An NIH-funded clinical trial testing the efficacy of a physical activity educational program for middle-aged and older adults was one of hundreds to face serious disruptions this past year.

As they say in show business, the show must go on. The same is true for Colorado State University’s $407 million research enterprise, comprising thousands of faculty, staff and students making cutting-edge discoveries every day in the life sciences, physical sciences and social sciences, as well as scholarly pursuits in the humanities and visual and performing arts.

Last March, a campus normally humming with students, shoulder-to-shoulder in labs, studios, classrooms and dining halls, went into sleep mode when President Joyce McConnell ordered classes to go virtual, and nearly all campus operations – including research labs and field campaigns – moved to virtual settings where possible.

As students prepared to leave campus and not return after spring break, faculty, staff and emergency managers reckoned with a burgeoning pandemic, staring down the possibility of not setting foot in an academic building for weeks or months. Touchy instrumentation was carefully powered down, and 3D printers went home to garages. And Zoom and Teams expertise skyrocketed, as anything that could move online, including lab meetings and publication-writing collaborations, did.

Video to showcase researchers looking back on the pandemic year

A new video featuring 19 researchers will provide a look back at the COVID-19 pandemic on the first anniversary of Gov. Jared Polis’ statewide Stay at Home order, March 26, 2020.

Action in a Time of Crisis was produced by videographer Ron Bend of the CSU Social and Digital Media Team and is sponsored by the Office of the Vice President for Research. The public is invited to its debut on March 26 from 1-2 p.m. via Zoom.

“It is hard to overstate the impact of the disruptions, from a scientific standpoint,” said Christa Johnson, associate vice president in the Office of the Vice President for Research. “If someone couldn’t continue to work on a project, their entire career could be disrupted. Even now, it’s really hard to estimate the long-term impacts.”

The federal government did make room for adjustments to normal grant activities in light of the pandemic, Johnson said. Federal agencies allowed universities to continue charging people’s time to existing grants, whether work was getting done or not. The university also received CARES Act funding to offset some of the initial operational burdens.

Work, interrupted

Even so, work came to a grinding halt, at times derailing years of carefully mapped-out research. Manfred Diehl, University Distinguished Professor in Human Development and Family Studies, was in year 3 of a five-year, National Institutes of Health-funded randomized controlled trial on March 23, the day campus stood still. Colorado Gov. Jared Polis issued the statewide stay-at-home order three days later. Diehl’s clinical trial examines the efficacy of a CSU-developed educational program called AgingPLUS, aimed at motivating middle-aged and older adults to become physically active on a regular basis.

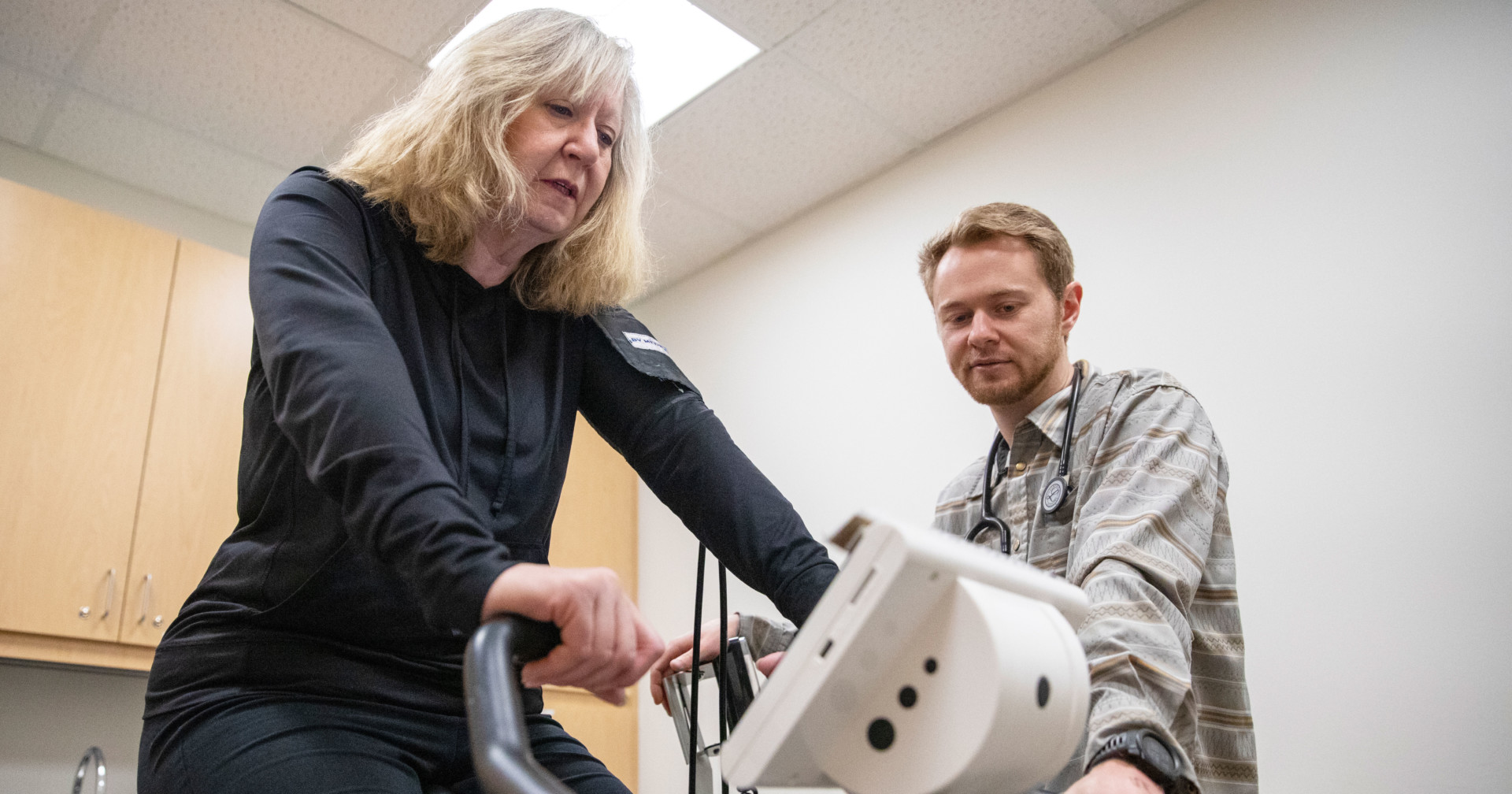

University Distinguished Professor Manfred Diehl’s clinical trial is several months behind schedule for data collection, due to the pandemic. These photos were taken before the research program was moved to virtual settings.

At the time, Diehl’s research team had tested about 168 individuals, with a target sample size of 320. Each study participant is usually enrolled for eight months, with various assessments, interventions and follow-ups. The stay-at-home orders created a slew of logistical problems by delaying data collection and interrupting the flow of planned research, Diehl said.

Effectively closed down until mid-July, the team is now about six months behind schedule in terms of data collection. And, despite implementing strict safety protocols, the team has had trouble recruiting new participants during the pandemic.

“Currently, we are testing study participants and just started new intervention groups. Of course, everything has to be done at a reduced capacity because of COVID-19 requirements,” Diehl said.

The breadth of impacts has been enormous and difficult to measure. Field campaigns, like a multi-university National Science Foundation-funded atmospheric science project in Taiwan called PRECIP, had been slated to begin this past summer but was postponed until 2022. The Office of the Vice President for Research worked to categorize different research programs as green, yellow or red – red being, “’holy cow. We’re not sure what we are going to do without completely subsidizing this project,’” Johnson said.

For many, the stress of suddenly having to teach online, close down their lab spaces with compassion and empathy, and tend to the needs of their own families as well as their students, took its toll. But the CSU research community did anything but lie down and wait.

The community’s response

For example, until the COVID-19 pandemic changed life as we know it, a small group of cancer survivors would head to a CSU lab each week for a research-based group exercise program called Fit Cancer, aimed at building physical and emotional strength for participants.

Last March, the Fit Cancer program, like hundreds of others, had to quickly adapt to a world of limited or non-existent in-person interactions. Those enrolled in last year’s program were forced to withdraw, unable to complete their post-program assessments.

Pressing through these challenges, the Fit Cancer staff moved the program online, starting with four participants in the fall 2020 semester. They now have 40 participants, with plans for more.

“We have been able to reach many more cancer survivors with the virtual program,” said Heather Leach, program director and assistant professor in the Department of Health and Exercise Science. “We currently have a wait list of 87 individuals for our summer and fall cohorts, which will also be delivered virtually.”

The Fit Cancer program moved online and continued to collect data on its participants, who are all cancer survivors.

Both researchers and participants adjusted to new realities. Participants were encouraged to join Zoom sessions early just to talk, according to program coordinator and doctoral student Mary Crisafio. “Some participants have exchanged contact information to communicate outside the program, so they’ve gained a nationwide support system through our program that wouldn’t have been possible had it only been offered in-person.”

What’s more, last March marked the start of an unusual increase in research activity at CSU compared with previous years, according to Doug Leavell, director of research analytics in the Office of the Vice President for Research.

Research activity increased

In April 2020, roughly a month into the pandemic, CSU researchers requested $171.1 million in research funding from various entities, including federal and state sponsors, compared with $97.8 million in April 2019 – a 75% increase. Researchers sought review of 259 proposals, compared with 172 the previous April. The uptick in research activity was attributable, in large part, to the research community jumping into action and devising ways to contribute their time and expertise to pandemic-related projects.

Through the pandemic, there emerged an entire category of scientists, including but not limited to infectious disease researchers, working in areas producing important pandemic-related insights. There was the team led by Ray Goodrich, director of CSU’s Infectious Disease Research Center, who got to work right away on a vaccine candidate called SolaVAX ™ that repurposes a commercial platform used to inactivate pathogens in blood transfusions.

There was clinical pathologist Gregg Dean, head of the Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Pathology, who is using a genetically modified form of a common probiotic as a possible vaccine against the novel coronavirus.

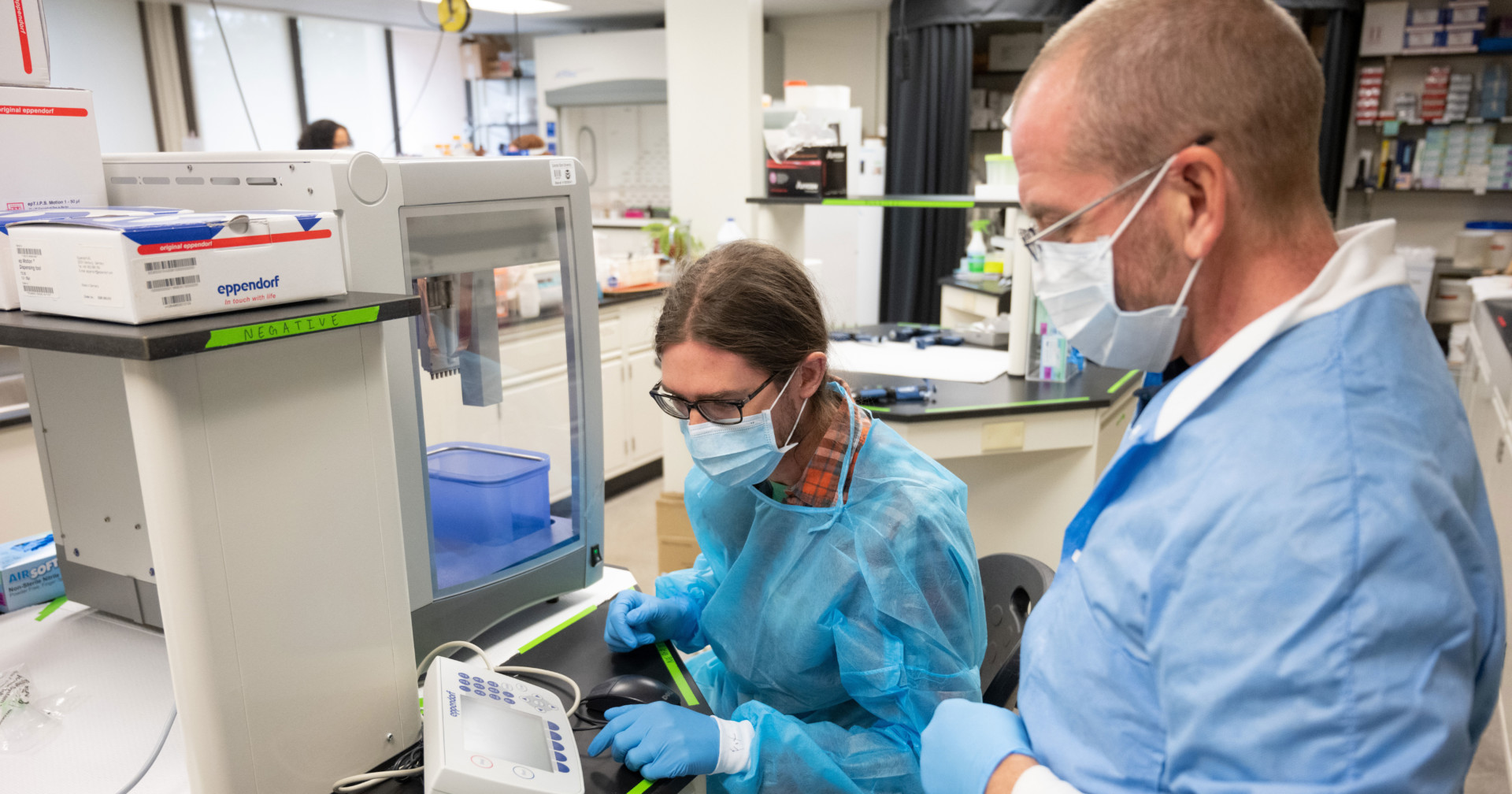

There was the team led by veterinarian and professor of surgical oncology Nicole Ehrhart, director of the Columbine Health Systems Center for Health Aging at CSU, who launched a statewide COVID-19 surveillance testing project for workers at skilled nursing facilities.

Others, like assistant professor Jude Bayham in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, had expertise in pandemic modeling pre-COVID, and was tapped for a state of Colorado public health modeling team.

And there were professors Carol Wilusz in microbiology and Susan De Long in civil engineering, who combined their expertise to create a wastewater testing program to help the state and CSU see outbreaks before they happen.

“I think the urgency, the immediacy, of needing solutions during the pandemic gave people unique perspective on the important of science and technology for answering questions,” said Heather Pidcoke, the university’s chief medical research officer. “One consistent theme has been this overwhelming sense of gratitude at being able to be part of the solution, which I think is really meaningful.”

To date, CSU researchers have requested $86 million in proposed COVID-related research funding, with $21.1 million and counting so far obligated to the university, according to the Office of the Vice President for Research.

The early days

As much as CSU has world-class experts in infectious disease, virology, microbiology and many other fields touching the immediacy of the pandemic, its research and scholarship landscape is vast, from life sciences to engineering to music, theater and dance. When the pandemic forced shutdowns of physics, biology and engineering labs, visual arts studios and performance venues, it was up to key leaders in departments and colleges to help guide those slowdown processes, and as quickly as possible, ramp back up.

Sonia Kreidenweis, research associate dean in the Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering, remembers with clarity the day CSU Health Network executive director Lori Lynn spoke to Dean David McLean’s leadership team about needing to revamp the college’s emergency plan, as global headlines spelled a worsening pandemic. “It felt very academic and abstract at the time,” Kreidenweis said. “But as things accelerated, and we were told, ‘The labs needs to be shut down this week,’ it came as a total shock.”

With just a few days to notify faculty, staff and students that research operations would be suspended, the college leadership team began prioritizing which programs could be quickly powered down or moved online. And they had to decide which programs would have special permission to keep running at limited capacities, so that years of data collection wouldn’t be lost, or sensitive equipment wouldn’t be irreparably damaged.

Department heads were the first line of communication, along with the college’s executive committee. Kreidenweis and the other research associate deans served as liaisons to central university teams responsible for managing pandemic response, such as the Pandemic Preparedness Team, and joined the Research Continuity and Recovery Working Group, which runs out of the Office of the Vice President for Research and continues to meet regularly.

President McConnell formed the research continuity working group in spring 2020, then chaired by Professor Sue VandeWoude, which included Vice President for Research Alan Rudolph, Associate Vice President for Research Johnson, Warner College of Natural Resources Dean John Hayes, and Dean McLean. The large group of faculty and staff implemented an evaluation process developed by Cory Hudson in Research Services that helped rapidly assess which groups of researchers were ready to return to campus.

“Faculty and students have been wonderful,” Kreidenweis said. “They have been grateful to have access to their campus facilities to continue their research, and for the guidance in how to manage operations with public health as the primary consideration. They have taken safety very seriously.”

Returning to on-campus work required researchers to develop plans for reduced capacity, social distancing and other public health measures.

Before researchers could come back to work on campus, they were required to have approved plans that would include personal protective equipment, social distancing and other sanitation and public health guidelines. In the Scott Bioengineering Building, where lab spaces are often shared, faculty created pod leaders and a virtual scheduler so that different researchers could use time and space equitably, while keeping buildings at the 50% or less approved capacity.

“I can’t say enough about how much everybody has pulled together to help each other continue progress on ongoing research projects, especially for graduate students who were wrapping up thesis and dissertation work,” Kreidenweis said.

During the initial ramp-down phase last spring, College of Natural Sciences Research Associate Dean Melissa Reynolds began a spreadsheet outlining every lab’s critical functions and whether they could be done remotely. The list of exceptions was long. There were the nematodes, lab animals and transgenic plants that required routine maintenance. There was the laser lab that could suffer damage to its ultrastable cavity if left unchecked. In the chemistry and biochemistry labs, there were cryogens that needed liquid nitrogen replenishment to keep cells from dying, and for the maintenance of delicate chemicals. And on top of that, there were a handful of projects with direct COVID applications prioritized to keep working through the pandemic.

Like Kreidenweis, Reynolds worked with faculty to identify research that needed to be maintained during the initial suspension.

“The biggest difference between pre-pandemic and now is that people need to plan and schedule rather than just showing up and then deciding what to do,” said Reynolds, who has chaired the Research Continuity and Recovery Working Group since July. “This is a major culture shift for many research programs.”

Shift for students

It’s been an especially difficult shift for students, who were used to coming in, hanging out, and building community through serendipity. “Students have set times they can be in the lab, which requires much more pre-planning. This has caused some anxiety,” Reynolds said.

Shutting down campus operations and ramping back up became an unexpected part of the job description for Ken Quintana, CSU emergency manager and part of the university’s Pandemic Preparedness Team. In the early days, Quintana visited dozens of lab, classroom and academic spaces, helping building managers and staff set up six-foot distancing measures, and assisting department chairs and instructors to operate as safely as possible.

Particularly challenging were some spaces in the visual arts buildings, where students typically move about freely in workspaces and share tight quarters. And just last month, Quintana’s team was called out to an equine reproduction lab to help set up public-health protocols for students doing clinical rotations.

Quintana is no stranger to emergencies – he’s been with CSU since he graduated with an environmental health degree in 1993, and he worked on campus when the historic 1997 flood washed out several campus buildings.

“What I’ve told people is that we don’t have a code book. We don’t have regulations that tell us exactly what to do,” Quintana said of what COVID-19 has wrought. “All we have are best practices, the tools in our toolboxes. We all just have to be flexible.”