Legacy for $3 million: Professor earns funding for musculoskeletal trauma and cancer research

by Kristen Browning-Blas | August 17, 2015 12:13 PM

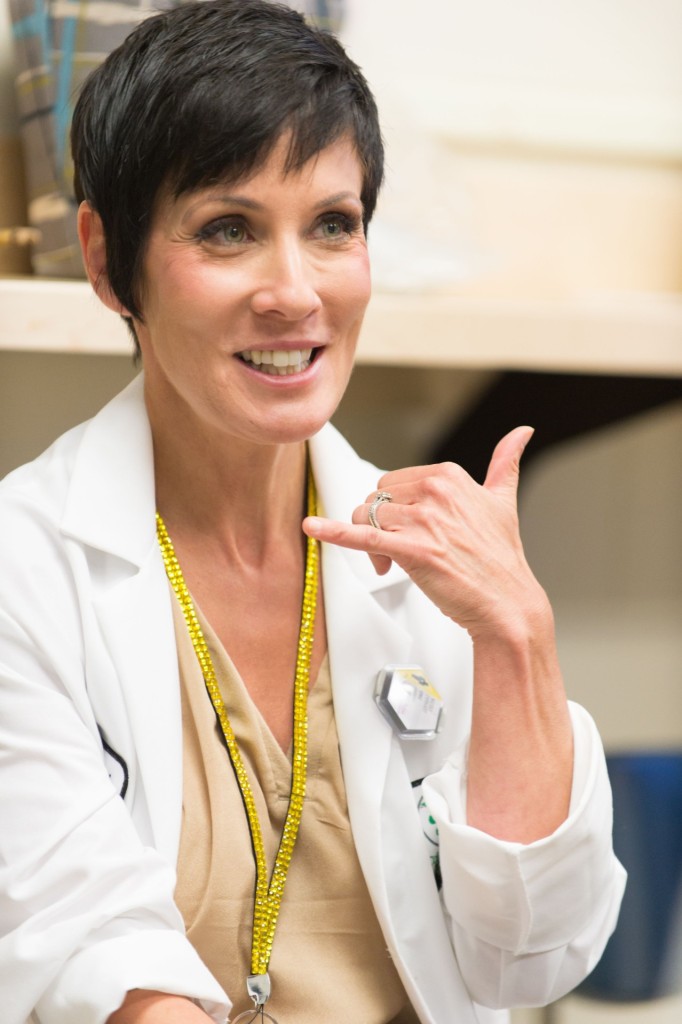

Chairs occupy an important place in academia. They are both physical and symbolic. When Dr. Nicole Ehrhart[1] assumes the Wilkins University Chair today, she will receive an actual chair, engraved with her name and the name of the endowment that will fund her cancer research.

Known officially as the Ross M. Wilkins, M.D. Limb Preservation University Chair in Musculoskeletal Biology and Oncology, the maple chair, trimmed in black and gold, is important for what it represents: a $3 million endowment ensuring the research continues in perpetuity, and the fact that Ehrhart is the first woman at Colorado State University appointed to an endowed University Chair.

“It’s the removal of another glass ceiling,” said Ehrhart, a veterinarian, board-certified surgical oncologist and CSU professor of surgical oncology. “I’m very honored. It’s an opportunity to represent the future on so many levels.”

[2]

[2]At Colorado State’s Flint Animal Cancer Center, she teaches and treats animal patients. She also studies ways to prevent limb loss and to regenerate bones and muscle in people and animals whose extremities are threatened by cancer, infection or trauma. Ehrhart employs surgical and bone-grafting techniques, as well as biologics and stem-cell therapies.

Among Colorado State’s highest honors, University Chairs are funding mechanisms used to support outstanding scholars in their quests for new knowledge in critical fields. Ehrhart is one of 14 CSU faculty members holding academic chairs endowed at $3 million.

“This is a tremendous tribute to Dr. Ehrhart’s outstanding leadership as a scientist and scholar,” CSU President Tony Frank said. “That she is the first woman to occupy an endowed University Chair is a significant — if long overdue — milestone for our institution. CSU has been home to exceptional, accomplished women faculty since its founding in 1870, and Dr. Ehrhart carries on that tradition with her groundbreaking work in human and animal health. We are grateful for this chance to celebrate and support her work at the highest levels.”

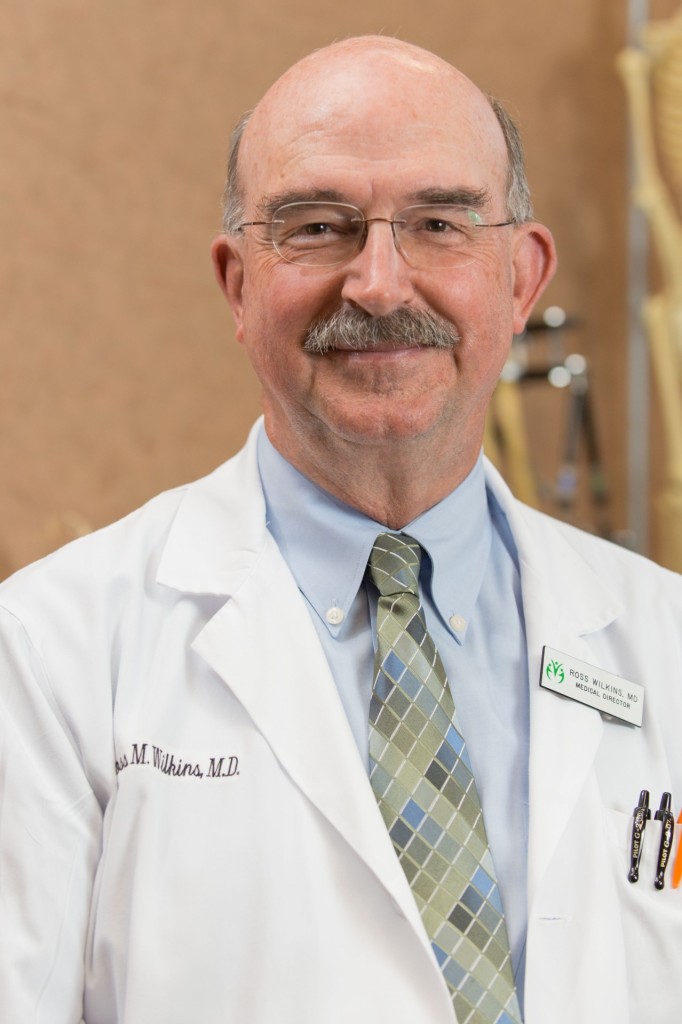

Ehrhart’s appointment to the University Chair is symbolic for another reason: The chair is named for Dr. Ross Wilkins, a Denver cancer doctor who has collaborated closely with Dr. Stephen Withrow, a veterinarian, University Distinguished Professor and founder of the Flint Animal Cancer Center[3]. The two surgical oncologists together developed limb-sparing techniques that have become a standard of care for pets and people, especially children, with bone cancer.

The doctor and the veterinarian — seeing firsthand the value of their collaboration — spearheaded fund-raising for the chair endowment to ensure that future medical professionals will continue cooperative discoveries to save limbs.

“It’s a great honor to hand it off to you,” Withrow told Ehrhart when they recently conferred in her lab. “I hope I’m alive long enough to see who you hand it off to.”

Ehrhart’s Laboratory of Comparative Musculoskeletal Oncology and Traumatology epitomizes “translational medicine,” in which findings from research into animal disease are applied to human medicine. She has been actively involved in limb preservation research, regenerative medicine, tissue engineering and sarcoma research for the last 18 years.

Dr. Rod Page, director of the Flint Animal Cancer Center and holder of the Stephen J. Withrow Presidential Chair in Oncology, affirms the endowment’s role in securing the future of limb-sparing research.

“I often say, ‘Cancer is cancer – it doesn’t care what species you are.’ This chair will allow Dr. Ehrhart, and others who come after her in perpetuity, to pursue research that will help save human and animal lives,” he said.

Ehrhart described her appointment to the chair as the pinnacle of her career.

“I’m a veterinarian and I love animals, but I have a great sense of excitement about helping people, too. The greatest thing for me is the opportunity to do both,” she said. “The greatest reward of this chair is that I have the opportunity to make an impact in both worlds.”

Studying disease in dogs provides a fast-track option that saves money and time in moving research discoveries to patients, whether they are four-legged or two-legged. That’s because dogs age faster than humans, meaning they develop disease and respond to treatment in less time.

“To get any new treatment on the market, from laboratory to the patient, it takes 15 to 20 years and somewhere around $12 billion,” Ehrhart said. “The truth is that people who have these types of threatening diseases don’t have that time. They needed our help yesterday. They can’t sit around and wait for this to happen.”

Researcher, teacher, doctor

Ehrhart certainly isn’t sitting around waiting.

On a typical day, she checks on mouse cells in her lab on the second floor of the Flint Animal Cancer Center, then heads downstairs to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital for case discussion, or rounds, with 15 oncology residents, students and other veterinarians.

One recent day, discussion centered on the difficult questions that arise when a pet is diagnosed with cancer. Ehrhart helped gently lead the reluctant students into a mental health discussion. “I’ve had clients share suicidal thoughts. That’s a scary thing,” she told the room. “I say, ‘Thank you for telling me,’ and I offer them resources. As medical professionals, we have an obligation to help.”

After morning rounds, Ehrhart and a student met with a client whose Basset hound was headed home after successful surgery. After making sure the dog had the right-sized protective collar, she crossed the hospital to the diagnostic imaging center to see another surgical patient’s chest radiographs and was cheered to see the lungs were clear.

Next came surgery. Dressed in blue scrubs and a purple cap, Ehrhart might be hard to pick out in the surgical suite. But two features, in addition to her expert calm, make her stand out: She’s 5 feet 1 inch tall, and a bedazzled gold lanyard peeked out from her V-neck surgical top.

By the end of the day, she was ready to check in with her two teenaged daughters and perhaps enjoy a glass of wine with her husband and friends. In her time off, she is often in the mountains, backpacking or skiing.

A change of plans

After Ehrhart earned her Doctor of Veterinary Medicine from the University of Pennsylvania in 1990, she came to CSU for a residency and fellowship in surgical oncology under Withrow[4]. Ehrhart thought she would go into private practice as an orthopedic surgeon, but three things happened to change her course.

“First, I went to cancer camp and met kids fresh out of amputations. At the same time, I was learning about limb-salvage surgery with Dr. Withrow. I kept wondering why we could save legs in dogs, and we were amputating legs in kids,” she recalled.

She began to see the impact of translational medicine, and her mentor, renowned CSU orthopedic surgery professor and textbook author Dr. Don Piermattei, reinforced the importance of finding meaning and balance in one’s work. “I asked him about his greatest impact, and he said, ‘When I look back on my life, I think about the people I taught, the people who came after me. I think about the kind of father and husband I was,’” said Ehrhart, her voice cracking. “I thought, ‘I need to think about that.’”

The third element of her career shift: “I was starting to see the whole impact of translational medicine and how animals impact human health. I said, ‘I have no business being in private practice. I need to stay here.’ So I stayed in academia.”

She joined the faculty of the University of Illinois in 1996, and CSU recruited her back in 2002 for the opening of the new cancer center building. She is now a professor of surgical oncology, with 62 peer-reviewed publications, in addition to running the Laboratory of Comparative Musculoskeletal Oncology and Traumatology.

Ehrhart also holds joint faculty positions in the CSU School of Biomedical Engineering and the Cell and Molecular Biology program. She is a member of the Gates Regenerative Medicine Center at the University of Colorado and the University of Colorado Cancer Center.

Looking back, she credits Withrow for seeing something in her that she did not yet see in herself: “I came here as this little resident that thought I wanted to go in one direction. Then I met Steve, and he lit some kind of fire in me that lasted the rest of my career. I am now carrying a torch that I never expected, and I have so much passion for. I hope to light that fire in someone else.”

That spark has touched Kaitlin McNamara, 25, a second-year veterinary student who works in Ehrhart’s lab. “Dr. Ehrhart turns everything into a learning experience,” McNamara said. “She was there as a mentor when I needed her, but she let me grow into my role as a researcher as well.”

The student becomes the teacher

[5]

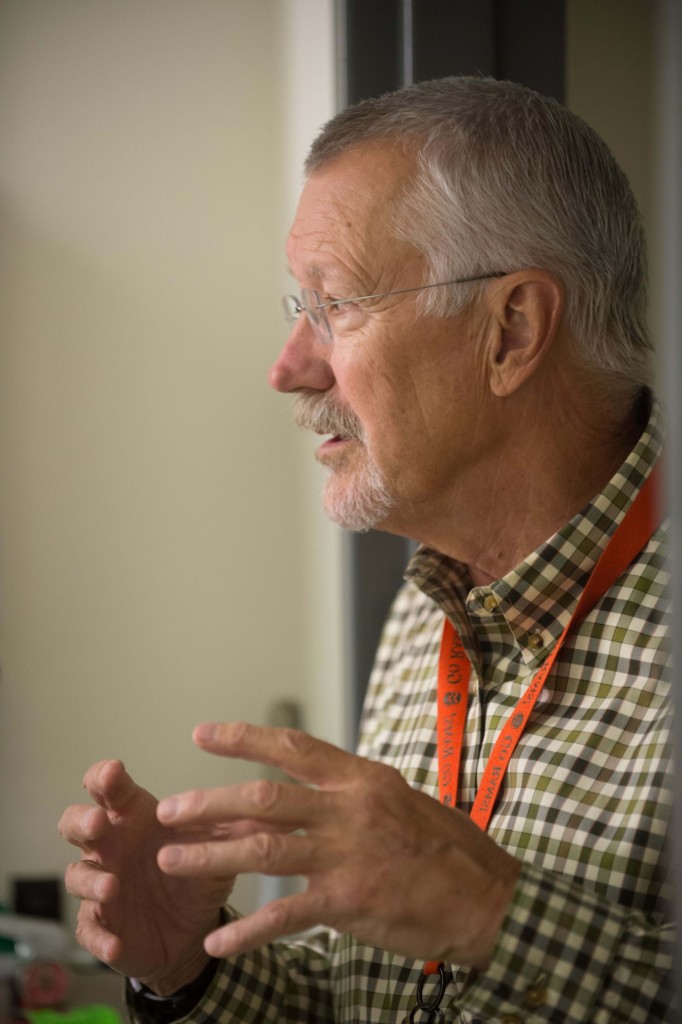

[5]Ehrhart and Withrow spent some time together in the lab recently, looking at cell cultures and talking about the history and the future of their cancer research. At 68, Withrow is semi-retired but keeps an office in the cancer center that he started with Dr. Ed Gillette in 1984.

Ehrhart, 49, is following in Withrow’s footsteps in many ways, in addition to walking the halls of the Flint Animal Cancer Center at CSU. Every summer, she volunteers with him at the Sky High Hope Camp[6] for children with cancer. In fall 2014, she was inducted into the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society, just the second veterinarian to earn this recognition, after Withrow. They are both founding fellows in surgical oncology within the American College of Veterinary Surgeons. She sits on the board of the Limb Preservation Foundation, which Withrow, Wilkins and others founded.

“He has children of the soul – and one of them would be me,” Ehrhart said. Then she turned to Withrow and added, “I always feel like my feet are so tiny compared to the footsteps that you have already left to me. For me, it is really like standing on the shoulders of giants.”

As Ehrhart explained an experiment, Withrow seemed as wowed as a lay person might be.

“We’re not just interacting on a mechanical level with the body, not just replacing body parts with new mechanics. Beyond the cellular level, we are working with the sub-units of biology and nano-technology. That’s opening up an entire new world with the ability to change how cells interact, how the body is able to heal,” she said. “It gives me goosebumps because we are going to make leaps forward in the next 10 years in keeping people and animals whole.”

Withrow marveled at strides in cancer research since he and Wilkins[7] first collaborated on limb-sparing techniques in the 1980s.

“Who’da thunk that you could move muscle from patient to patient and have it function? It’s like ‘Star Wars’ technology,” Withrow said to Ehrhart.

Thanks to the endowment symbolized with the Wilkins University Chair, Ehrhart will be able to continue the research, paying it forward to the next generation of students and patients.

“The chair ensures not only that this research will continue in perpetuity, but that this forever links the human side and the animal side. This is a permanent bridge, and there is no other program like it that links these two areas,” she said. “The chair allows us to keep pressing forward, to ask the next question.”

Comrades in Cancer Establish a Standard of Care,

and an Endowment

Like many visionaries who seize inspiration in unlikely settings, Dr. Stephen Withrow, veterinarian, and Dr. Ross Wilkins, physician, sketched their limb-sparing surgery ideas on the nearest available surface.

“A lot of the early ideas were written on napkins at pizza parlors. You gotta get it down,” said Withrow, whose folksy manner belies his stature as an international leader in cancer treatments for animals and people.

[8]

[8]In the early 1980s, Withrow and Wilkins were both starting cancer programs in Colorado. They became friends and collaborators, meeting for dinner to brainstorm about the topic that absorbed them: bone cancer. Both had trained at the Mayo Clinic, and they were asking the same question: “Can’t we do something with the leg and the arm rather than cutting them off?” Withrow recalled.

Hard as it is to believe, “limb preservation for bone cancer as a treatment was just starting,” Withrow said. “Before the ’80s, almost all the kids died.” Dogs with osteosarcoma died, too. There was not an accepted standard of care, other than amputation, and even that was unusual in the veterinary world. “At the time, surgery was wholly underrepresented in veterinary oncology, and I saw that we needed to standardize surgical oncology care for pets with cancer,” Withrow said.

Withrow and Wilkins knew there had to be a better way.

Over the next four decades, the two forged a professional collaboration in orthopedic oncology that has led to thousands of limb-sparing surgeries in animals and humans. Their partnership has helped solidify translational oncology, the combined effort to improve cancer treatments for pets and people. And now – with the appointment of Dr. Nicole Ehrhart to the Ross M. Wilkins, M.D. Limb Preservation University Chair in Musculoskeletal Biology and Oncology – the veterinarian and the physician have helped to formally ensure that their work continues.

Similar paths, different species

Early in his veterinary career, Withrow was an intern at the Animal Medical Center in New York City and pursued his interest in cancer by observing rounds at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. An unusual fellowship (for a veterinarian) at the Mayo Clinic affirmed his desire to build a surgical oncology program in veterinary medicine.

[9]

[9]He came to Colorado State University in 1978 with that in mind, and with the support of pioneering radiation oncologist Dr. Ed Gillette[10], pitched his vision to college leaders. “After three years as a general surgeon, I approached the department head for permission to develop this new service that would allow us to provide the care needed for cancer patients, allow us to do translational trials, and would enable us to embrace research. In only two years, we created a stand-alone clinical oncology service,” Withrow said[11].

Wilkins was on a parallel path, looking for better ways to treat children with bone cancer.

“In those days, you’d do the biopsy and you’d do an immediate amputation and wait for these kids to die. Over 90 percent died,” Wilkins said. He remembers a key moment with his mentor, Dr. James Miles, at the University of Colorado Medical School. “I’ll never forget I used to stay late looking at slides under the microscope, and we were both almost in tears about how sad it was. He looked me right in the eye and said, ‘This is your problem to solve.’”

Wilkins took up the challenge and headed to the Mayo Clinic for an orthopedic oncology fellowship, returning to Denver to found The Denver Clinic for Extremities at Risk[12] to treat patients. In 1986, with the late Dr. Tom Arganese, Wilkins started The Limb Preservation Foundation[13] to raise funds for research, education and patient assistance.

By this time, Wilkins and Withrow had become friends, realizing they were chasing answers to the same problems. The veterinarian and the human doctor hypothesized that naturally occurring bone cancers in dogs were similar to bone cancers in people, making dogs a relevant model in which to study osteosarcomas in both species.

“Even then the prognosis was terrible, very bleak,” Wilkins recalled. “We started pushing forward with chemotherapy after surgery, then we started using chemo before surgery and developing innovative ways to get the cancer out and still save the limb. That’s been the mantra – not only the limb preservation, but survival. For many years, it was thought to be experimental. But in the late ’80s, we came to a national consensus, and it has now become the standard of care world-wide.”

Making strides in surgery

A key contributor to that consensus was the work at CSU, funded largely by the National Cancer Institute. “We were looking at bone cancer in dogs as a model for humans, ways to give the chemo pre-operatively. We proved it was safe in animals, and we proved that it took a big tumor and made it into a small tumor. It converted the inoperable into operable,” Withrow said.

The first limb-sparing surgery in a dog was performed at the CSU Veterinary Teaching Hospital in 1985 on an Irish setter named Cobb, who came from Chicago for the innovative new procedure. “It took us 14 hours – we saved every tendon, every vein,” Withrow said. “Cobb set the stage for about 600 surgeries that came after.”

And Wilkins’ Limb Preservation Foundation set the stage by funding clinical and laboratory research into osteosarcoma and fracture treatments, chemotherapy and disease transmission during bone and tissue transplants.

By 2000, Wilkins’ and Withrow’s innovative approaches to research and their unusual professional bond caught the eye of the news show “20/20,” which produced an 11-minute segment[14] on the pair’s research and relationship. “I personally learned a lot from him related to my human practice,” Wilkins said in the piece. “There’s an old saying in medicine, ‘People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.’ I think that exemplifies Steve Withrow.”

Withrow’s admiration is similar. He recently said of Wilkins: “I think our mentalities are the same, that we care about patients, that curing and caring go hand in hand. There’s a lot of work to do, and we can do it better together than alone.”

Seeking sustainable funding

They had proven the science. Children and dogs with bone cancer were surviving, with limbs intact and cancer-free. The next challenge was to ensure a steady source of research funds.

Just as Withrow and Wilkins refused to accept the status quo in osteosarcoma treatment, they began to question research funding models. The Limb Preservation Foundation, whose mission is to support the prevention and treatment of limb-threatening conditions due to trauma, tumor or infection, has funded a variety of projects at CSU and around the world, but its leaders have an even larger vision.

“We started to ask, ‘Can’t we do something bigger and more global? What are the obstacles to continued research?’” Withrow said. “Problem is, the funding comes and goes. You fund your lab, your post docs and graduate students, and then you don’t have funding. I said, ‘We have a future in the study of sarcoma and musculoskeletal disease, but we are limited in sustainable funding.’ The way to get around that is to endow a chair.”

The foundation agreed, and began raising funds toward a $3 million endowment for a university chair. Half would be funded by the foundation, with a lead gift from tissue bank AlloSource[15] and the McDonnell Family Foundation, and half would be funded by the CSU Flint Animal Cancer Center.

“It took us 10 years,” Withrow said. “I think it’s unique that we had enough trust between the two organizations to raise that kind of money. The whole 30 years has been built on the trust that we can make life better for animals and people.”

Passing the torch

Now Withrow, 68, and Wilkins, 64, are assuming grandfatherly roles as they marvel at the progress of their protégés, particularly Dr. Nicole Ehrhart[16], who has been named to the Ross M. Wilkins, M.D. Limb Preservation University Chair in Musculoskeletal Biology and Oncology.

[17]

[17]The title is a little embarrassing for its namesake. “Steve keeps calling it the ‘Wilkins Chair,’ but it’s really the Limb Preservation Chair. It’s a huge group of people who have supported us all these years,” Wilkins said. “I was in tears when I found out Nicole got the chair.”

When asked about Ehrhart being the first woman to hold a university chair, one of CSU’s highest honors, Withrow was plain-spoken as ever: “It’s time for some gender equity around here. I think we should all be proud of it. Early on, Nicole showed an interest in bone cancer and tissue grafting and molecular approaches to oncology and bone healing that exceeded what Ross and I brought to the table. That’s what you want – for your kids to be better than you are.”

Ehrhart acknowledges the responsibility for succession planning; she has mentored 22 fellows so far in her career, with more to come. “It’s now my job is to make sure that whoever comes after me does something bigger and better than I could ever have done. So my job is to teach everything I can to those under me so they can go on to do greater things. That’s how legacy continues, and I had great examples,” she said.

The work happening in Ehrhart’s lab dazzles her mentors. “It’s much more scientific than what Ross and I started with. We started with carpentry and now we’ve moved into – Ross called it gardening – but it’s really biology, and it’s just a whole new world,” Withrow said. “Ten years ago, nobody had the slightest idea that you could transplant muscle. That wasn’t part of the scheme that we did. We transplanted bone, tendons, ligaments, cartilage. But now, any tissue, and almost any organ, is possible to move from patient to patient effectively – legs, hands, faces, nothing’s impossible.”

About the Limb Preservation Foundation

The mission of the Limb Preservation Foundation is to support the prevention and treatment of limb threatening conditions. The goal of the Foundation is to enhance the quality of life for those individuals facing limb-threatening conditions due to trauma, tumor or infection through research, patient assistance and educational programs.

The Limb Preservation Foundation funds life-changing research that is accelerating improvements in treatments and outcomes for patients at risk of losing a limb. Research funded by the Limb Preservation Foundation has led to an increased survival rate of bone cancer patients from 60 percent to 94 percent, and enabled 95 percent of patients to keep their limbs. To ensure the sustainability of research efforts, through collaboration with Colorado State University Flint Animal Cancer Center, the foundation has established The Ross M. Wilkins, M.D. Limb Preservation University Chair in Musculoskeletal Biology and Oncology.

About the Flint Animal Cancer Center

The Colorado State University Flint Animal Cancer Center’s mission is to improve the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of cancer in pet animals, translating research and knowledge to also benefit people with cancer. The center offers the latest and most advanced diagnostics and treatments in surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy. It attains its mission through an innovative study of cancer, thoughtful and compassionate care, specialized treatment options and procedures.

The Flint Animal Cancer Center continues to pursue a cure for cancer through its clinical oncology service, clinical trials, advanced clinical and research training for veterinarians, innovative research and specialized consultation service available for clients and referring veterinarians.

About AlloSource

AlloSource, one of the nation’s largest providers of skin, bone and soft tissue allografts for use in surgical procedures, and the world’s largest processor of cellular bone allografts, pledged the lead gift to the Ross M. Wilkins, M.D. Limb Preservation University Chair in Musculoskeletal Biology and Oncology. The McDonnell Family Foundation and the Ferguson Family joined the campaign as major sponsors, along with many generous supporters of The Limb Preservation Foundation. Colorado State University’s Flint Animal Cancer Center matched each dollar raised to fund the chair.

Media Assets

Photo

Click to enlarge photos in story

Video

Full package, no titles[18]

B-roll

- Dr. Nicole Ehrhart: http://www.cvmbs.colostate.edu/DirectorySearch/Search/MemberProfile/cvmbs/1013/Ehrhart/Nicole

- [Image]: http://source.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/ehrhart.body1_.jpg

- Flint Animal Cancer Center: http://www.csuanimalcancercenter.org/

- Withrow: http://csu-cvmbs.colostate.edu/Pages/withrow-stephen-distinguished-professor.aspx

- [Image]: http://source.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/ehrhart.body2_.jpg

- Sky High Hope Camp: http://skyhighhope.org/

- Wilkins: http://limbpreservation.org/about/who-we-are/wilkins-story.html

- [Image]: http://source.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/withrow.1.jpg

- [Image]: http://source.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/withrow.2-copy.jpg

- Dr. Ed Gillette: http://csu-cvmbs.colostate.edu/Pages/gillette-edward-obit.aspx

- Withrow said: http://www.csuanimalcancercenter.org/fs-dr-withrow

- The Denver Clinic for Extremities at Risk: http://pslmc.com/service/the-denver-clinic

- Limb Preservation Foundation: http://limbpreservation.org

- 11-minute segment: https://youtu.be/9dobC6bpcjU

- AlloSource: http://www.allosource.org/

- Dr. Nicole Ehrhart: http://www.csuanimalcancercenter.org/fs-dr-ehrhart

- [Image]: http://source.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/withrow.3.jpg

- Full package, no titles: https://vimeo.com/136527966

Source URL: https://source.colostate.edu/legacy-for-3-million-professor-earns-funding-for-musculoskeletal-trauma-and-cancer-research/

Copyright ©2024 SOURCE unless otherwise noted.