CSU President Tony Frank, thinking he would “dig up some nuggets from his vitae,” recently prepared to introduce Dr. Wayne McIlwraith at a campus event by printing the pioneering veterinarian’s academic resume.

“One thing I discovered is that I do not know how to shut off the print function on the big printer in our office,” Frank jokingly told a crowd gathered this spring for McIlwraith’s talk during the President’s Community Lecture Series. “It is a CV that goes on for well over a hundred pages.”

Most recently added to that curriculum vitae: namesake of the C. Wayne McIlwraith Translational Medicine Institute. A ceremony on June 2 will mark groundbreaking for the institute on CSU’s South Campus.

McIlwraith is a trailblazer in equine arthroscopic surgery and research in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of joint injury and disease in horses. Many of his discoveries have informed advances in human orthopaedics.

He is a University Distinguished Professor in the CSU Department of Clinical Sciences and is founder of the Orthopaedic Research Center. McIlwraith holds the Barbara Cox Anthony University Chair in Orthopaedics and is director of the Musculoskeletal Research Program, a CSU Program of Research and Scholarly Excellence.

His research interests focus on equine orthopaedic surgery and joint disease research, including novel treatments for osteoarthritis and articular cartilage repair, mesenchymal stem-cell and gene therapies, and early diagnosis of osteoarthritis and pre-fracture disease using imaging and fluid biomarkers.

McIlwraith has authored six textbooks, 450 scientific publications and textbook chapters, and has delivered more than 650 scientific presentations, seminars and workshops.

As the university prepares for construction of the Translational Medicine Institute, we asked its namesake about the past, present, and future of his work.

Let’s go back to the beginning of your career. You were raised in New Zealand and educated in your home country, Canada, and the United States. How did you become interested in veterinary medicine and orthopaedic surgery?

I was brought up in the South Island, in a small town in New Zealand. But I spent quite a lot of my school holidays at my aunt and uncle’s high country sheep station in New Zealand. They had cattle and sheep, and it’s relatively remote. I thought the lifestyle was great, and when the vets came up, I thought it was a really interesting career. My aunt also rode and competed at show jumping. She taught me to ride which transitioned me from looking at race horses to actually riding horses, and I was hooked. I also spent time, as a high school student, in one of the local veterinary practices. I made the decision to pursue veterinary school at Massey University in New Zealand. I was interested, initially, in large-animal practice – sheep, cows, and horses. And I actually worked in a mixed-animal practice for two years after I graduated, with a lot of surgery involved, because of sheepdog injuries. That was my start in orthopaedic surgery. Sheepdogs get a lot of cruciate ruptures and bone fractures.

I left New Zealand in March 1973 leading a climbing expedition in the Peruvian Andes. After three months climbing and three months traveling in South America, I went to England and worked as a locum tenens (relief veterinarian) in a large-animal practice in Wales for six weeks and a small animal practice in the east end of London for about four months. Then after three months climbing in the European Alps I started a one-year internship at the University of Guelph in Canada. At that time, surgeons were starting to save horses with colic. So the first thing that attracted me to equine surgery was the challenge of fixing horses with twisted bowels because many horses with colic were euthanized at that time. The internship involved all facets of equine surgery including orthopaedics and lameness and I became excited about all these pursuits. I decided, “This is what I want to do.” So I applied for residencies and got a residency at Purdue University in Indiana, and now I was certainly proceeding down the road of a commitment to specialty surgery.

What drew you further into work with horses? And, ultimately, why did you view the horse as an ideal model for orthopaedic research, specifically in surgery?

My internship at Guelph was in large-animal surgery, principally horses. I found that I enjoyed working around horses, and I worked well with horses. My initial goal when I went to Purdue was to be trained as a specialist in equine surgery. My advisor and mentor, Dr. Jack Fessler, gave me a research project in synovitis, inflammation of the lining of the joint, as part of my master’s degree, which we did simultaneous with the residency program. This was a really critical juncture for me because two things happened.

First of all, I was working with an experimental model of synovitis and started to read the literature, which was virtually nonexistent in the horse. This was 1975 to ’76. The human literature on osteoarthritis was also quite confusing. It was like the arthritis just happened, and any inflammation you saw was secondary. What we showed in this study was that if you inflamed a joint and you did nothing else – you didn’t destabilize it or cause physical trauma – you could still get cartilage degradation. That was contrary to medical thinking in humans, and as I said, there wasn’t much literature on the horse.

Then Dr. David Van Sickle asked me if I’d continue the work into a Ph.D., in the same model, but looking at more outcome parameters and more questions. So I got very good training in joint disease because he had done so much research on the pathology of joints and established the Bone and Articulation Research Laboratory in the Purdue School of Veterinary Medicine. Much of his work was in canine joints, so I had the opportunity to learn a lot from him and to take it into the horse. And it was a big opportunity, because there’d been hardly anything done.

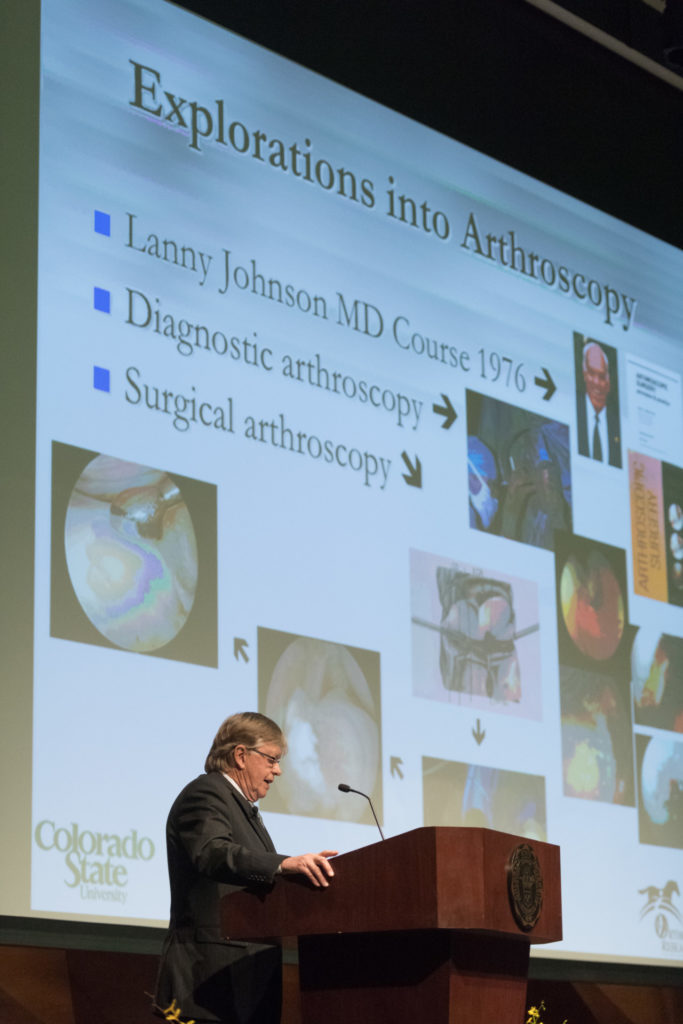

The second thing that was pivotal for my career was that I read about the arthroscope. The arthroscope was just beginning to be used as a diagnostic tool in humans. The state-of-the-art then was that if you had knee pain, you had an arthrotomy and your meniscus was taken out, based on the positioning of the pain. This was before MRI, as well. Dr. Lanny Johnson, who was a professor at the medical school at Michigan State, was having a course in diagnostic arthroscopy. And I guess I was cheeky enough to call him up and say, “I’d like to come to your course. I’m a veterinary surgery resident, not a human surgery resident.” And he said, “Oh, it’d be great to have you. Come on up. I won’t charge you a registration fee.” So I drove up to Michigan State University, and a couple hundred medical doctors and I learned how to do a diagnostic arthroscopy of the human knee.

So I went back, and Purdue bought me an arthroscope so I could do diagnostic arthroscopy in analogous fashion to what they were doing in humans. I finished my Ph.D., and I’d done a lot of arthroscopy, but just diagnostically. Then I got the job as an assistant professor at CSU in 1979.

That’s when I started, with the help of a human orthopaedic surgeon, Dr. Ron Grober, who visited me from Florida for a day, and got me started in developing triangulation techniques to do surgery. So, in other words, rather than just look, we were working to perform the surgical manipulation and a visualization with the arthroscope. Those were the early days, when we were looking at the joint directly through the scope, and human orthopaedists were doing it the same way. Those were early, pioneering days, and there was resistance to the technique both in human medicine and in the horse.

So I came to CSU equipped with a reasonable knowledge of joint disease. Plus, I had started using the arthroscope. Then we developed the surgical techniques. So my career has involved a research pathway and a clinical pathway. And, of course, they both join together.

Much of your clinical path has involved racehorse patients. How and why did you gain an affinity for racehorses and working with those patients?

Well, it was more a case of them getting affinity for me, because I had a technique that most other equine surgeons were not doing yet. I came here in August 1979 as one of four surgeons. Dr. Simon Turner soon got engaged in arthroscopic surgery here as well. By 1981, we had developed techniques to arthroscopically remove carpal chip fragments. We could also take chip fragments off the front of the fetlock joint arthroscopically. These were the two main surgical conditions in racehorses. So horses started coming here from 10 surrounding states. There were a couple of doctors doing some arthroscopy on the East Coast, but nobody else in the West. So we would get horses from Utah, Nevada, California, Nebraska, Kansas, Wyoming, Montana. There was strong racing in a number of those states at that time.

Starting in 1983, Dr. Turner and I started giving six arthroscopic surgery courses a year, and we could only take 12 people at a time because we’re looking through the arthroscope – it was before we had video cameras – so it was very laborious.

Dr. Nancy Goodman, who was a CSU veterinary graduate, was in a racetrack practice in California, and she couldn’t get into one of our courses because they were booked up. So she asked me to come down and do surgery on a couple of horses. I flew down to their clinic, and we operated four horses and got done at 2 in the morning. And then she had me back the following week for another four. And then I went for a weekend, and I ended up marrying Dr. Goodman. That started my surgical referral practice in Orange County, California. The first 16 years that Nancy and I were married, she worked eight months a year in California, and I was down there every other weekend doing surgery. When Nancy retired from racetrack practice after 20 years, in 2001, surgical practice continued with her as my primary assistant.

Fast-forward to now. A lot of horses that undergo arthroscopic surgery here in Colorado are American Quarter Horses in Western performance disciplines. In the early days, we didn’t have the techniques to treat stifle injuries, which are often seen in Western equine athletes, such as cutting horses and reining horses. The stifle, which includes the femoropatellar and femorotibial joints, was the endgame because doing surgery on femorotibial joints, in particular, was more complicated. We developed a technique for femoropatellar joints and published it in ’86, but femorotibial joints came along after that.

Other techniques came pretty quickly with multiple techniques quickly developed by other equine arthroscopic experts in addition to our group. In the early ’80s, I certainly would not have predicted how far we would go with arthroscopic surgery and that we would be able to treat many racehorses for their injuries and have them come back to full athletic ability. Because of their multiple injuries, the racehorse became the poster child for arthroscopic surgery. But it is now a powerful tool for treatment of joint injuries as well as problems of the tendon sheaths and bursae in all breeds.

A lot of people who get involved in racehorses are brought up with them. I wasn’t, but I was always fascinated by racehorses. I used to bike up to the racetrack in my hometown of Oamaru when they had a meet. My mother didn’t like it because that was gambling, and she was a good Presbyterian. But I was always fascinated by it. I got heavily involved in the racing industry, both racing Quarter Horses and racing Thoroughbreds, by virtue of operating on them. I love it, and I’m passionate about it. I still do surgery on them. For a long time, Nancy said the only way I liked horses was when they were on their backs with surgical drapes on them! I think she retracts that now and we currently have 12 horses at home. But anyway we did revolutionize things for racehorses with arthroscopic surgery in similar fashion to human orthopedics.

Arthroscopic surgery for equine athletes was the biggest revolution at the time in being able to treat musculoskeletal problems and get them back to their previous level of racing. While we developed a lot of the techniques for arthroscopic surgery, other equine surgeons did their share as well. We put on our first advanced arthroscopic surgery course at CSU in 1988, and we became the place where most veterinarians came to learn it. Our textbook on “Diagnostic and Surgical Arthroscopy in the Horse,” whose fourth edition was published in 2015, has 454 pages reflecting the evolution.

You mentioned that, going back to childhood, you were fascinated by racehorses. Why? What about them have you found so captivating?

Well, they are beautiful. And you see them with the jockeys dressed in their colors. It was fascinating, the whole thing – and the speed and the excitement. Horse races were much better attended when I was growing up. In New Zealand, at that time, every race from across the country was on the radio on Saturdays. This was pre-television – we got a black-and-white TV at home in my last year of high school. It was just like the days of Seabiscuit over here. Thousands of people went to the races – it was a real happening.

So let’s fast-forward. Set the scene for us, in 1979, you’re being interviewed to come to CSU. Whom did you interview with? What drew you to CSU? And what did you hope to accomplish here?

I interviewed here in 1979, and they had just opened the Veterinary Teaching Hospital on Drake Road. It had been open for two weeks. And Dr. Jim Voss was head of the Department of Clinical Sciences. He had me stay at the Thunderbird Motel on the corner of College and Drake. The vet hospital was basically the only place on Drake that existed. Dr. Voss had a two-day interview process. You talk to everybody, and you give a seminar.

Then Dr. Voss was taking me to dinner with three other faculty members, including Dr. Simon Turner, who had been counseling me to shave off my beard, which I had at the time. So Dr. Voss picked me up in his pickup truck, and he was chewing tobacco, and I soon figured out I was in real cowboy country in the West. And he says, “OK, we’ve got 10 minutes for you to tell me what you think, what you like, what you don’t like, and then we’re going to get drunk.” Well, it wasn’t badly drunk, but we had a great dinner at the Prime Minister, and drinks certainly loosened things up.

During dinner, Dr. Voss asked, “Why did you shave off your beard?” He had been at a meeting where I’d spoken three months earlier. I said, “Well, Dr. Turner told me I couldn’t communicate with you guys with hair on my face.” He says, “Oh, that’s no problem.” And I said, “Well, I’ll grow it back then.” And Dr. Bob Shideler said, “Oh, it would be good if you didn’t, Wayne.” That’s one of the two main things I remember about the interview. The other main memory was how much I wanted to get the job at CSU. I did get offered the job as an assistant professor, and I arrived in August 1979, still clean-shaven.

You’re known at CSU as a University Distinguished Professor of Orthopaedics and as founding director of the Orthopaedic Research Center. But you’ve worn other hats through the years, including director of the undergraduate program in Equine Science. Tell us about those other roles.

That came about in 1994, when I’d been here 15 years. Dr. Bill Pickett started the Equine Sciences Program, which consisted of the undergraduate program in Equine Science and the Equine Reproduction Laboratory, and then he retired. Dr. Voss had become dean, and he was quite visionary. They had a search open for the new director of the Equine Sciences Program.

Dr. Voss called me and said, “I want to talk you into taking over Equine Sciences.” That would mean taking over the undergraduate program and the Equine Reproduction Lab. But he also said, “I want you to build the biggest equine orthopaedic research program there is.” His plan was to replace me in the clinic and give me a tenure-track position in research as well. Nancy and I discussed it, and we decided it was a good opportunity if I was going to move forward. I wanted to continue surgery, and that was no problem because of my practice in Southern California.

So for seven years, I was in charge of all three programs. I was building up the Orthopaedic Research Center and was director of the Equine Reproduction Laboratory, as well as the Equine Science undergraduate program. Then the Orthopaedic Research Center developed a critical mass, and I wanted to devote all my time to that. So that’s how I had a seven-year swing through Equine Sciences.

You’re an international pioneer in arthroscopic surgery and joint disease research in horses. And you’ve been honored many times by academic colleagues and others. As you survey your career, what do you consider your biggest achievement?

Am I allowed two?

Yes.

Well, pioneering arthroscopic surgery in the horse has been an achievement, along with teaching a lot of people how to do it, and writing the book on it (“Diagnostic and Surgical Arthroscopy in the Horse,” in its fourth edition). And the second is developing the Orthopaedic Research Center. It started as the Equine Orthopaedic Center, but because of research grants from the National Institutes of Health and corporations, we’ve just left it as “Orthopaedic Research Center.” That’s how we’ve got where we are now.

What do you consider to be your biggest, most important research breakthroughs or innovations?

Well, they build on each other, as research does. Going back to my Ph.D. work, even though it’s just one paper in the veterinary literature, recognizing the critical nature of synovitis actually turned out to be very important long-term for translational purposes. At the time, human doctors emphasized that osteoarthritis was not inflammatory, which seemed a bit strange, because it certainly was in the horse. Understanding that led into evaluating different treatments for the synovitis, and thereby making a lot of horses better. It has been important to validate the various treatments in joint disease as good, bad, or otherwise – and that is all part of the recognition of synovitis.

Another big breakthrough was the gene therapy work that Dave Frisbie did with me for his Ph.D., in collaboration with Christopher Evans, who was at the University of Pittsburgh and then moved to Harvard. We showed that interleukin 1 was the bad guy and that the equine interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene, which is a natural antagonist, would shut down inflammation in the joint, and the consequent osteoarthritic change. This work was our first venture into the world of biologic therapies.

Our cartilage healing research has been important, along with use of the horse as a model for cartilage repair in humans. Early diagnosis of musculoskeletal disease, because of the drastic consequences that you can have with catastrophic injury, is a huge part of our work. This started with Dr. Chris Kawcak’s Ph.D. studies with Dr. Bob Norrdin and myself showing how quickly microdamage could develop in the exercising horse and that this was the initial event in osteochondral fractures. While this microdamage could be displayed in pathology samples, we needed to be able to diagnose it before it became a critical fracture in the horse. We have made considerable progress in identifying imaging biomarkers, including nuclear scintigraphy, computed tomography, and MRI, as well as fluid biomarkers that we can pick up in the serum. This area is still a work in progress but has got the best potential of predicting catastrophic injury compared to other techniques.

The two biggest breakthroughs in sports medicine, whether it’s horse or humans, are arguably arthroscopic surgery – and now biologic therapies. That’s where we are now, as we transition into the Translational Medicine Institute. These are therapies that have minimal side-effects and take us to a newer level. They include proteins, cellular therapies, and stem-cell therapies. We have taken a problem that we treat arthroscopically, and we’ve been able to raise our success rates significantly with the additional use of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. It’s a big focus for us.

Continuing this path of discussion, define translational medicine.

It’s the use of basic laboratory research, preclinical research in vivo, and clinical examination that leads to patient success – with what we learn in animals often translating into improved medical treatment in humans. The outcome is better diagnosis and better treatment of the patient, whether animal or human.

What do you see as the role of biomedical research and veterinary medicine in the process you just described? Essentially, what is the unique contribution of veterinary medicine in that spectrum of discovery and improved care?

Well, at the present time, you’re never going to get a medication or a biologic technique validated and licensed for use in humans until you do good preclinical research in animals. So, pragmatically, you’ve got to have preclinical work conducted by veterinarians in animals before you can get it into humans. Additionally, many diseases that occur naturally in people also occur naturally in animals. That makes veterinary research and clinical treatment important in advancing human medicine: When we join our efforts and join our discoveries, we find more effective treatments more quickly.

Here, we’re interested in musculoskeletal disease and injuries – osteoarthritis, cartilage injury, tendon injury. The horse gets these naturally, as does the person. With cancer, the dog is the translational starting point, because they develop so much cancer during the course of their lives, just as humans do.

So veterinary medicine is critical, and it’s recognized a lot more, too. In the old days, it was like, “Well, animals are different than people.” You’ll still get some pedantic souls who talk like that, but there are lots of parallels.

Did you have an epiphany sometime during your education or your career, when you realized, “This work I’m doing could have far-reaching implications, not only for animal health, but for human health”?

It’s been more of an evolution. I learned how to use an arthroscope from a human orthopaedic surgeon. After that, we developed the techniques in equine arthroscopic surgery. We got into inflammation and recognizing the importance of synovitis through study in the horse. Now, there’s lots of papers in human medicine on the critical nature of primary synovitis and primary subchondral bone disease, something that we’ve known ever since we started clinically treating horses and have also defined more closely with research. We’ve always felt that many findings in horses could be extrapolated to humans.

We started working with Dr. Richard Steadman at the Steadman Clinic and Dr. Bill Rodkey at the Steadman Philippon Research Institute in Vail because they wanted us to validate the use of microfracture as a surgical technique to repair damaged areas of articular cartilage of the knee. After that, we had corporations coming to us to test treatments in the horse, and later worked on quite a number of grants from the National Institutes of Health with us doing pivotal pre-clinical studies in the horse.

What do you think of as a best example of work you’ve done in the horse that has been applicable to human musculoskeletal disease?

We have worked collaboratively with experts in biomarkers in osteoarthritis. From that, we have developed biomarkers to predict early osteoarthritic change in the horse that also have a fairly good probability of predicting catastrophic fracture, or at least significant musculoskeletal injury, in the horse.

We worked with Chris Evans, who is arguably the father of gene therapy in human orthopaedics, on the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist research. He pointed out that, for the first time, we showed with gene therapy we could get a clinical response close to a cure for osteoarthritis.

Our results with mesenchymal stem cells have been very impressive in the horse. The proof of principle has been accomplished. The optimal use of these cells given the current regulatory standards, including the need to ensure safety, is an evolving challenge. But we’ve been able to prove the value of these therapies, and stimulate further developmental efforts in human medicine. Our efforts are certainly a small part of the overall human landscape, and people such as Dr. Arnold Caplan at Case Western pioneered the work in bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells starting over 20 years ago. The advantage of the horse is that we’ve been able to do clinical studies and get good proof of principle of how they can significantly enhance our ability to treat osteoarthritis, cartilage disease, and tendon injury.

Would you summarize for us the history of the Translational Medicine Institute and how it is coming into being?

We started the Orthopaedic Research Center as a one-man band, then a three-man band after Dave Frisbie and Chris Kawcak finished their Ph.D.’s. It gradually transformed from there into a pretty big program, with lots of faculty, including bioengineers, and we are already doing some translational work.

We started a dialogue with John and Leslie Malone through Dr. Mindy Story, who did the clinical work for Leslie’s dressage horses and joined our Equine Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation program. The Malones provided us with an endowed chair in equine sports medicine. At the same time, John, in particular, showed a lot of interest in stem cells, and he asked to come up and see our data – we’d never had a donor ask to see our data. We gave him an overview of clinically relevant research we’d done with regenerative therapies including stem-cell therapies in the horse, and he was very interested.

Then we presented him with the idea of, what we were calling at the time, an Institute of Biologic Translational Therapies. He pointed out straight away that it was quite a mouthful, but he was interested. We decided it was too big a mouthful, and that’s why it’s now Translational Medicine Institute. Fortunately, he said he and Leslie would be lead donors. That’s how it developed: The Malones contributed half of the building and wanted us to raise matching funds for the other half. He wanted to see other people contributing. The Malones also committed to funding $2 million a year for five years in in discretionary research dollars.

So tell us about the second really major donor who is allowing the Translational Medicine Institute to be formed, Princess Abigail Kawananakoa of Hawaii. She’s a philanthropist, a cultural leader, and a breeder of racing American Quarter Horses. How did you become acquainted with Princess Abigail? How often do you work with her and her horses, and what has been her contribution to your work here at CSU?

I’ve known Abigail for at least 30 years. She’s had a lot of success in the Quarter Horse racing business, and was an avid equestrian prior to that. Our relationship started with my operating her horses. Actually, Nancy did vet work for her before I met Abigail, so both of us have a long relationship with her.

About 10 years ago, she gave us $3 million to endow the Abigail K. Kawananakoa University Chair in Equine Musculoskeletal Integrative Therapies, so she has been a major donor, a colleague, and a good friend for a long time. We’ve kept in touch, and Nancy and I have seen her multiple times at Los Alamitos Race Course, where her horses race, near Los Angeles.

A couple years ago, I was visiting Abigail in Honolulu and told her about the institute, our plans, and the big lead gift from the Malones. We cruised up the coast of Oahu, out of Honolulu, and we saw her haunts, where she surfed as a young girl. We went to lunch, and I told her more about the proposed institute. She was really interested in it – she has always been very interested in education – and that led to her committing to fund the rest of the construction.

As part of her gift, Princess Abigail asked that Translational Medicine Institute be named in your honor. What does that mean to you?

What does it mean to me to have my name on the institute? It’s humbling. I’m honored. I certainly never imagined having my name on a building. It took a bit of getting used to, and I really appreciate how significant this is. I have to admit that I was apprehensive about what people would think, with my name being on it. But the complete support of everybody here, thinking it is appropriate, is probably more touching than actually having my name put on it. That’s really nice, and I’m very excited that we’ve got groundbreaking on the second of June and what it’s going to do for our research programs.

As we’re anticipating the construction, what are your hopes and wishes for the Orthopaedic Research Center and for the Translational Medicine Institute?

One of the things I’ve probably been asked more than anything is, “What happens to the ORC?” Well, the ORC remains the ORC. We’ve got a tremendous faculty, and it’s critical that the ORC retains its identity, continuing to focus on clinically relevant research in orthopaedics. At the same time we have colleagues in other disciplines joining us, and those people are going to strengthen us further.

What is the big arena of questioning or discovery that you hope the institute can make headway in addressing?

A big driver with the Translational Medicine Institute will be constant surveillance of commercialization potential and getting therapies into the patient. You know, there’s a lot of research done that never gets to the patient. Sometimes that’s appropriate, because there weren’t good results. TMI can function as a screener of good ideas that can help animals and humans, then we will examine ways to partner in developing those innovations and hopefully getting them to market.