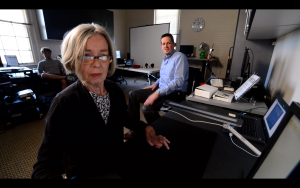

Betty Svendsen sits in front of a computer on the third floor of Colorado State University’s Occupational Therapy Building moving her partially paralyzed left hand side to side as fast as she can. The 67-year-old stroke survivor is trying to slice watermelon and lemons as they fall from the sky in a video game.

Behind her, Matt Malcolm, a professor of in the Department of Occupational Therapy, and Tara Klinedinst, one of his graduate students, watch her movements and level of concentration.

Svendsen’s gaze never wavers. She is determined to beat her high score.

“I don’t like to lose,” she said. “I’m very competitive.”

When she finishes, Malcolm and Klinedinst review the data collected by the motion-sensing controller and the game. Svendsen does, in fact, set a new record. But even more importantly, she moved her left hand faster and further than in previous games and her response time and accuracy at hacking fruit also improved.

Those are good signs for the occupational therapists.

It means Svendsen is regaining many of the hand-eye coordination skills she lost when she suffered a severe stroke on August 8, 2008 and seems more aware of her left hand. It also indicates that GATOR (Games and Assistive Technologies for Rehabilitation) an online therapy tool for stroke victims they’ve been developing with Sudeep Pasricha, a professor of in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, is working for Svendsen.

“Betty’s range of motion and her response time is improving and she also appears to be more aware of her left side, which was affected her stroke,” Malcolm said. “These are all things GATOR is designed to do.”

The need for GATOR

A stroke occurs when blood flow to the brain is suddenly interrupted. Deprived of oxygen-carrying blood and other nutrients, brain cells die off, causing significant damage for those who live.

Of the 700,000-plus people in the United States who suffer strokes each year, approximately two-thirds survive and require rehabilitation to help them regain or relearn skills lost when the brain was damaged. The aftermath can result in paralysis or lack of control over movements; memory and cognitive issues; emotional changes; trouble speaking or understanding language and other problems.

Rehabilitation can take months – and even years. Many experts agree that repetition and practice are important elements for stroke survivors to regain everyday skills such as combing their hair or brushing their teeth or learn new ways of completing everyday tasks.

But getting patients to practice at home can be difficult. And it’s also tricky for therapists to monitor how much patients are doing outside of their in-person sessions.

“It’s very hard for therapists to monitor what patients are doing at home, the progress they’re making and if activities need to be adjusted,” Malcolm said. “A lot of people don’t want to practice when they get home or do the activities assigned by their therapists and they really need in order to improve their skills and quality of life.”

GATOR addresses these issues by allowing a therapist to remotely monitor practice sessions, check a patient’s progress and also adjust a game to make it harder or easier. The games are designed to be fun and engaging for patients while also encouraging them to improve their range of motion and awareness of their weaker side.

The online, Internet-based system also is accessible to people who live in rural areas or don’t have ready access to an occupational therapist. It also relies on low-cost, off –the-shelf components such as a LEAP motion sensor that retails for $79.99.

“The system is designed to be an accessible, low-cost tool for stroke survivors,” Pasricha said.

Collaborating across colleges

Pasricha, a computer engineer, first approached Malcolm about the project in 2011. He had read about some of the constraints surrounding occupational therapy for stroke victims – many require years of intensive, expensive therapy – and was interested in using augmented reality games as a tool.

“It’s important for these patients to do therapy at home and the games seemed like a way to make it more interesting and interactive,” he said.

Malcolm was intrigued. He also was interested in developing technological tools but didn’t have the computer coding or gaming background to do it.

“There are a lot of benefits to this type of system and as a therapist, you want to design an in-home program that your patients will actually do,” he said.

The two have collaborated on the project since, cobbling together resources to develop GATOR. Several teams of engineering students have worked on it for their senior design projects and several students in CSU’s occupational therapy also have participated.

Pasricha and his students have spent much of the past few years working with Malcolm to understand the effects having a stroke has on the brain and body, the intense rehabilitation patients undergo and the activities occupational therapies use to help victims regain basic skills.

For example, the games force users to increase their range of motion and also recognize and use the side of their body weakened by a stroke. (Depending on the side of the brain a stroke damages, survivors often lose control of one side of their body. They tend to rely on their stronger side so much the other deteriorates further. )

The project also had to be user friendly for therapists and provide them with specific data about a patient’s movement, including range of motion and accuracy. Pasricha and his students have re-programmed the motion sensor to report that data, which feeds into the scoring for the game.

“We’ve spent a lot of time learning about strokes and the activities occupational therapists use to help them,” said Michael Rowack, who graduates in May with a bachelor’s degree in computer engineering. “Having that knowledge has helped us design better games for patients and therapists.”

Putting GATOR to the test

After four years, GATOR project is now in beta testing. Malcolm and Klinedinst have worked with local physicians to recruit stroke victims like Svendsen who are willing to test the games and participate in the study.

The CSU team plans to use the data to refine the games and apply for funding to test it more widely.

Having stroke survivors use GATOR has already yielded critical information – and new games.

Pasricha’s engineering students have attended several of the beta testing sessions to watch how the patients interact with GATOR. That has led them to not only improve existing games but also develop new ones.

For example, after watching Svendsen try to unfurl her left hand and stretch her fingers, Chris Hesser, a senior majoring in computer engineering, returned to Pasricha’s lab and developed a game specifically to help with that. The game displays hand movements that stroke survivors like Svendsen imitate using the LEAP sensor. The goal is to force them to open their hand and stretch their fingers.

“It seemed like something that would help Betty and others and none of the games we had incorporated those motions,” Hesser said.

Initial results from the beta testing are promising. During Svendsen’s recent round of gaming in March – when she achieved a new high score – she remarked several times that she felt more aware of her left side.

She also believes the games have helped her regain some of the dexterity and agility she lost during the stroke. She credits GATOR with much of that and tells a story about how recently, she caught an egg before it rolled off her kitchen counter.

“I haven’t been able to do that since [before] my stroke,” Svendsen said. “I was able to recognize what was happening and react to it.”

Malcolm and Pasricha are heartened by Svendsen’s improvements and results from the beta testing. But, they caution, more testing is needed. Still, they believe one day, GATOR will become a useful tool for therapists and stroke patients alike.

“Our project has been very successful in bridging the gap between engineering, clinical rehabilitation, and computer science, to create an innovative cyber-physical system involving humans closely interacting with technology to improve their lives” Pasricha said. “Through this project, we hope to make low-cost in-home upper limb rehabilitation a reality for millions of stroke patients around the world”.