It’s the most wonderful time of the year to photograph snow crystals, which is why Steven Fassnacht can be found in his backyard in below-freezing weather.

“My spouse, she just kind of shakes her head, ‘cuz I’m outside in the morning and it’s -5˚C, -10˚C [23˚F, 14˚F] and I’m in my dressing gown and slippers taking pictures,” said Fassnacht, a Colorado State University professor of ecosystem science and sustainability who studies snow hydrology.

He’s interested in the shape of the snow crystals, not just for their beauty, but to understand how the snow crystals form, fall and ultimately contribute to our water supply.

“I drink my glass of water and most of this started off as that [snow],” he explained, holding up a glass of water as if in tribute to the miracle of how the two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms organize themselves in every drop (or crystal).

In arid Colorado, water is stored, pumped, measured and fought over as a precious resource for agricultural and urban areas alike, which is why modeling and measuring it accurately is so important.

In his research, Fassnacht uses remote sensing technologies (like radar and satellites) to try to measure water in the atmosphere and on the ground.

“As it’s falling, how do we measure it?” he asked, with the curiosity of a child. “Then, how does it change, and how does it add into the water that’s in the river?”

Fasnacht encourages his students to not only consider the data from these technologies but to engage with their research completely.

“All those tools [remote sensing technologies] are getting better and better, but we still need to go out there and be amongst the medium,” he believes. “You need to touch it. You need to feel it. You need to taste it. You need to have that connection to see what’s actually happening.”

How snow crystals get their shape

The shape of a snow crystal tells a story of how it came to the earth.

“Water is a mineral. And the nature of it, the angle within the water molecule changes – that’s one of the really cool things,” said Fassnacht. “In solid form, ice is actually in this matrix, this lattice, that has six sides.”

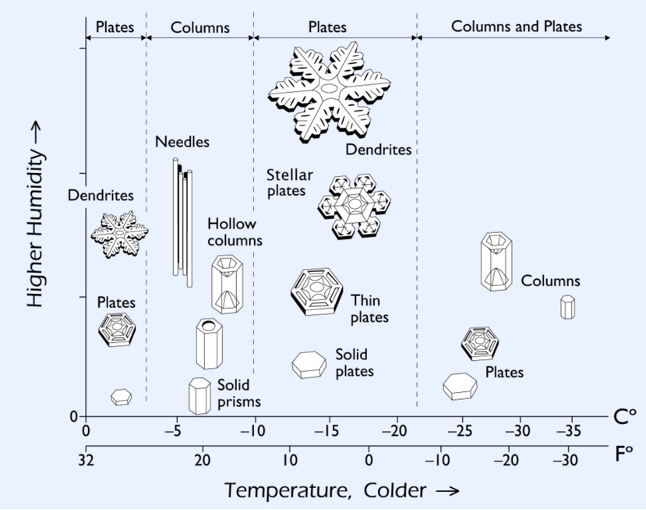

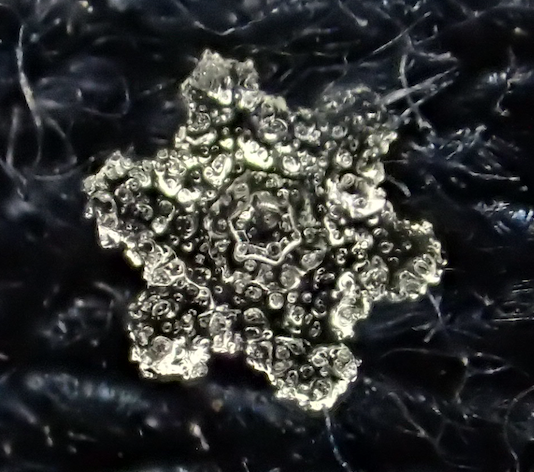

Snow crystals are always six-sided because of the lattice formed by the specific spacing between each molecule when freezing. Whether the crystal grows out in a long, thin needle or a flat star shape (called a stellar) has to do with temperature and the amount of moisture in the air.

The crystal will grow as it falls through the atmosphere as long as the air is supersaturated with water. Layers of colder temperatures will encourage a star, while slightly warmer layers (still colder than freezing) will make needles. This is why every snowflake is unique: No two snowflakes fall through exactly the same temperatures and moisture levels in cloud layers. (But one snowflake enthusiast has grown identical twin snowflakes in a lab.)

Art and science

As Fassnacht sees it, the problem is that even with radar and satellite data, we still don’t know exactly what’s happening in the cloud or the atmosphere below. The shape of the snow crystal can give us some idea.

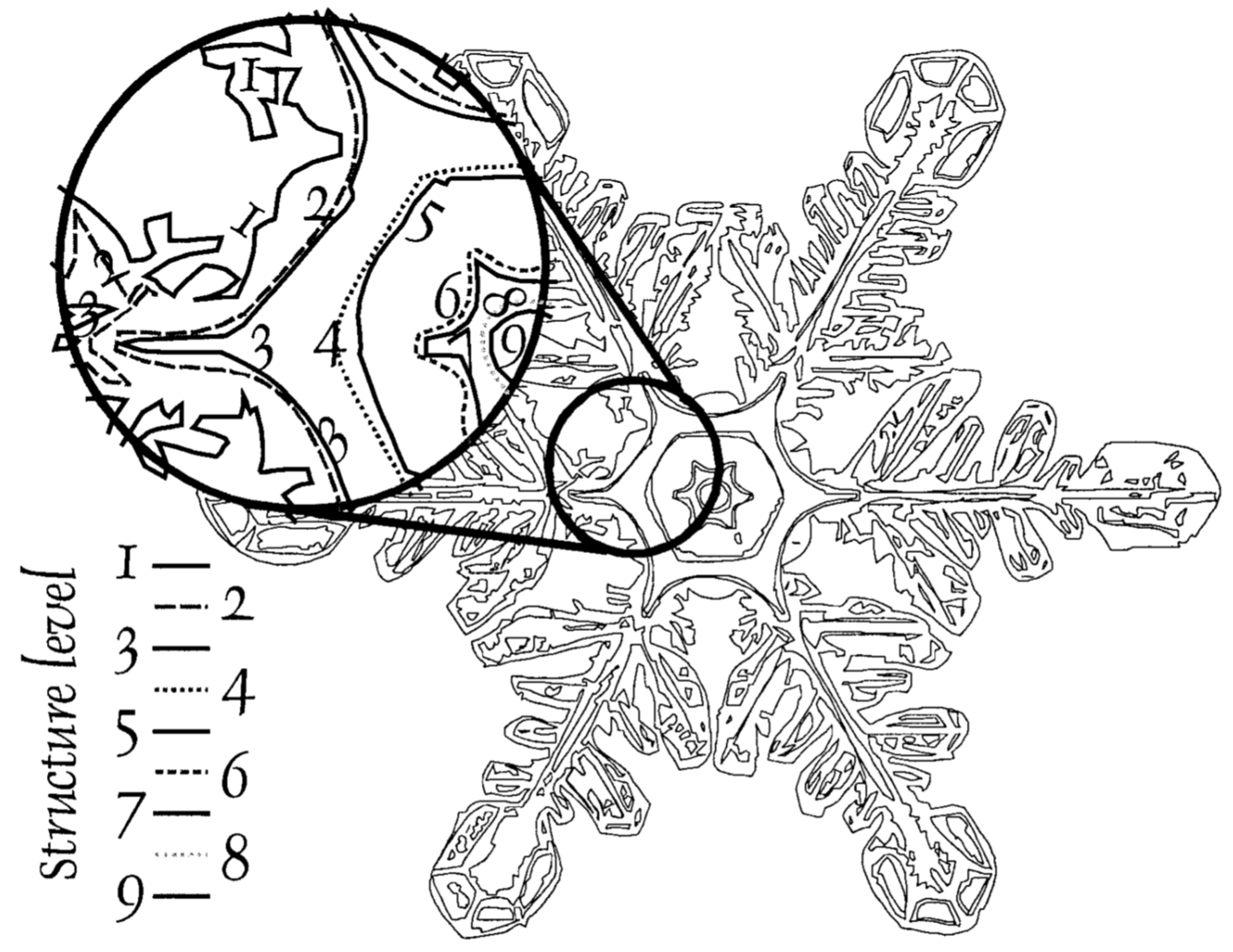

His melding of art and science began in graduate school, where he designed an algorithm to convert a photograph of a snow crystal into quantifiable data.

“We were able to take the images, scan them, turn them into data, come up with some statistics from the literature to actually do an assessment, sensitivity analysis, etc.” he said.

Lately, Fassnacht has been photographing frost because “the shapes are fascinating,” and current climate, snow, and water models do not represent frost well.

When he’s not in his dressing gown and slippers taking photographs, he’s working with local schools to champion scientific outreach through art. Fassnacht encourages students of all ages to think about water through not only visual art but written art, too.

“It’s a meshing between water as metaphor and having the students experience nature and think about literature,” he said.

He’s developed modules for high schoolers taking U.S. Literature and is working to convert these to the middle school level. Last year he worked with the Colorado Water Center encouraging kids to write water poetry.

How to photograph a snow crystal

Some of the best snow crystal photography was done in the late 1800s by Wilson Bentley. Fassnacht used Bentley’s snow crystal images to scan and analyze in graduate school.

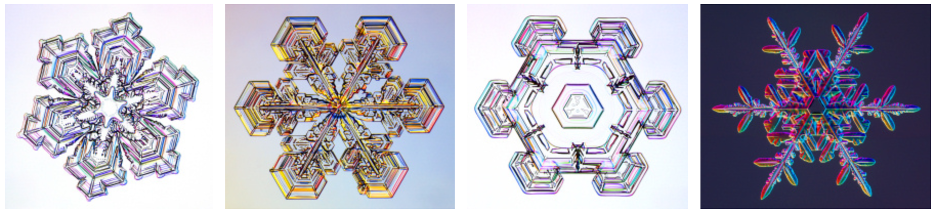

Dr. Kenneth Libbrecht, a physics professor and modern snow crystal expert at CalTech, has set up a lab to grow (and photograph) snow crystals.

“I have an Olympus, just a little point-and-click, that has a really good zoom and macro [lens],” said Fassnacht.

After hearing how easy it could be, I headed outside during the last snowfall to try and create some art of my own. The verdict? There are definitely some tricks. A macro lens (or two, one stacked on the other) is crucial. Snowflakes melt incredibly quickly and are best seen in contrast against a dark (and sufficiently cooled) background. My hair did a pretty nice job of catching this one.