Colorado State University psychology major Paige Robertson was in the Larimer County Jail, working on an internship for her social psychology class. She heard footsteps, then saw a deputy and an inmate round a corner and come into view. The inmate wore a khaki jail uniform. She was one of the jail’s transgender inmates. Felicia (not her real name) is biologically male but identifies as female.

Robertson greeted Felicia with a smile and a nod. “Hi, how are you doing?” she said. “Want to chat a bit?”

Felicia, blond, about six-feet-tall, gathered her hair and tied it into a ponytail at the crown of her head. “Sure,” she said, smiling broadly.

They went into a small interview room adjacent to the jail pod. Once seated, Robertson leaned forward, signaling that she was ready to listen.

Felicia talked. About her life, her family history, and the choices she’d made that led her to being incarcerated.

Internship through PSY 315

Paige Robertson’s internship at the Larimer County Jail didn’t begin with her sitting down with inmates like Felicia, encouraging them to be more introspective and to think about the paths they’d taken that brought them there. But one thing led to another.

The tall, ebony-haired 19-year-old with wide-set, intelligent eyes, learned of the internship in her PSY 315, social psychology class being taught by CSU Professor Jennifer Harman. “One day she told our class that she and Dr. Tara Shelley from the Department of Sociology had been asked by the Larimer County Jail to evaluate a program there.

“The program was called Transformations and was designed to help inmates understand their personalities and how the choices they’d made had impacted their lives. They were looking for interns to enter data for the study, so I volunteered.”

‘My first day at the jail’

Robertson vividly remembers touring the jail on the first day of her internship and feeling a bit uneasy.

Lt. Staci Shaffer, the ranking officer over civilian employees in the jail, stood beside Robertson inside the sally port at the west end of the jail. Shaffer was a petite, self-possessed woman with a quiet, discerning gaze. She turned that gaze on Robertson and said, “All our inmates begin their stay with us at the jail in this way. They come through here, then booking. I want you to see this facility through the eyes of someone who’s coming here for confinement.”

Robertson took in her surroundings. The sally port was a large garage with two overhead doors. They were like eyes that blinked independently of one another. When one went up, the other went down — a security feature that closed escape routes.

“This is where the deputies park their cars and remove their prisoners,” she heard Lt. Shaffer say.

Robertson looked down at a wide parking stall. The walls and floor adjacent to it were covered with thick pads. They reminded her of safety mats used in wrestling and gymnastics.

“Occasionally when prisoners are driven in here, they become combative and need to be restrained,” Shaffer explained. “The padding is there for the prisoner’s and the deputy’s safety.”

They walked through the sally port and into booking. As the steel door closed behind them, the world changed. It became a world of brittle sounds — the ratcheting of mechanisms that slid the heavy doors shut, the resounding bang as each door met its door frame. The walls were cinderblock, the floors gleaming. Somewhat surprising — the inside of the jail had a clean, fresh smell.

The two women moved through a room where strip searches are conducted and paused before a heavy door, waiting for a deputy monitoring them by video to unlock it remotely.

Lt. Shaffer and Robertson went from one inmate pod to another. The pods for general female and male populations. The pod for inmates with mental illnesses. One for prisoners who exhibit violent or self-destructive behavior. A cell block for sex offenders. One for transgender inmates.

“It was kind of overwhelming,” Robertson admitted. “I thought, ‘I don’t know if I want to come back here. Spend my time here. Everyone is staring at me, and I’m staring back at them.’ It’s just weird — the fact that you can walk out the door and go home while a lot of other people can’t.”

The day that Robertson walked through the sally port and into the jail would end up expanding her world in ways she couldn’t begin to envision.

But she did come back. Bolstered by the confidence her CSU professors had instilled in her. Inspired by Lt. Shaffer and the example she set.

“Lt. Shaffer’s female presence in the jail reassured me that I could not only adapt but feel comfortable working there,” Robertson said. “It wasn’t just the authority she conveyed, but the respect she’d earned, even among inmates.”

The day that Robertson walked through the sally port and into the jail would end up expanding her world in ways she couldn’t begin to envision.

But on the day of the jail tour, she admits she really didn’t have a plan. All she knew was that she was willing to entertain the new and take advantage of opportunities.

Before coming to CSU, she’d attended Conifer High School in a mountain community nestled in the foothills west of Denver. She was a school athlete and worked for a realty company as their front desk receptionist.

Like many Colorado residents, when it came time to choose a college, her university-of-choice was CSU. “It was in-state and a great value,” Robinson said. “I had several friends from high school who were older and had gone to Colorado State. I also liked the honors program that CSU offered.”

The CSU Center for the Study of Crime and Justice was in charge of the study of the Transformations Program, supported by the data entry Robertson and other interns were doing.

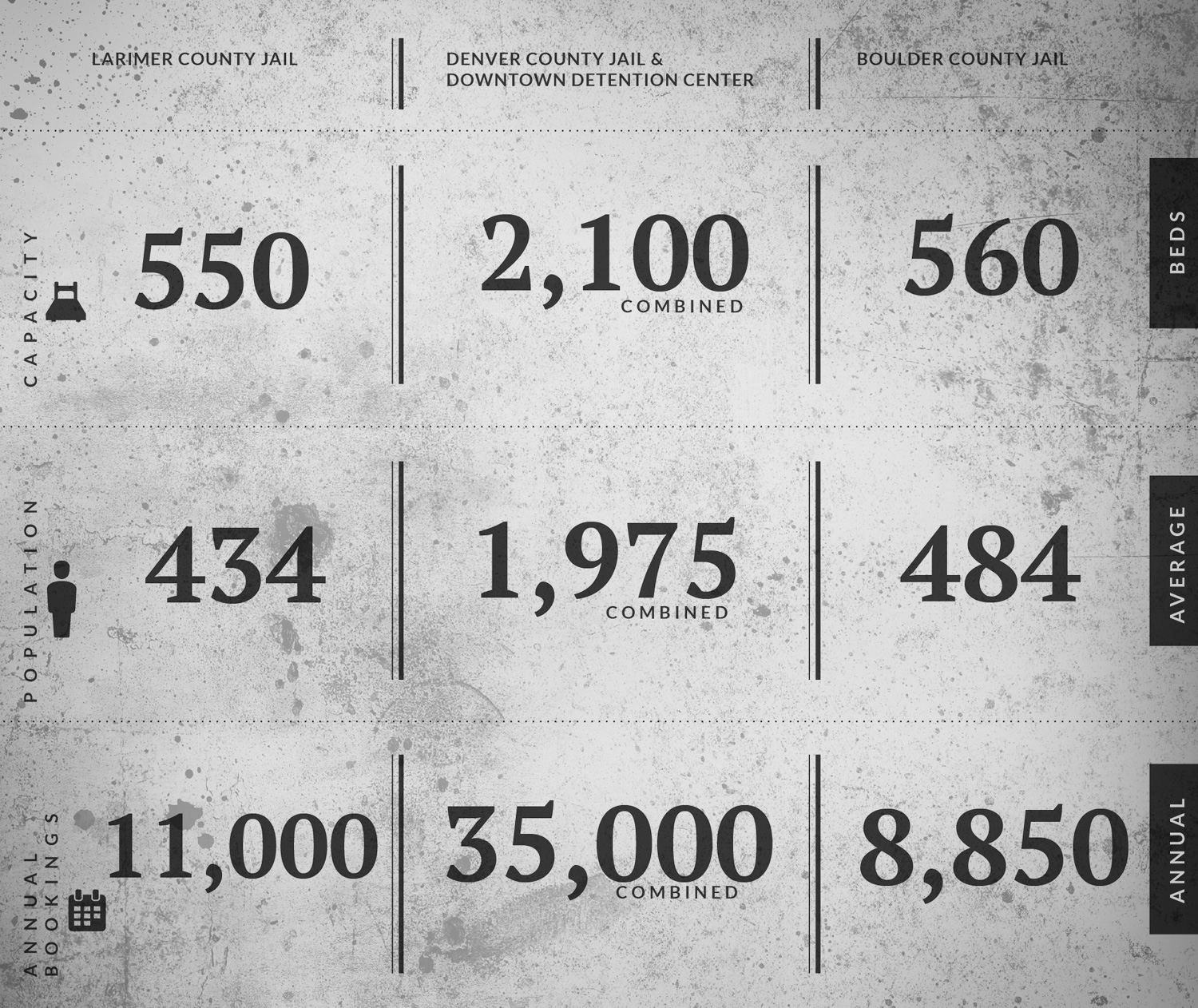

The jail had done an initial study of its own and found that, of those who completed the Transformations class, only 30 percent came back to the Larimer County Jail. Nationally, the number of inmates who reoffend and return to jail is 70 percent.

“Paige dived into the data entry required by her internship, but she was always volunteering to do more,” Lt. Shaffer said. “She showed an interest in and curiosity about everything going on here.”

“My senior honors thesis grew out of my interviews with inmates,” Robertson said. “I was asking questions like, ‘How is your family impacting you while you’re in jail? I created a children’s corner in our new video visitation area and a communications guide to help inmates and their families make their relationships stronger, since that has such a great impact on whether or not they came back to jail.”

“I was really impressed with her wanting to do that,” said Professor Harman, who supervised Robertson’s project.

“Paige created a pamphlet that addressed, ‘How do you explain to a child that his or her dad is in jail? Especially when the child is young? When you have limited contact and only a few minutes to talk, how can you make the most of it?’

“I was impressed with Paige as a whole. I always encourage my students to approach their education with the idea that they are crafting their careers — their life’s work. Paige did that.”

Inmate behavior

Robertson and the other interns were not only looking at recidivism rates (the rate at which inmates reoffend and are reincarcerated) but at criminal histories and inmate behavior in the jail.

After Transformations, were the inmates becoming more pro-social, less aggressive? Were they making their beds, becoming less verbally abusive toward staff? Were they feeling more invested in their relationships with family and friends? If they came back to jail, was it for a less severe crime?

Although the recidivism piece of the data from the Transformations study is still being cleaned and sorted by CSU, profound evidence of its impact is being seen among both male and female inmates.

Transformed: An inmate named Julie

Julie identified herself as a recovering heroin addict and said she was serving a one-year sentence for possession of stolen property.

One inmate said the 40-hour Transformations class made her feel as though – for the first time in her life – she was seeing herself through a new lens.

For her interview, Julie (not her real name) came into a small room off her jail pod. Her face was open, her gaze soft. As she talked, she made sweeping gestures with her hands or used them to smooth her hair away from her face.

Julie is a Caucasian female, 28, single, without children. She identified herself as a recovering heroin addict and said she is serving a one-year sentence for possession of stolen property.

“I was so lost, distraught and broken when I came here,” she said with a small quiver in her voice. “My worldview was very one-sided. It was black and white. There was nothing in between. Very pessimistic. No trust. After I signed up for the Transformations class, I took the Myers Briggs personality test and got my complete profile workup — and that blew my mind. It was so on point. I got a glimpse of the gray area, and the world rotated into a different view for me.

“I learned that I am very emotionally driven and that my thinking patterns have dictated a lot of my choices. I had a negative concept of myself and a core belief since I was very young that I didn’t know was affecting me the way it was. By the third day …it was emotionally exhausting. It was brutal. To be so open, vulnerable, and to express the hurt and pain.

“But for the first time in six months — I can’t explain it — I felt like I wasn’t in jail. Vicky Connell, the program facilitator for the class, was right by my side, along with the other women in the class.

“Now, I am strong enough to walk away from doing something criminal. I know the value of myself. My relationship with my mother has grown so strong. It’s got to be a very different outcome for the rest of my life.”

“The biggest thing inmates learn out of the Transformations program,” Robertson said, “is that it’s not their background that’s making them do this stuff. It’s them.”

Robertson has been working with “Felicia” for over a year.

Felicia is Caucasian, 34. She was raised in the South and in conformity with her biological gender until her early teens. “Substance abuse is her main issue,” Robertson said. “She gets caught up in other crimes when high on drugs. She’s been in and out of our jail for years.

“As a result of attending religious programming in the jail, she wants to seriously change her lifestyle and be there for her kids,” Robertson said. “She starts the Transformations Program on November 10.”

“The biggest thing inmates learn out of the Transformations program,” Robertson said, “is that it’s not their background that’s making them do this stuff. It’s them.

“If they get angry or are otherwise lost in their emotions and are on the verge of repeating a pattern, they know they can do something different than resorting to substance abuse, which often leads to committing crimes. It’s never too late for them to better themselves.”

‘I want to help these individuals’

“I love this work. I like working behind the scenes to serve and protect my community. I want to be able to help these individuals the best I can. Listening to them, listening to what they think, could help them. That’s what’s driven me to continue in this path.

“I’m happy I made the choice to come to CSU,” Robinson said. “The professors and instructors were incredibly welcoming. I can’t remember any of them hesitating to offer extra help or opportunities to enhance my education.

“In particular, Dr. Harman and Brad Hurst, an instructor in the Department of Sociology, made the biggest impacts on me as far as the career path I’ve taken.”