critical Focus,” at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Denver, an exhibition that focused on her most recent project, “Eden Prairie,” a series of paintings portraying retired football players.

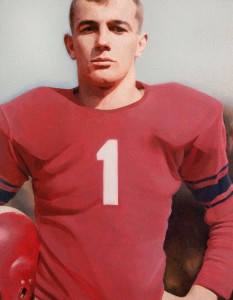

Influenced by mid-century American film, and her grandfather Leslie Crine – a press photographer in the 1960s – Crine’s paintings, typically oil on canvas and based upon photographs taken by Crine herself, capture a realism rarely seen in such a medium. As an avid film photographer who still works with 35mm film and her grandfather’s camera, Crine uses her talents as both an accomplished photographer and an award-winning painter to create this stunning and life-like work.

But it is not simply creating paintings of the photographs that makes her work so captivating. Crine looks for what she calls “cinematic perspective” in her paintings, displaying many pieces in larger-than-life size and scale with ratios commonly associated with film and cinema, giving her work a widescreen or landscape display and feel to them.

The film influences don’t end there. With the meticulous detail, Crine can take up to weeks or sometimes even months translating the film to paint, incorporating elements such as distortions of light – like lens flares – and texture captured only in analogue film and the inherent “flaws” representative of the medium.

So why paint something that has already been photographed?

“Painting from the photographs gives [the paintings] a quality of realness that you can’t find in film,” said Crine. “The textures, the lights, things come out of the painting … that can’t be seen on the film.”

That’s where the magic really begins. Crine finds a converging road between two mediums often seen as separate and unequal.

Now on her sixth series of hyper-real paintings, Crine, whose subjects revolve around iconic American imagery, takes her large, cinematic art style to tackle larger-than-life figures, noting with a smile: “There’s nothing quite as American as football.”

Crine acknowledges her ignorance about the sport when she began the project, but that didn’t diminish her captivation with her subjects.

“When I started this project, I didn’t know anything about football, but I was drawn to these larger-than-life, literally, figures,” she said.

Crine’s focus is retired players (retirement often due to injury) and their post-football journey. She expected the personalities of these athletes to match the intensity and ferocity of the figures she saw on the field, but Crine was amazed at the humble and gentle giants she encountered.

“I was surprised, getting to meet many of these players and hear their stories, they were all very kind, and gentle, and absolutely nothing you would expect,” she said. “They’re gladiators, they’re absolute spectacles.”

Crine’s next project features the first generation of black football players in the Southeastern Conference.

Crine’s painting “Richard, 1961” a painting of her father based upon her grandfather’s photograph, and part of her series “Wooden Nickels” are on display in “Scrimmage” at the University Art Museum in the University Center for the Arts through Dec.18. The museum is open Tuesday through Saturday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.