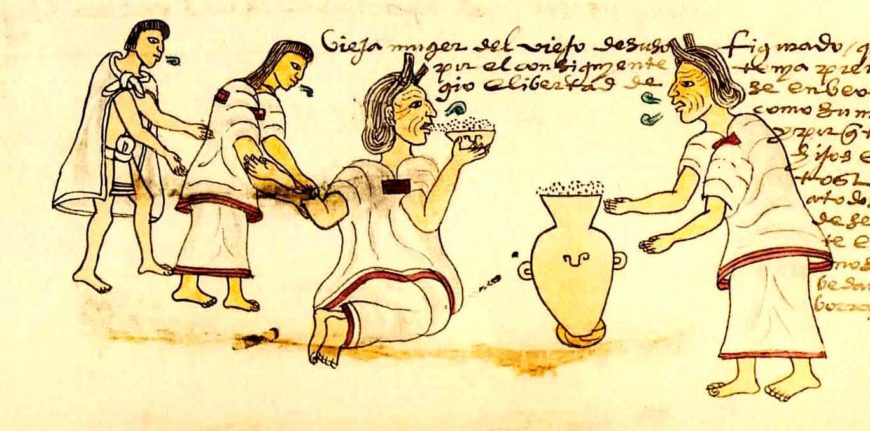

A general scene of a pulque festival from the Codex Magliabechiano.

As the alcohol-infused celebration of St. Patrick’s Day approaches, a Colorado State University faculty member is researching another ancient festival that, while distant from Ireland, was also known for high levels of inebriated revelry.

Catherine DiCesare, an associate professor in CSU’s Department of Art and Art History, got interested in the Aztecs of central Mexico after studying Italian Renaissance art. While taking classes on pre-Columbian art in graduate school she became fascinated by the fact that, at around the same time as the Renaissance artists were working, a half a world away the Aztecs were creating art of their own. And as missionaries from Spain were looking for ways to convert the Aztecs to Christianity, they documented their culture in many accounts that still survive today.

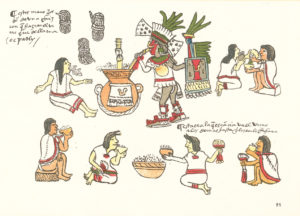

Now DiCesare is working on her second book about Aztec celebrations, this time focusing on the festivals depicted in the Codex Borbonicus, a famous Mexican manuscript about Aztec calendars. She’s especially interested in a particular page of the Codex — one that depicts images of a festival called Quecholli, one of the months of their 365-day solar calendar, as it was carried out in year 1507.

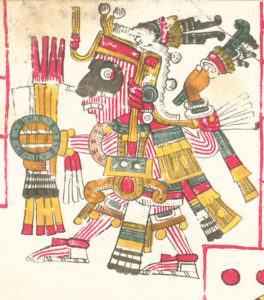

Most colonial sources describe Quecholli as a celebration of hunting and the god Mixcoatl, “Cloud Serpent,” but this page also features Aztec images of drinking excessive amounts of the alcoholic drink pulque, which was made with the fermented juice of the agave plant. Among the images is an enormous vat of pulque, dancers with food offerings, a drummer and a woman serving pulque.

A rare convergence

DiCesare theorizes that this scene was not from just any old Quecholli feast — she posits that it was a massive celebration that only occurred every 52 years, when Quecholli coincided with a day named “2 Rabbit,” a drunkfest on their other calendar, which had only 260 days a year. She argues in her new book that the two calendars were integrated and coordinated by the Aztecs when it came to such festivals.

DiCesare, who delivered a lecture with the colorful title “Pulque and 2 Rabbit Revelry in the Codex Borbonicus Quecholli Feast” at the Denver Art Museum last month, says the Aztecs actually had very strict rules about the consumption of pulque. They issued stern edicts about the circumstances in which one could partake in the beverage, and some documents suggest they might have even sentenced people to be stoned to death for defying the laws. (Once you reached a certain advanced age, however, you could drink as much as you wanted.)

“Among the Aztecs, excessive consumption of alcohol was a marker of uncivilized status,” she explains. “Colonial Mexican manuscripts are filled with cautionary tales of ethnic groups whose unchecked drinking could lead to dire, life-threatening situations and even cultural collapse.”

One Franciscan missionary who lived in Mexico for 50 years and knew the indigenous language wrote that 2 Rabbit was not just marked by roll-in-your-own-feces drunkenness. If one happened to be born on that day, DiCesare says, it was your fate to be a drunk, and as a result you might die by falling off of a cliff. It was believed that drinking too much would cause your life to become out of balance, and you might commit adultery, talk too much or get paranoid.

‘Wallowing in ordure’

The following is an account by CSU Associate Professor Cate DiCesare of the Department of Art and Art History about how drunkenness was described by Fray Bernardino de Sahagun in The General History of the Things of New Spain (Florentine Codex), written in the 1570s:

“The one born on 2 Rabbit was destined to become a great drunkard ‘who required, lusted for, and used wine like a pig,’ gorging himself on wine. Drinking was his one dedication, and he depended on it and consumed it to excess, sometimes skipping meals and even sleep. The drunkard would drink anything, even the dregs, even if it were ‘like spoiled clots, with dirt, or full of gnats — full of filth and rubbish.’ [4:11]

“The besotted ‘went wallowing in ordure, … debauched, with hair tangled, uncombed, twisted, and matted.’ [4:11] It was a sad life. ‘Nevermore thereafter did he live in bliss and contentment.’ [4:11] His hands shook, his words were vile, imprudent and intemperate, and he was destined to be reviled [4:11-13].

“His drunkenness induced him to adultery, to the point of ‘scaling walls to tempt and seduce’ women.

“More, in a chapter on just ‘how many kinds of drunkards there were,’ [4:15] some were not overly affected by the temptation to drink too much, perhaps sitting coiled up in a ball, hugging himself, or even just falling asleep off somewhere alone. Others might become suspicious, even paranoid, misunderstanding the things he heard. Still others simply ‘chattered, jabbered, gibbered, and mumbled.’

“The drunkard born on the day 2 Rabbit was destined for destruction; being drunk left one vulnerable to robbery and murder; or they were liable to meet their death by ‘collapsing somewhere’ or falling from ‘some cliff; or down into a chasm.’ [4:13] He tumbles down a mountain and streams of blood run from his head.”

Strict parameters

“In Aztec ritual life, celebrants were permitted to drink alcohol during certain feasting events governed by the calendars, but even then quantities were limited and taken under clearly prescribed conditions,” DiCesare says. “You could only have four bowls of pulque; if you had a fifth it was excessive.”

Except on the day known as 2 Rabbit, which was notoriously associated with debauchery and overindulgence in pulque. And especially when — once in a lifetime — that day coincided with Quecholli, Dicesare theorizes. Apparently when that happened, all bets were off when it came to getting completely inebriated.

“Most colonial sources represent the Quecholli feast as a celebration of the hunt and the veneration of the god Mixcoatl,” DiCesare says. “Although that god is depicted here as well, the sources do not clearly explain the circumstances for the pulque feast that dominates this page.”

DiCesare’s publications include the book Sweeping the Way: Divine Transformation in the Aztec Festival of Ochpaniztli. She teaches courses on the arts of the Pre-Columbian and early colonial Americas as well as medieval, Italian Renaissance and Baroque European art.

The Department of Art and Art History is part of CSU’s College of Liberal Arts.