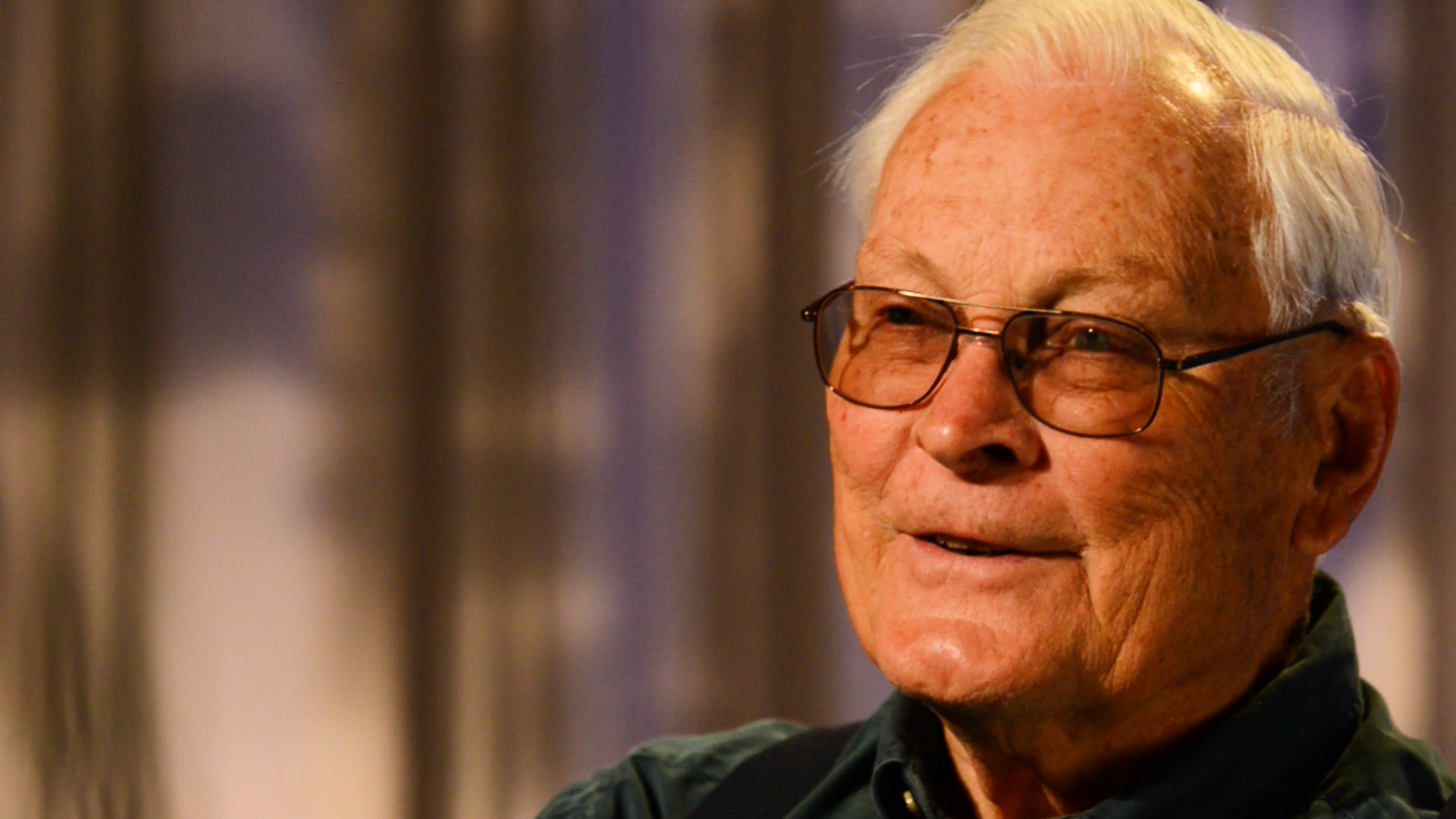

Dr. Donald L. Piermattei, D.V.M., Ph.D., was a pioneer in small animal orthopedic surgery who served as a Colorado State University professor and chief of small animal surgery at the university’s Veterinary Teaching Hospital from 1980 until his retirement in 1992.

Dr. Piermattei died peacefully of cancer at his home in Fort Collins, Colo., on Jan. 28, 2017. He was 86. He will be honored during a memorial service at 11 a.m. Feb. 11, 2017, at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, 2000 Stover St., Fort Collins. His obituary may be found here.

In November 2015, about a year before his death, Dr. Piermattei discussed his career in veterinary medicine with Coleman Cornelius, director of communications for the CSU College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

Coleman Cornelius: Please tell me a bit about when you came to Colorado State University and began doing orthopedic surgery at our Veterinary Teaching Hospital. This was 1980’s, so you would have been at the hospital off Drake Road.

Dr. Donald Piermattei: The hospital opened in the spring of ’79, and I came on board in January of 1980. So everything was bright and shiny. The attitude of everyone was just over the top, you know. Everybody was so excited about being in this new facility compared to the old one, which was extremely inadequate. So it was a really a fun place to be working at that time because everybody was enthusiastic and excited and we had just great people, you know. We had an incredible staff. We thought we were the best in the world, and we acted like it.

CC: Were you the best in the world?

DP: Well, you know, like any other thing, it depends on what metrics you apply. But I believe, at least in clinical service, both large and small animals, that we were as good as or better than anyone else at the time.

CC: Why were you attracted to orthopedics?

DP: As a kid, I made hundreds of model airplanes and wooden guns and that kind of stuff. So I was always kind of good with my hands. In veterinary school [at Michigan State University] the chief of small animal surgery was Dr. Wade Brinker, who was one of the two or three pioneers in the 1950s of modern veterinary orthopedic surgery. I graduated in the middle ’50s, so I was in the middle of all this new stuff coming out. And Wade Brinker was an outstanding surgeon and an outstanding man. I was able to spend two of the four years at Michigan State working directly with Dr. Brinker. So I got started in surgery with him and started in orthopedics under him. And I guess, just because it’s kind of a more mechanical thing than soft tissue, I was attracted to it. I could pin bones together and put bone screws in, and it was kind of like working at the workbench with tools that I was familiar with. So it seemed like a natural thing for me. Because specialization wasn’t known at that time, I was a general surgeon for 20 years. It was only my last 10 or 12 years here at CSU that I actually concentrated 100% in orthopedics.

CC: What are some of the primary differences in how veterinary medicine is practiced now compared to when you started your career?

DP: Oh, there are so many things. When I was first getting started in surgery, I would spend hours thumbing through these huge, human orthopedic instrument catalogs looking for stuff that I thought would work for veterinary patients. Contrast that to today, when there are hundreds of companies vying for your business and looking for ideas of products they could develop. It used to be that I would have to call and beg if I wanted something built special or different. We also had no technicians when I first started. We did our own anesthesia and packed our own instruments and sterilized them. Whereas today you have trained technicians, so it’s much less hands-on in one regard, in that you’re not doing the IV and putting the catheter in. This gives you some more time to concentrate on the surgery that you’re going to do. We used cloth drapes with holes sewn in them. Of course, today we have these paper-based drapes. What we call a septic technique, which is everything you do to avoid and prevent infections that you might create during surgery, all of that is 1,000 percent better than it was 50 years ago. And that’s all to the patient’s benefit.

CC: You’ve talked about how laborious veterinary care, and surgery in particular, was at the start of your career. What motivated you in veterinary medicine? What pushed you to provide this kind of care?

DP: For me, it’s always been about the patient. It’s really quite special taking care of dogs and cats. I get a little bit emotional about it because it becomes a responsibility.

CC: I wanted to ask you about your time with the U.S. Army Veterinary Corps. Where were you stationed, and what were your responsibilities?

DP: The primary responsibility was foods inspection. That involved what we called origin inspection, packing plants, canning facilities, butter factories, things like that. At the end of the Korean War, I was sent to Presidio, San Francisco, which is a beautiful place. My responsibilities were called “post-food inspection.” So I was responsible for the mess halls, sanitation, and all the food coming on the base was theoretically under my inspection control. It wasn’t terribly interesting for me at that time, and I definitely did not want to make a career of it. At the time, the enlistment period was only two years, and I enlisted as a senior, so I went in as a first lieutenant in the Veterinary Corps rather than being drafted. I earned a tremendous respect for the military that I carry to this day. I have nothing but admiration for the people who devote their lives to that.

CC: One of my favorite stories, which I would love to have you elaborate on, is that you performed surgery on one of President Gerald Ford’s golden retrievers.

DP: Well, it was an injury of the hind foot. It had become kind of a subspecialty of mine to work on the lower limbs because there was so much greyhound racing around Denver at the time, and greyhounds often developed lower-limb injuries. That case involved the bones of what we would call the instep, and the dog was brought to the clinic by one of the staff people. We examined the dog, made a diagnosis, developed a treatment plan, and then talked with Mrs. Ford over the phone with the details of the surgery. Of course, they approved it. We did the surgery, kept the dog for two or three days, and then discharged him back to the referring veterinarian for follow-up care. All my conversation with the Fords was by phone, but we volunteered to drive up to Vail to do a progress check at about two weeks post-surgery. My wife, the surgery tech, and I drove to Vail on Sunday afternoon and examined the dog and met Mrs. and President Ford briefly at their condo. The dog, fortunately, was doing well and made a good recovery.

CC: One of the lasting marks you’ve had on veterinary medicine is authoring two seminal textbooks, “An Atlas of Surgical Approaches to the Bones and Joints of the Dog and Cat” and “Handbook of Small Animal Orthopedics and Fracture Repair.” How did you start writing these books, and what did you want to achieve?

DP: The first one, the Atlas, is a sort of a surgical anatomy book showing how to make an approach to the bones and joints for accomplishing some type of repair or fracture repair or joint stabilization.

At the time, there was only one surgical text for small animal surgery that was modern. In 1964, I was on the staff at Texas A&M in the small animal surgery section, and I was wandering through the veterinary library one day. My eye was caught by a book, a human book of surgical approaches to the bones and joints. I looked at it and I thought, “You know what? We could do this. This would be really useful.” I knew a fellow in the anatomy section, Gordon Greeley, who was an amateur artist and who drew visual aids for the anatomy department. I approached him about this, and he was interested. I had really good lights and a 35 mm camera that I taught myself how to use. We started dissecting cadavers, and I would do the procedure, and we would photograph it in steps, and Gordon would take notes and do sketches. We did the thing in various steps, of course, anywhere from three to four or five panels for each procedure.

We sent a blind proposal to W.B. Saunders publisher. They accepted our proposal for the book, and we spent about a year getting it ready. It was my first experience writing anything other than my master’s thesis. I did most of it between 4:30 and 6 in the morning. We got it published in 1965. It’s 50 years old now. It’s in its fifth edition. I transferred authorship of the last edition to a former resident of mine who is now in Australia, and he put up the fifth edition.

But the thing about that book is, nobody has ever tried to duplicate it. Of hundreds of texts that are now available in veterinary medicine, there’s only one for this. And that’s a source of real satisfaction. Because it is unique, a lot of veterinarians have it, and a lot of students are exposed to it. You can go almost any place in the world in a small animal practice and find it on a bookshelf. That’s been a great source of satisfaction, to think that we’ve had a positive influence on so many veterinarians and so many patients.

CC: You have called yourself a modifier of techniques in orthopedic surgery. What does that mean?

DP: Well, I never had any huge breakthroughs, you know, a revolutionary new approach to a problem. In the course of doing the surgical approaches I was able to develop a few things that to my knowledge had never been published before. So those were innovative. Surgical technique-wise, I think that I just modified and improved a lot of other people’s original work. I can’t claim credit for the originality. I just had my own way of doing things, and in a lot of cases that worked out well.

CC: But, ironically, one of your innovations was in soft tissue surgery.

DP: Where did you get that from? [Laughter] Yes, I just stumbled onto a technique to get stones out of the urethra of male dogs. Stones in the urethra are a problem. You’ve either got to flush them back into the bladder or through the urethra. I developed a technique to wash the stone back into the bladder, where you can then retrieve it. I never thought anything of it. When I got to the University of Minnesota, one of the staff people was very interested in urinary tract problems. I was just working on a patient one day, and I did this in front of him, and his eyes just blew out, bulged out. He said, “That’s so cool. Where did you publish that?” I said, “Oh, I never published it.” He said, “Oh, you’ve got to,” so it got published.

CC: I wonder about your motivation to have an impact on individual students. Would you elaborate on what that means to you?

DP: Teaching veterinary students, you’re working on basic skill sets. But when you have a resident, these are people who are at least one year out of veterinary school. They’ve gone through an internship before they start their residency program, which is three years with progressively increasing responsibility and freedom. Your objective is to send those people out at the end of the third year better than you are. If they’re not, you really haven’t done your job. That way, everybody coming after you is really in many ways better than you are, which doesn’t deprecate you – it shows how much we’ve progressed. It’s a great pleasure to send them out and see them succeed.

CC: In 2009, you received the American College of Veterinary Surgeons Founders Award for career achievement. Share, if you would, what that meant to you.

DP: Well, it was huge because I was pretty closely involved with the founding of the College of Veterinary Surgeons, which is the group that certifies people as specialists in both large and small animal surgery. It was a group that I devoted a lot of time and energy to, particularly in the earlier years when there were only 50 or 75 of us. So to be recognized by this peer group was really special.

CC: One of my favorite facts about your life is that for many decades you were an airplane pilot and built three airplanes. What are the similarities between piloting and veterinary medicine or surgery?

DP: None that I know of! My interest in aviation predated my interest in veterinary medicine. From the time I was in kindergarten, I was fascinated with airplanes. No idea why, but I was making airplanes out of orange crates and drawing pictures of airplanes. I thought I would go into some aspect of aviation, and I was thinking about aeronautical engineering. But when I got out of high school in 1948, there were enough aeronautical engineers and pilots left over from World War II. I had this interest in horses, and it really just came to me out of the blue when I was a senior in high school. I thought about human medicine and was afraid I didn’t have the people skills to do that. It just came as a bolt out of the blue, “Well, dummy, veterinary medicine is the place you ought to be.”

It helps to be detail-oriented. Staying organized when you’re flying is important. You have to do a lot of things simultaneously, and you have to establish priorities. You know, keep the airplane right side up, to begin with, before you talk to the guy on the radio. All that has probably developed the mindset that you follow in surgery – thinking ahead and thinking what your next move is, what next instrument you’re going to need. I never considered myself to be a fast surgeon, as far as how fast my hands worked, but I was fast in the time that it took to do a surgery. So I attribute that to being organized and keeping it flowing.

CC: So there are similarities.

DP: I hadn’t ever really thought of it in that way [Laughter].

CC: What are the most significant developments you’ve seen in teaching veterinary medicine?

DP: Probably the further development of the specialties has changed the way that students are taught to some degree. That’s been a big change – and getting away from the classical lecture that I was used to. The core mission is the same, but the way to get there has changed a lot. The fun thing remains that you’re working on such neat patients.

CC: And as you look over your career, what do you feel most proud about?

DP: Well, again, it’s the patients. I think a lot of dogs and cats have led a lot more active, comfortable, pain-free lives because of what I’ve done personally and what other people have done that I helped educate.

CC: Thank you so much for sharing your insights.

DP: My pleasure.