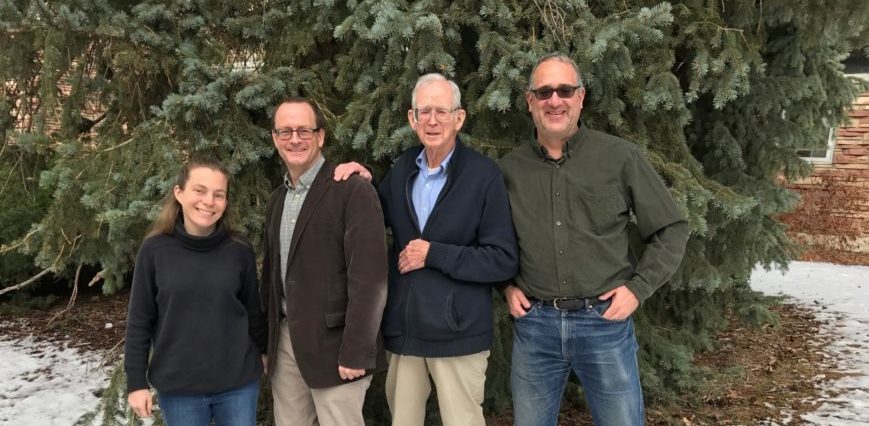

From left are Katie McShane, Kenneth Shockley, Holmes Rolston and Philip Cafaro.

Colorado State University has long been recognized for its expertise in environmental ethics, a field that CSU Professor Emeritus Holmes Rolston helped found in the 1970s.

Now it’s the only institution in the world that has four authors represented in a new environmental ethics handbook from Oxford University Press.

Rolston and three of his colleagues in CSU’s Department of Philosophy wrote chapters in the Oxford Handbook of Environmental Ethics published last November. The others were Professor Philip Cafaro, Associate Professor Katie McShane and Associate Professor Kenneth Shockley, who was named to the Holmes Rolston Endowed Chair in Environmental Ethics last spring.

‘Lasting impact’

“Colorado State is, without doubt, one of the world’s best institutions for research and teaching in environmental ethics,” says Clare Palmer, a philosophy professor at Texas A&M and former president of the International Society for Environmental Ethics. “Holmes Rolston is a founding figure in the subject, and in the early 1990s, I spent the most intellectually stimulating weeks of my career as an Oxford Ph.D. student visiting his environmental ethics class. Those weeks made a lasting impact on me and shaped my subsequent career.”

“Phil, Katie and Ken are all leading scholars in the field,” she adds. “Together they have expertise across wide areas of environmental concern, including ethical debates about population, wilderness, climate change and ecosystem health.”

The four scholars sat down together recently to discuss the discipline, their work and why environmental ethics may be more important than ever.

How we view nature

The field focuses on the ethical issues humans face related to the environment, such as the idea that nature has value beyond simply serving as a resource for humans.

“Ethics explores how we should live, as individuals and within societies,” Cafaro says, citing Rolston’s 1975 journal article “Is there an ecological ethic?” as a seminal work in the discipline. “We ask that question in the context of the environment. It can be about wolves, or water, or general issues like how we justify our ethical decisions.”

“In the early days, it was thought to be weird by some people,” Rolston adds with a laugh. “But it’s about asking whether we have appropriate concern for the values carried by nature.”

“In the 1940s, Aldo Leopold suggested we view ourselves as citizens of the environment, not conquerors,” Shockley says. “We too often focus on how features of the environment might satisfy our immediate wants and needs, rather than on the kind of world we would want to leave our kids. Environmental ethics helps us think differently about our relationship to the environment.”

“Often we value the environment in economic terms,” McShane notes, “but we wouldn’t do that with our kids.”

A good fit for CSU

Shockley says environmental ethics involves one of CSU’s strengths as a land-grant university: putting theory into practice. He said one reason he came to CSU from the University of Buffalo-SUNY is the university’s commitment to sustainability, as evidenced by the first-ever STARS Platinum rating awarded to CSU in 2015.

“Building sustainability into the bedrock of the institution is appealing to me,” he says. “It’s also the chance to work with these three people, who are icons in the field.”

Shockley added that he chose CSU in part because of the multidisciplinary efforts in the School of Global Environmental Sustainability. “The interconnections are fabulous,” he says. “I was blown away.”

Environmental ethics has applications in many other disciplines. For instance, McShane is working with the Department of Design and Merchandising on sustainability in the fashion industry, from energy use to recycling.

“You can go into almost any field and talk about sustainability,” McShane says.

In another example of real-world applications, Rolston said he once wrote a paper that the superintendent of Yellowstone National Park required all of his employees to read.

‘Wicked’ problems

The problems environmental ethics addresses are often thought of as “wicked” problems because, even as the field makes overall progress, solutions provided to specific problems typically lead to further, different problems.

“We need to teach our students how to deal with this wickedness, deal with problems instead of denying them or seeing a simple solution,” McShane says. “It’s emotionally difficult to deal with, but we need more of that in society.”

Sometimes the discipline gets political, as evidenced by the role that the subject of climate change played in the presidential election last fall.

“We provide a space for students to disagree with each other, a space for contentious issues,” Cafaro adds.

“You can’t avoid, and shouldn’t avoid, seeing that these problems are not just individual, but social, and therefore political,” Rolston says, joking that he used to be called the “tree hugger” of the department. “But at CSU I’ve never been pressured to not take a stance.”

Asked when he became fascinated with environmental ethics, Rolston pauses before responding.

“I first got interested in my cradle, in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia,” he says. “I had a mountain on one side and a river on the other.”

The Department of Philosophy is in CSU’s College of Liberal Arts.