Video by Ron Bend/Colorado State University

Next time you go for a walk in the woods, pay attention to the sounds you hear: the flow of a river, wind through the trees, singing birds, bugling elk. These acoustic resources are just as magnificent as visual ones, and deserve our protection.

Rachel Buxton, postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology at Colorado State University, recently offered the advice above when discussing her latest research. She would like more people to think about noise pollution when they’re visiting a national park or protected area.

Buxton is the lead author of a first-of-its-kind study from scientists at CSU and the U.S. National Park Service that will be published May 5 in Science. In the study, researchers found that noise pollution was twice as high as background sound levels in a majority of U.S. protected areas, and caused a tenfold or greater increase in noise pollution in 21 percent of protected areas.

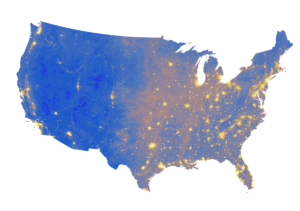

Measuring noise pollution is a challenging task, given its diffusive nature and since sound is not easily monitored remotely over large spatial scales; it can’t be measured by satellite or other visual observations. The team analyzed millions of hours of sound measurements from 492 sites around the continental U.S. and provided predictions of existing sound levels, estimates of natural sound levels, and the amount that anthropogenic noise raises sound above natural levels, which is considered noise pollution.

Noise pollution affects people, nature

Anthropogenic, or human-caused, noise is an unwanted sound created by humans, such as sounds emanating from aircraft, highways, industrial activities or residential sources. Noise pollution interferes with normal activities, such as sleeping and conversation. It can diminish a person’s quality of life.

Noise pollution can also influence nature, changing the efficacy of communication between creatures, such as the spring chorus of birds used to establish territories and find mates. It can alter species’ behavior and use of habitats.

Buxton said the noise levels found in the study can be harmful to visitor experiences, human health and wildlife.

“However, we were also encouraged to see that many large wilderness areas have sound levels that are close to natural levels,” she said. There are many opportunities for people to experience the natural soundscape across the U.S., but these relatively unimpacted systems need to be recognized and protected, Buxton added.

George Wittemyer, a CSU associate professor and senior author of the study, said that numerous noise mitigation strategies have been successfully implemented. Some protected areas have launched shuttle services to cut back on traffic, implemented quiet zones where visitors are encouraged to quietly enjoy protected area surroundings, and created noise corridors, aligning flight patterns over roads.

“We already have the knowledge needed to address noise issues,” he said. “Our work provides information to facilitate such efforts in protected areas where natural sounds are integral, as well as highlighting areas where near-natural levels can still be experienced.”

The interdisciplinary CSU research team includes scientists from the Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology (Rachel Buxton, George Wittemyer and Kevin Crooks), the Department of Biology (Lisa Angeloni), and the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering (Daniel Mennitt).

The Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology is in the Warner College of Natural Resources.