Researchers led by the Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere (CIRA) at Colorado State University have shed light on detailed properties of upper-atmospheric motions, using low-light satellite imagery from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (Suomi NPP) mission. The research has been published online Nov. 16 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

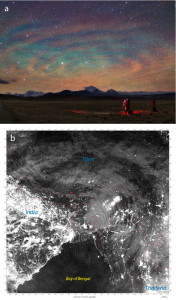

At altitudes between 50 and 60 miles (about 90 kilometers), various photochemical processes create a faint emission of light called “nightglow.”

Initial discovery of light sensitivity

An initial discovery that the Day/Night Band instrument on Suomi NPP held an unexpected sensitivity to this faint light source enabled the first visible detection of clouds on moonless nights.

The researchers have since discovered that the instrument can detect signals from atmospheric gravity waves, which impact the structure of the nightglow layer itself. The imagery details these structures at a resolution of 742 meters, which is unprecedented from space-based observations.

Gravity waves are created by a variety of phenomena in the lower atmosphere, including weather systems, tropical storms, strong thunderstorms, the flow of air over mountain ranges, and even volcanic eruptions (the first documented example of which is included in the article).

Like ripples in a pond

The wave structures, sometimes appearing as ripples reminiscent of a stone dropped into a pond, provide detailed insights on the processes that drive the circulation of the upper atmosphere. The new measurements could be significant for their ability to improve basic understanding of these processes, and potentially to improve long-term climate forecasts.

Led by CIRA Deputy Director and Senior Research Scientist Steve Miller, the research team includes other CIRA scientists as well as partners from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Hampton University, Boston University, the North Western Research Associates, the Jülich Supercomputing Centre in Germany, and the Czech Hydrometeorological Institute. The international team draws together leaders in satellite remote sensing and upper atmospheric dynamics to address a new frontier of interdisciplinary research.

CIRA was established in 1980 as in interdisciplinary partnership between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Colorado State University.