Water. Those of us fortunate enough to have easy access to this essential resource might not think about how much we use or whether those uses are worthwhile. And if we do, we might not know what we can do to be better stewards.

In honor of World Water Day, March 22, SOURCE asked Colorado Water Center Director John Tracy a few questions – maybe even some that have been on your mind. His answers might surprise you. You could even see the glass as half full.

What does World Water Day mean to you?

World Water Day means reflecting on how we are interconnected through water. The water you use either evaporates into the air, which becomes somebody else’s water supply, or it goes down the drain to a water treatment plant and gets treated and sent back to the river, which is somebody else’s water supply. The water we use is somebody else’s supply, which means somebody else’s use is our supply.

How concerned should we be about the Colorado River drying up?

The Colorado River Compact was set up to allocate 17.5 million acre-feet a hundred years ago, and there never was 17.5 million acre-feet to allocate in the first place. It was an imaginary number that came about through a political agreement. Over the years, climate change has led to a decrease in overall water supply in the Colorado River. The last several years were very bad drought years, but if you looked at the total water supply, it was still about 12.5 million acre-feet. The idea of the river drying up completely, that’s just not within the realm of possibility now. In 100 years, who knows? But that’s not where we’re at right now. The question becomes: Who’s going to use less water? The second decisions are made and everybody has certainty with what they really have – both in terms of an agreement and in terms of what I call real water – with that level of certainty, people will be able to make good decisions and move forward.

Does Colorado have a water crisis?

We have continuing issues we have to deal with. It’s not so much a problem of not having enough water or knowing what we have to manage. We’re having to live with politically negotiated documents that don’t reflect either the physical situation or the value system we’re under right now. Climate change is affecting our snowpack, which is affecting our runoff, and it is making some management difficult because the snowpack is coming down a little earlier, there’s more consumptive water use higher up in the watershed, and it’s having real impacts. But there’s a lot of other issues that just have to do with living within the constraints of the compacts. It’s harder, and we’ve got to put more time and effort and money into it, but it’s not a crisis in my mind.

What is Colorado’s biggest water issue?

Workforce. Everybody talks about infrastructure to solve our water problems. But when you build this infrastructure and you have all these management systems and you have to live within the constraints of our river compacts, you need a sophisticated workforce to understand how to operate and manage all of this. I think that’s where our challenge is. There’s not enough of a workforce development pipeline right now, and part of that is, it’s still a very traditionally white, male field. If you’re not recruiting from the entire workforce, which is much more diverse than it was 30 years ago, the pool you’re recruiting from is too small.

Do we have to worry about turning on the tap and not having water?

It depends on where you are and how well your water supply system is maintained. There are areas across the U.S. that have relied on shallow groundwater wells for water supplies that have seen groundwater levels drop enough that their wells can no longer produce water. The simplest solution to this problem is to dig a deeper well, but this can be expensive and in the long run results in “a race to the bottom” with the deepest well winning. This problem does exist for some homeowners in Colorado, but primarily for those who use self-supplied groundwater and live in areas with heavy agricultural groundwater use. For Coloradans living along the Front Range who receive their water supplies from municipal providers, this is not really a problem.

You have said that Colorado is using less water now than it was 20 years ago, despite population growth. How is that possible?

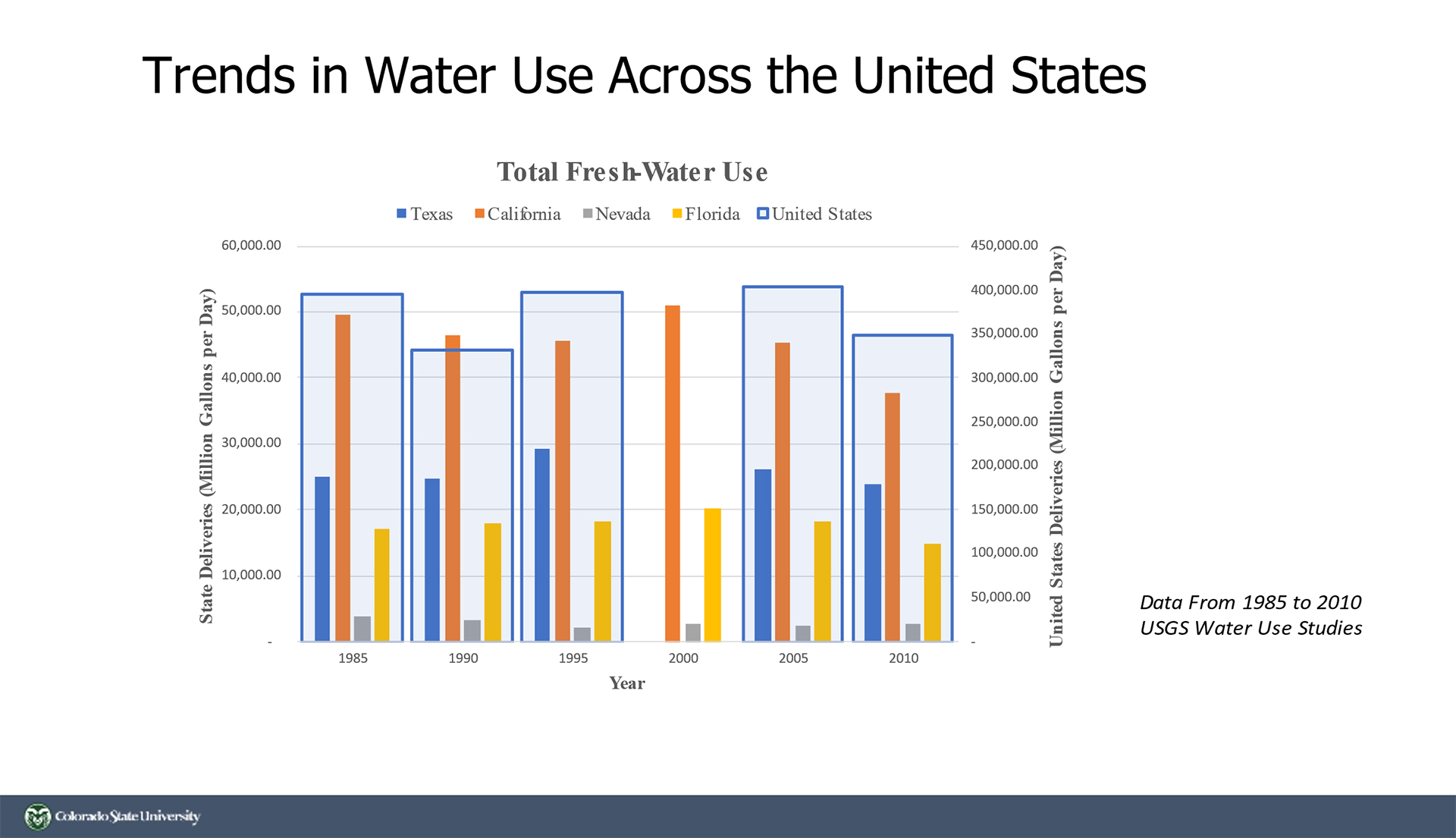

I am working with a class of undergraduate environmental data science students to have them analyze this situation. Here is a graph of overall water use for the U.S. and some of the fastest growing states since 1985. All states are reporting less water use since 2000, and this trend is continuing.

The simple answer is that this decline in water use is directly related to increased efficiency. But it should be stressed that there is a difference between water use reported to the USGS and consumptive water use, which relates to water that is used for economic gain. I have not seen any statistics on changes in consumptive water use, but new tools are being developed that will be much better at assessing this statistic.

What should we think about/do at the individual level to respect our water resources?

We need to be aware of the value (economic, ecological, social, spiritual) we are getting when we use water. Before 2000, we used a lot of water without getting any value for it. The more we pay attention to the value we receive from our water use – whether it is watering a section of lawn for our children to play on, having it flow in the Poudre River so we can float the river, irrigating our crops or simply enjoying a sunset over a lake – the more we will respect water and be better informed in our decisions on how to manage water as a society.