For firefighters, communication is a matter of life and death. This is a fact that Timothy Amidon understands better than most.

An assistant professor in the Department of English, Amidon’s background includes over 15 years of experience in the fire service as a firefighter and officer with Westerly Fire Department in Rhode Island, a fire instructor with the Rhode Island Fire Academy, and a technician with Rhode Island Search and Rescue. In a culture where there are thinkers and there are doers, sometimes with little apparent overlap, he occupies the intersection between academics and firefighting, and has devoted his academic research to understanding and improving firefighter communication.

As a captivated audience looked on at the College of Liberal Arts Great Conversations speaker series last week, Amidon engaged them in a discussion about cultivating communication in the world of firefighting.

Firefighter literacies

Many assume that literacy is simply the ability to read and write. But Amidon explained that in the world of firefighting, literacy involves other forms of interpretation and communication.

“Firefighters are some of the smartest people I know,” Amidon explained.

When assessing and entering a burning structure, firefighters use all of their literacies — visual, tactile, kinesthetic, aural, verbal, and radio — to evaluate the situation and communicate within the team in an organized, efficient effort. They must visually read the smoke, understand the structure, and evaluate the progress of the fire. If a firefighter is unable to correctly interpret fire behavior and communicate important information back to the rest of the team, the situation can quickly escalate to danger.

Understanding radio communication — often over a static-filled signal and in the midst of the sound of the roaring fire — takes a high level of skill. Firefighters must learn how to use aural and radio literacy to rapidly process and prioritize such communications in a high-stress environment. In a word, firefighting communication is complicated.

When communication fails

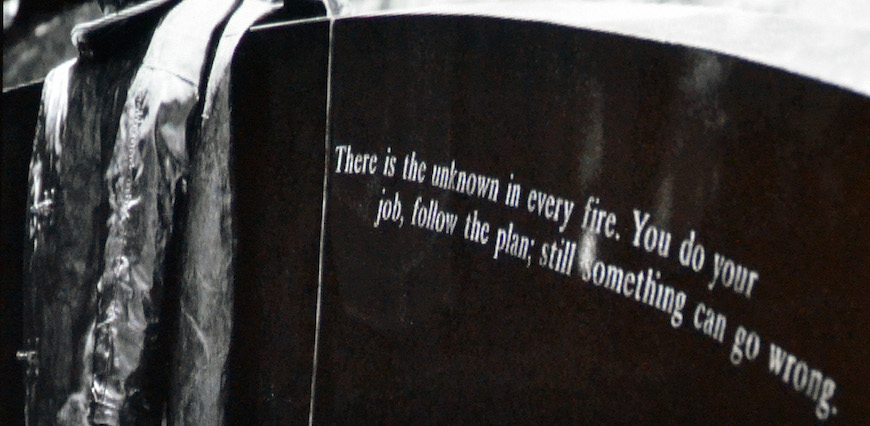

Amidon went on to show that sometimes communication breaks down — and the consequences can be fatal. One hundred firefighters die each year in the line of duty, and many more are seriously injured. Structural and equipment issues can play a role in these casualties, but communication problems are a factor that is often overlooked or misunderstood.

Amidon pointed to three fires to highlight the tragic ways in which communications can go awry: the Memphis Pilgrims Hope Baptist Church and Indianapolis Athletic Club fires in 1992, and the 1995 Mary Pang Frozen Chinese Food Warehouse fire in Seattle. In these incidents, eight firefighters and one civilian lost their lives, and 10 firefighters were seriously injured.

Though the official causes of death varied, communication difficulties played a significant role in each of these fires. In some cases there were problems with equipment, including malfunctioning technology and radios that could not be operated while wearing personal protective gear. But human factors tied to how firefighters interpreted and communicated about the situation were also contributing factors.

In one case, two separate fires were accidentally assigned to the same radio channel, interrupting critical communications. A new communications system has recently been implemented but staff had not been adequately trained.

Additionally, Amidon pointed to a 1999 United States Fire Administration (USFA) report that suggested firefighters may be reluctant to circumvent the chain of command to make progress reports to the incident commander. The report also found that firefighters are well prepared with manual skills, including how to operate equipment and strength-building. However, less is being done to prepare them to communicate effectively under pressure.

Yet another complicating factor is that firefighters don’t always have equipment necessary to communicate. Far too often, lower-ranking firefighters are not equipped with radios, leaving them voiceless and unable to transmit a mayday if they needed to.

Lapses or misunderstanding in communication in these three tragedies meant that the incident commanders did not receive information that would have provided a big picture of the fire, and impacted their ability to make strategic decisions about how to best control the fires while keeping firefighters working on scene safe. This led to confusion and disorganization, and ultimately cost some firefighters their lives.

Culture of bravery

One of the biggest challenges in improving fire service communications is that it requires confronting firefighting culture.

According to Amidon, mainstream culture does not link hand and brain. This leads to value being placed on manual skills in firefighting with less emphasis on the communications skills that are equally life-saving. Additionally, the culture of bravery in the fire service means firefighters might not want to admit they are having a problem.

Amidon argues that there is a lot of value in training firefighters as leaders and thinkers. While specialization is crucial in firefighting as it allows in-depth focus on different parts of a complex problem, it is also essential that firefighters of all ranks be able to effectively evaluate and communicate risk situations.

Amidon explained that the most qualified team member to lead a rescue isn’t always in the leadership position, which can result in trust issues and communication breakdowns.

“It’s important for the incident commander to trust the rescue technician because the technical knowledge associated with different rescue disciplines is so specialized,” he said. “But sometimes commanders aren’t comfortable with relinquishing power to team leaders, which can pose problems.”

Throwing the red ball

To illustrate the creative ways that firefighters might intervene to do what is best for patients while working within the chain of command, Amidon shared a story told by a team of technical rescuers during a research interview.

“A car went over a steep embankment and an occupant was trapped inside. The rescue company began planning the best way to perform a rope rescue. However, a chief arrived who was uncomfortable with rope rescue, because his knowledge of the discipline was not as current as the team members who train on it regularly. Based on prior experiences the team had developed a strategy for dealing with these types of complicated power relations. They had a code phrase, ‘throw the red ball,’ that they would use to signal to a member of the team that they needed to distract the incident commander so the team could carry out the task quickly and safely without interference.”

Amidon noted that this example illustrates a communication and hierarchy problem that needs to be addressed further.

“It’s important to work within the chain of command, but part of that means ensuring that we’re following standards and empowering the most educated technicians to make the types of operational decisions they’ve been qualified to make,” he said. “It’s dangerous for those with more institutional power but less operational and technical knowledge to make command decisions about which rescue systems are best in a given situation. Ultimately, for me, it comes down to if it were me or my family in that situation, I’d want the highest trained, most capable team member making decisions on how to build the rescue system.”

In short, Amidon hopes that his research might encourage leaders in the fire service to push for a paradigm shift of teaching firefighters not just how to do the skill, mechanically and physically, but also the intellectual knowledge side of firefighting. This will allow them to independently assess and communicate risks on rescue and fire scenes that will help keep firefighters safe.

“We could do a better job of training and empowering folks of all ranks about how they can communicate and better read a situation,” he said. “We could do a better job empowering firefighters to raise a warning flag when something’s not working, but that will take a shift in firefighting culture.”

The Great Conversations speaker series supports the Ann Gill Faculty Development Fund, a featured fund within the $1 billion State Your Purpose — The Campaign for Colorado.

The Great Conversations speaker series supports the Ann Gill Faculty Development Fund, a featured fund within the $1 billion State Your Purpose — The Campaign for Colorado.