Claim Building Dig

Archaeology students help solve a long-buried CSU history mystery story by Kate Jeracki photos by John Eisele video by Ron Bend published July 22, 2020Everything has an origin story: HP starting in a Palo Alto garage, penicillin discovered by accident. Colorado State University is no different, tracing its 1870 founding to the federal Morrill Act signed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1862.

Like any good origin story, however, there’s more to it, including the first building on campus that had been lost – and now is found.

While the Main Building – known as Old Main when it burned in 1970 – was the first academic structure on campus, housing classrooms, labs, gyms, offices and the president’s residence, it was preceded by a building that never appeared on any campus map.

At first, the Claim Building had one job: to secure Fort Collins as the site of Colorado’s land-grant college once the territory became a state in 1876.

Gov. Edwin McCook and the Territorial Legislature had designated Fort Collins as the site of the state’s agricultural college in 1870, but initially provided no money for its construction. In February 1874, the legislature finally allocated $1,000, but it was a kind of matching grant –“public-spirited citizens of Fort Collins and vicinity” had to come up with an equal amount to receive the funds. They did, but by that time groups from Boulder and Greeley were lobbying lawmakers, arguing that they could open a school sooner.

So, to protect the town’s preferred status, Fort Collins movers and shakers who had received large parcels of land via another 1862 federal law – The Homestead Act, which “opened” land that previously was lived on and used by the Arapahoe, Cheyenne and Ute people to European settlers – stepped up. The businessmen donated a total of 240 acres about a mile southwest of the then-town that became CSU’s original campus. Their names are commemorated on the Pioneer Monument south of Routt Hall and appear on streets throughout Old Town.

The local grange held a picnic on the land that spring and planted 20 acres of wheat. And before the snow came in November, a local banker and member of the as-yet-hypothetical college’s board sketched out and commissioned construction of a small brick building that essentially would stand as a kind of claim for the college in the far northeast corner of the property, near the intersection of Laurel Street and College Avenue.

The building did its job, and Fort Collins was codified as the location of the state’s land-grant college in the Colorado constitution three years later.

Now the rest of the story. Aside from the ethically and morally questionable practice of “claiming” land that had been taken from Indigenous peoples less than a decade earlier, over the years the exact location of the Claim Building was forgotten.

Unearthing origins

Mark Luebker began researching untold stories of CSU for the sesquicentennial celebration when he joined the President’s Office as a content developer and editor in 2018. He quickly discovered that there were several unresolved issues surrounding the Claim Building – sometimes called the Claim Shanty, although it was reported to be a brick structure of 16 x 24 feet.

“It never appeared on any map, we can’t find any building plans for it, there are no existing photographs of it, and the only sketch of it probably was made six years after it had been demolished, when President Alston Ellis asked the governing board for money to preserve the history of the college,” he explained.

Even though the Claim Building stood for only 16 years, it served a variety of purposes. It stored that first crop of wheat harvested from what is now the Oval; the college’s first president, Elijah Edwards, and his family lived there for a few months until they could move into Old Main; it was also a toolshed, a rental dwelling and a chemistry laboratory, and eventually had a substantial greenhouse added to it before it was torn down in July 1890.

Campus lore has it that bricks from the claim building were used in the 1891 construction of the Potting Shed that still stands to the west of Routt Hall.

But Luebker could not pinpoint its exact location without a different kind of digging.

Story update

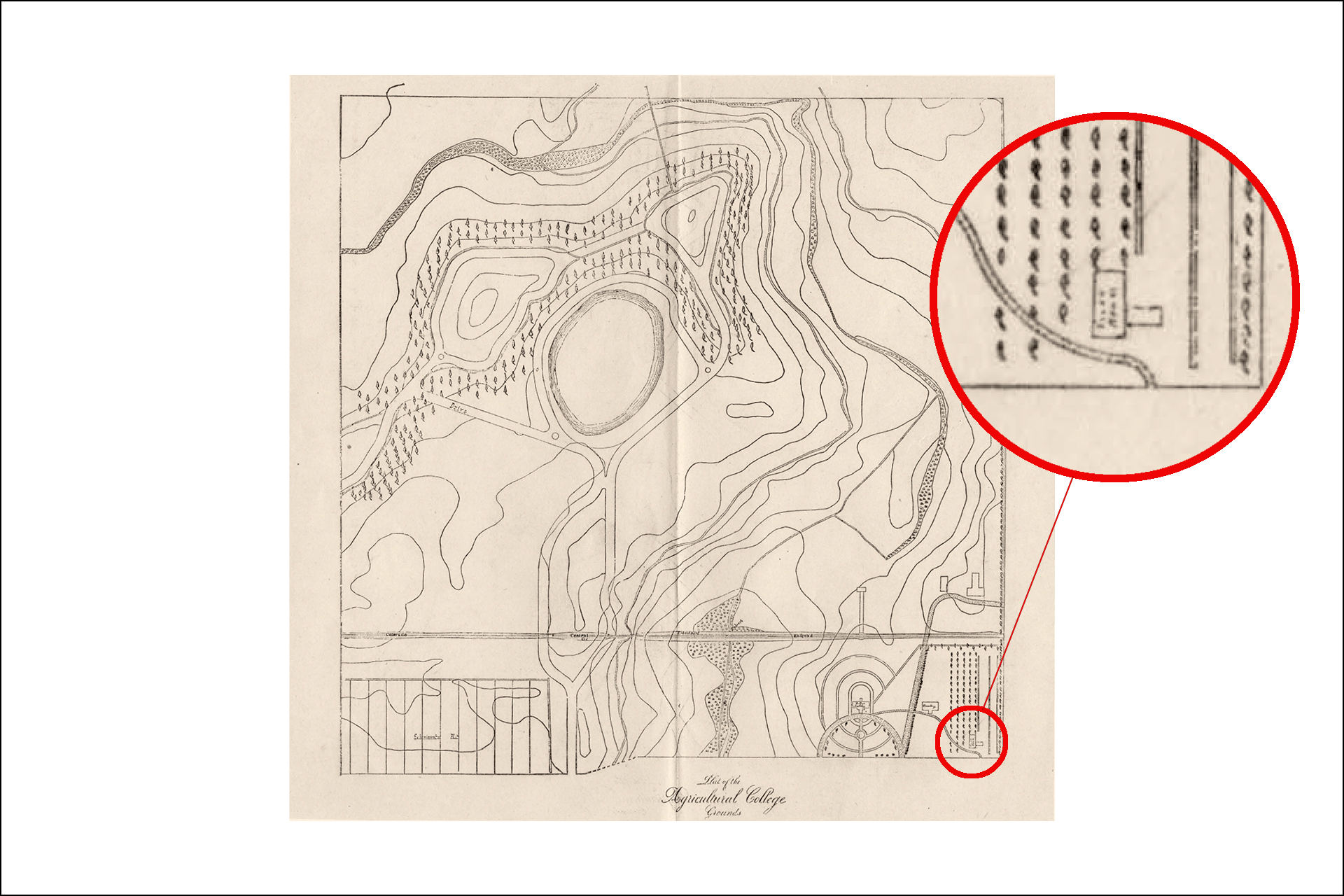

Shortly after this story was published, Gordon “Hap” Hazard — the president of the Fort Collins Historical Society, longtime volunteer in the CSU Archives and Special Collections, and 2004 CSU retiree — sent over the image below from the Fifth Annual Register of the Officers and Students and Courses of Instruction, 1883-84. The Claim Building is located in the lower right of the map.

Mapping underground

Enter Ed Henry, assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology and Geography and director of the Center for Research in Archaeogeophysics and Geoarchaeology (CRAG) in CSU’s College of Liberal Arts. At Luebker’s suggestion, and with funding from the President’s Office as part of CSU’s 150th anniversary observances, Henry adopted the search for the Claim Building as the project for his Fall 2019 class, Digital Digging, that teaches students the foundations of near-surface geophysics in archaeology.

Based on the archival research, the class focused on the open lawns in front of Spruce and Routt halls. They analyzed existing data from LiDAR scans of the campus, and gathered original readings of the area through geophysical methods including magnetometry, electromagnetic induction, and ground-penetrating radar.

Not only did this give students a chance to learn how to use important tools in modern archaeology, once the data were collected, they also used an array of processing software to analyze the findings. The results showed the existence of foundations of two structures almost perfectly matching the reported dimensions of the Claim Building and the attached greenhouse.

Henry and the students presented a report on the project in December. Their most exciting discovery was an unexpected anomaly that could be a privy, a possible trove of artifacts.

Planning an excavation

Archaeology students participate in a dig at the corner of Laurel Street and College Avenue to locate the Claim Building.

Henry and Mary Van Buren, professor of archaeology, had planned an excavation of the site as part of the annual Archaeology Field School, which has been running since 1969. It trains a small group of students each summer in archaeological techniques and practices, including surveying methods, excavation strategies, and cultural resources management.

Over the years, the field school has worked around Colorado and beyond, including ancient Indigenous sites and abandoned settler communities, while providing students eight college credits and valuable field experience.

Enter the COVID-19 pandemic. All teaching and learning at CSU moved online in March, and field schools across the nation were canceled.

Henry and anthropology department chair Mica Glanz decided to ask CSU for a variance to allow the 2020 field school to go on.

“Knowing that a handful of field-school students needed these credits to finish their undergrad careers and get their diplomas in hand this summer was a driving reason to push to make this field school happen during the pandemic,” said Henry. “I really wanted to make sure nobody had to hold off an extra semester or potentially another academic year to finish their degrees.”

Graduate student Carly DeSanto is taking part in the research and serving as a teaching assistant for the field school. She said the importance for students to have this experience can’t be overstated.

“Without experience in a field school, you can’t get a job, and with all the other schools shut down this summer, where will they get this experience?” she said. “They could make up the credits, but not without staying in school for another semester. They are all so grateful for what Ed and the department have done to make the field school happen.”

Taking safety precautions

Participants follow COVID-19 health and safety protocols, which include wearing masks. Under the approved research plan, it was recognized that social distancing would not always be possible due to the scope of the project; when it wasn’t, even in open air, masks are worn.

Following the first week of online instruction on field techniques and project details, the 11 students plus faculty stepped onto the sunny campus lawns in early July, with plans to excavate through the rest of the month.

To allow the work to go on, all program participants wear masks in the field, receive daily temperature scans, take regular water and rest breaks, and follow other COVID-19 health and safety protocols during workdays as well as outside of class. The students have agreed to limit their social interactions during their off hours, and one participant who was not living in Fort Collins arrived a week early to self-quarantine before the dig began.

By eliminating the need for shared housing and extended travel to a study site, “we’re in a unique position,” said Henry. “This does allow us to create one model for doing fieldwork going forward during the pandemic.”

“This does allow us to create one model for doing fieldwork going forward during the pandemic.”

— Ed Henry, assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology and Geography

Perhaps most importantly, it also gives students a much-desired opportunity for field learning and interactions with peers and professors after the academic year was cut short.

“We know students are craving face-to-face learning experiences, and that the move to online teaching is not how any residential student imagines their undergraduate experience to unfold,” added Glantz. “We are so happy to bring back a little bit of normal for our students, and to engage them with all senses – even with masks on and hand sanitizer at the ready. We are anthropologists, we adapt.”

Henry said he worked closely with Fred Haberecht, university planner and assistant director of Facilities Management, and Kurt David, utilities services lead, not only to gain insight into the survey area but to secure the site and make sure the survey flags weren’t mowed over or the excavation irrigated.

Findings so far

Excavators handle a cartridge with powder still in it very carefully.

In the first two weeks of excavation, the team has determined definitively that the site under the lawn at Laurel and College was once occupied by a building with two doors and the dimensions of 16 x 24 – confirming early reports – with a larger structure, presumably the greenhouse, attached to its south side. They have reached a depth of 30 cm below the surface.

One of the first discoveries, a 1868 Seated Liberty dime, was uncovered by student Harry Lane.

“I saw just a little glint of sliver, pulled it out, and washed it off,” he said. “I thought that was pretty awesome.”

— CSU Anthropology and Geography (@CSUAnthGR) July 16, 2020

They’ve also unearthed glass beads from the same era, charcoal in the presumed privy, and most exciting for DeSanto, bricks.

“After the dig, we can analyze the bricks and compare them to the ones in the Potting Shed, and confirm that materials from the Claim Building were used to build it – or not,” she said. “I couldn’t be happier that our work here is adding to the history of Colorado State. Without interpretation – if no one understands what we’re doing – what’s the point?”

“I couldn’t be happier that our work here is adding to the history of Colorado State.”

— Carly DeSanto, CSU graduate student

The field school will be digging at the site into the first week of August, but the last days will be spent returning the carefully saved soil to the excavations and restoring the lawns to a safe state. That doesn’t mean the end of further exploration, however.

Henry would like to return to the site with future classes or field schools and go deeper – both figuratively and literally – to dig into the history of the Indigenous peoples of Northern Colorado who were on the land before the college was even imagined. He said that the Claim Building site is actually among the “newest” that he and Van Buren have studied. Their own research efforts have focused on Indigenous peoples, cultures and sites that can be centuries older.

Henry notes that Michigan State University has a continuing archaeology program dedicated to uncovering and preserving campus history. Luebker, who was at MSU when that program was getting started, supports work continuing on the CSU Claim Building site.

“The side of the Pioneer Monument that faces campus is blank,” Luebker said. “I think that’s a powerful metaphor – inadvertent, to be sure – for the untold stories of all the Indigenous people who were stewards of this land in the years before the college. Their stories also need to be told.”

Public days

The field school will hold “public days” on Fridays in July, when visitors can tour the site by appointment to respect COVID-19 protocols. To schedule a visit, contact Josh Zaffos, communications specialist, Department of Anthropology and Geography: (970) 443-4747 (mobile) or joshua.zaffos@colostate.edu.

To support the work of the department and the Archaeology Field School, go to the website.