The first time Georgia Granger was struck by the powerful effect that animals can have on people was more than 40 years ago, when she was feeling sad.

“I was crying on my living room floor, and my four dogs surrounded me,” she recalls. “That’s when I started thinking about the human-animal bond.”

There have been many more examples since then, from her mother preferring the presence of dogs over people while recovering from a stroke to the powerful effect a dog’s presence can have on hardened former gang members in counseling.

Early bonding

While living in Tennessee, Granger started attending meetings of the Delta Society, now known as Pet Partners. She was so inspired by one of the group’s founders, veterinarian Leo Bustad, that she developed her own organization dedicated to animal-assisted therapy.

Granger began building Human-Animal Bond in Tennessee (HABIT) in 1985 while her husband Ben was dean of the College of Social Work at the University of Tennessee. When Ben was hired to lead what was then CSU’s Department of Social Work in 1992, Georgia brought the nonprofit to Colorado State, renaming it Human-Animal Bond in Colorado (HABIC).

Ben, who passed away in January 2015, served as co-director of HABIC, but it was really Georgia’s baby from the start. “I had no idea it would grow like it did,” Georgia Granger says. “I haven’t been able meet the demand these last few years. But the passion has only increased over time. What we’re doing is too good to stop.”

Ben, who passed away in January 2015, served as co-director of HABIC, but it was really Georgia’s baby from the start. “I had no idea it would grow like it did,” Georgia Granger says. “I haven’t been able meet the demand these last few years. But the passion has only increased over time. What we’re doing is too good to stop.”

In the program, HABIC-certified, animal-assisted therapy dogs (and even a couple of cats) work with professional therapists on customized treatment protocols that address challenges as varied as head trauma, elder issues and autism. HABIC is run under the umbrella of the School of Social Work in the College of Health and Human Sciences and currently operates 63 distinct programs staffed by about 150 human-animal teams.

The dogs visit nursing homes, respite care facilities, rehab clinics, mental health facilities, hospitals, youth correctional facilities, treatment centers for eating disorders and Veterans Affairs facilities — from Denver to Fort Collins, Estes Park to Greeley. Granger says HABIC is also active in 36 public schools, working with at-risk kids who are referred by a teacher, counselor or psychologist in cases involving everything from bullying to attention-deficit disorder to autism and Asperger’s syndrome.

Some of the most impressive experiences have occurred at the Platte Valley Youth Services Center in Greeley, a secure-custody facility for long-term sentenced/committed youth ages 10 to 21. Granger says even the most rough-and-tough youth soften and open up during individualized HABIC sessions with the trained dogs.

Some of the most impressive experiences have occurred at the Platte Valley Youth Services Center in Greeley, a secure-custody facility for long-term sentenced/committed youth ages 10 to 21. Granger says even the most rough-and-tough youth soften and open up during individualized HABIC sessions with the trained dogs.

“It’s amazing how the dogs can change their attitudes,” she says. “They’ll break down and cry and talk more because the dog is there. They begin to trust you, and they’ll talk while petting the dogs. It makes it more likely for the counselors to hear things they’ve never heard before.”

‘Calmer state’

Anthony McAlister, a certified addiction counselor at Platte Valley who has used HABIC dogs for about a decade, agrees. “Clients tend to lower their defenses, because they’re not just speaking with a human; an animal is present,” he says. “They get in a relaxed, calmer state. They’re not as guarded as they would normally be.”

McAlister says the dogs’ mere presence in the facility has a positive effect on all who see them, and he’s started incorporating the animals into a new group therapy session.

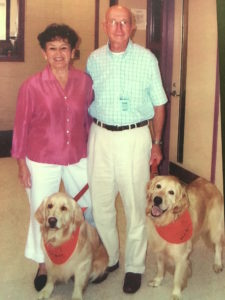

Georgia Granger, second from left, started her first human-animal bond program more than 30 years ago.

One time, McAlister made a breakthrough with a client who had been heavily into gang activity — and had been at Platte Valley for about two years without much progress.

“We realized that he’d never had the opportunity to be a child and play,” McAlister recalls. “So we set aside time in the session for him to roll around on the floor with the dog and just be a little kid.” The client has since gone on to college and a successful career.

Granger says the dogs are taught commands that clients can replicate, which is rewarding.

Granger says the dogs are taught commands that clients can replicate, which is rewarding.

“When the dog does what they ask, they are so proud,” she says. “They feel good having that attention and learning the commands. A lot of people say our dogs are magic.”

Visits to terminally ill people in hospice can be incredibly moving.

“They’ll ask the dog to take them to heaven,” Granger says. “They’ll talk to the dog about unresolved issues they don’t want to discuss with staff or family. It is really powerful.”

The preparation

The preparation

There is an extensive four-month orientation, training and evaluation process for people and their dogs to achieve one of two levels of HABIC certification and begin volunteering. A veterinarian performs a medical examination and behavioral screening to determine the dog’s suitability for the job.

“It’s the dedication and commitment of our volunteers that make it so great,” Granger says of the success of the program, which is funded by donations and a nominal fee for its services. “We touch the lives of about 700 people each week.”

As she reflects on HABIC’s legacy, she pets her golden retriever Shilo, her eighth dog that has served in the program. The two are about to make another trip to Platte Valley that afternoon.

As she reflects on HABIC’s legacy, she pets her golden retriever Shilo, her eighth dog that has served in the program. The two are about to make another trip to Platte Valley that afternoon.

“He is the sweetest, the most calm, and the most thoughtful,” Granger says of Shilo. “We are a good team.”

“I believe in HABIC 100 percent,” McAlister says, adding that there aren’t enough teams to accommodate demand at Platte Valley. “If I could have a HABIC team for every client, it would definitely be a benefit.”

For more information or to learn how to volunteer, visit www.habic.chhs.colostate.edu. To support HABIC, visit https://advancing.colostate.edu/HABIC.