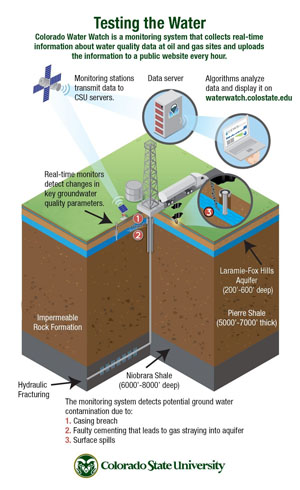

A steady stream of data collected at oil and natural gas sites in the Denver-Julesburg Basin flows into a server at CSU, where researchers use it to analyze groundwater quality.

Complex algorithms sift through the raw data, scanning for any anomalies or sudden shifts in water composition that could indicate contamination in a groundwater well. The data is analyzed and displayed as charts and graphs on a CSU website for the public to view, updated with new field data posted every hour.

The network of monitoring stations and website are part of the Colorado Water Watch, a project spearheaded by CSU researchers to provide the public with real-time information about water quality at oil and gas sites throughout the basin that underlies northeastern Colorado and the Nebraska Panhandle.

The CSU team is led by Ken Carlson, a professor of civil and environmental engineering, who believes it is the first monitoring system of its kind in the country.

“We don’t know of anyone else in the country who is collecting real-time data from groundwater wells next to oil and gas operations, evaluating potential changes with advanced anomaly detection algorithms and sharing it with the public,” Carlson said.

Water and energy

Carlson specializes in water quality research and over the years has narrowed his focus to the impacts of energy development on water. He leads the Center for Energy Water Sustainability, part of the Energy Institute at CSU.

In recent years, most of his work has centered on water and hydraulic fracturing.

Hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” is the practice of drilling deep wells – 6,000 to 8,000 feet in the Denver-Julesburg Basin – into a layer of rock that contains oil and methane gas. A mixture of chemicals and water is injected to break up the rock and release the oil and gas that is then extracted.

Hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” is the practice of drilling deep wells – 6,000 to 8,000 feet in the Denver-Julesburg Basin – into a layer of rock that contains oil and methane gas. A mixture of chemicals and water is injected to break up the rock and release the oil and gas that is then extracted.

Critics believe fracking is unsafe and, among other things, pollutes critical groundwater supplies.

Proponents defend the practice, saying there is no evidence hydraulic fracturing is releasing pollutants into groundwater supplies.

The topic has become increasingly controversial in Colorado and the nation.

“It’s gotten to the point people cannot have a civil conversation about it,” said Carlson. “Everyone produces studies that back up their beliefs. This could lead to confusion and some people may feel they do not have enough information to make informed decisions.”

Enter Colorado Water Watch, a real-time monitoring system to provide the public with easy-to-understand water quality information.

Gathering support

Carlson approached former Colorado Gov. Bill Ritter, who directs CSU’s Center for the New Energy Economy, about creating Colorado Water Watch during the 2012 Natural Gas Symposium.

Ritter liked the idea and from there, the two met with representatives from Noble Energy and the Colorado Department of Natural Resources, which oversees oil and gas issues in the state.

Both Noble and the state agency agreed to support the project and serve on the steering committee along with representatives from Western Resources Advocates, a conservation group; the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission; and the Colorado Oil and Gas Association industry group.

“One thing that makes this project unique is that we involved a variety of stakeholders in the project,” Ritter said. “We have approached this with a spirit of collaboration, and that has been highly beneficial to the project.”

Based on science

Carlson and his research team have spent the bulk of the past 18 months developing the monitoring system using off-the-shelf sensors, identifying Noble-owned or -leased sites to install their equipment, and designing algorithms to crunch data coming in from the field.

The team has published several papers related to their work in peer-reviewed journals including Environmental Science and Technology and Journal of Applied Water Science.

“We wanted this to be based on sound, proven science,” Carlson said. “We’ve spent a lot of time working on that and validating the system and our results.”

Sensors and stations

So far, the CSU team, which includes Asma Hanif, research associate, and Jihee Son, a post-doctoral student, has installed four monitoring stations as part of the proof-of-concept phase of the project.

Three are located next to active oil and gas wells throughout the Denver-Julesburg Basin. The fourth is a control site at CSU’s Agricultural Research Development and Education Center – or ARDEC – near Wellington.

Each site has a sensor running down a well that collects water data and is connected via cable to a nearby data logger.

The sensors are placed at varying depths to collect information on various water sources. Some snake 40 feet down and monitor primarily groundwater that is vulnerable to spills or other surface activity. Others, such as the Galeton station, are placed 400 feet below ground to collect data on the Laramie-Fox Hills Aquifer, a confined aquifer that could be susceptible to leaks in oil and gas well casing.

Water flows around the sensors, which send information to the data logger every five seconds. That information is then relayed to CSU’s server via a wireless connection.

The system is designed to not only monitor water quality but also act as an early detection system. If it detects an anomaly or major change, Carlson and his team are immediately alerted.

They visit the site, take a water sample and send it to an Environmental Protection Agency-certified lab to be analyzed. With that information, they can identify the source of the contamination – even if it isn’t from oil and gas development.

“The system can detect changes in quality that could be due to any activity in the watershed including oil and gas operations, agriculture, other industrial activity and even urban runoff, Carlson said.

Providing more information

Until now, most of the publicly available water quality data has come from samples taken periodically by operators or regulators.

In Colorado, for example, water samples are collected at a proposed site before a well is drilled, a month after it is in operation, and then five years later. That information is available to the public upon request but is highly technical and can be hard for people to understand.

Information provided by the Colorado Water Watch project will help fill that gap, said Mike King, executive director of the Department of Natural Resources.

“There’s a tremendous amount of suspicion about government and about oil and gas development, and we thought that bringing CSU on and participating would provide that level of objectivity that many in the public felt was lacking,” King said.

Jon Golden-Dubois, executive director of Western Resources Advocates, supports Colorado Water Watch for similar reasons.

“Our interest is ensuring that more information is available and that a larger set of data is developed so that we can better understand the impacts of oil and gas development and fracking on water quality in Colorado,” he said.

The $1.2 million project has been extended beyond the proof-of-concept phase and additional monitoring wells will be installed this fall.

Carlson also would like to add an air quality component.

“If stakeholders – primarily the public and industry – find Colorado Water Watch valuable, the system could be extended for much of the oil and gas areas in the state and maybe beyond,” he said.

Media Assets

Video

- Tracked reporter package, no graphics

- Package nat sound only, no graphics

- Package script with suggested intro and graphics information

High-Resolution Photos

Professor Ken Carlson talks with Asma Hanif, a research associate, and Jihee Son, a post-doctoral student, both of whom are members of the Colorado Water Watch research team.

Professor Ken Carlson talks with Asma Hanif, a research associate, and Jihee Son, a post-doctoral student, both of whom are members of the Colorado Water Watch research team.

Carlson and Hanif check equipment at the team’s Galeton monitoring site in the Denver-Julesburg Basin.

Carlson and Hanif check equipment at the team’s Galeton monitoring site in the Denver-Julesburg Basin.

Sensors are placed at various depths – from 40 to 400 feet – to monitor for surface spills, contaminants in the aquifer and other groundwater sources.

Sensors are placed at various depths – from 40 to 400 feet – to monitor for surface spills, contaminants in the aquifer and other groundwater sources.

Carlson and his research team have spent the past 18 months developing the monitoring system using off-the-shelf sensors, identifying sites to install their equipment and designing algorithms to crunch data coming in from the field.

Carlson and his research team have spent the past 18 months developing the monitoring system using off-the-shelf sensors, identifying sites to install their equipment and designing algorithms to crunch data coming in from the field.