Some astronomical cells have arrived on campus.

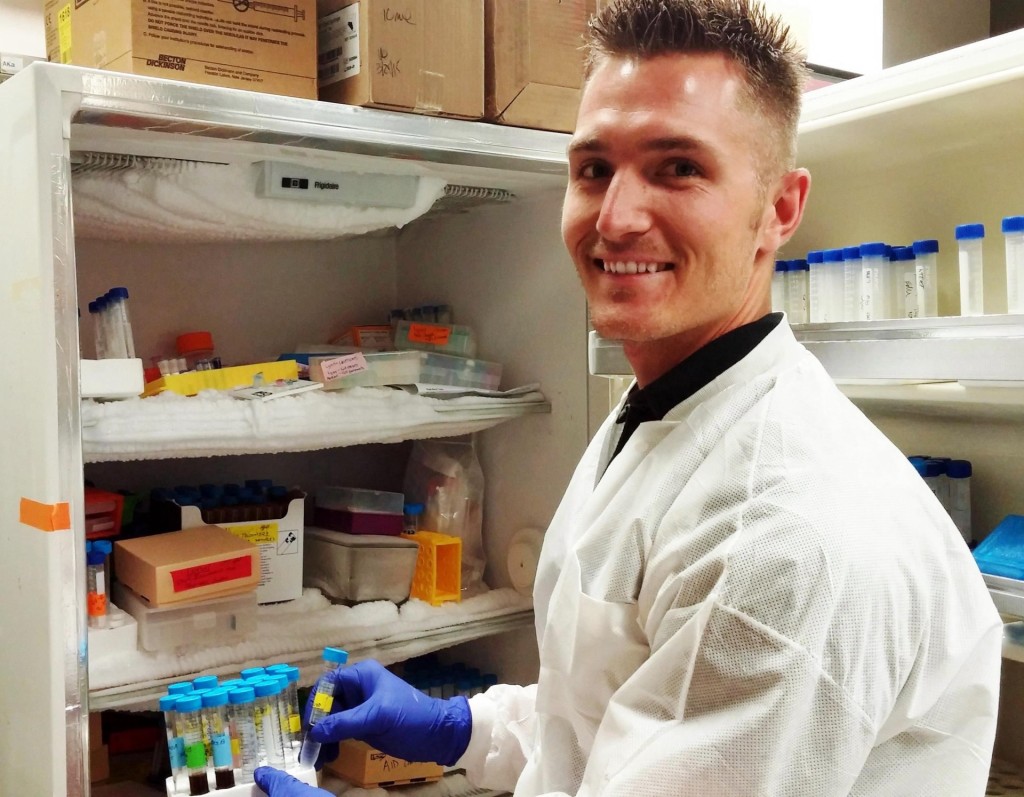

The first cell samples from astronaut Scott Kelly – who is orbiting Earth with a crew on the International Space Station – are now undergoing analysis in the laboratory of Colorado State University researcher Susan Bailey.

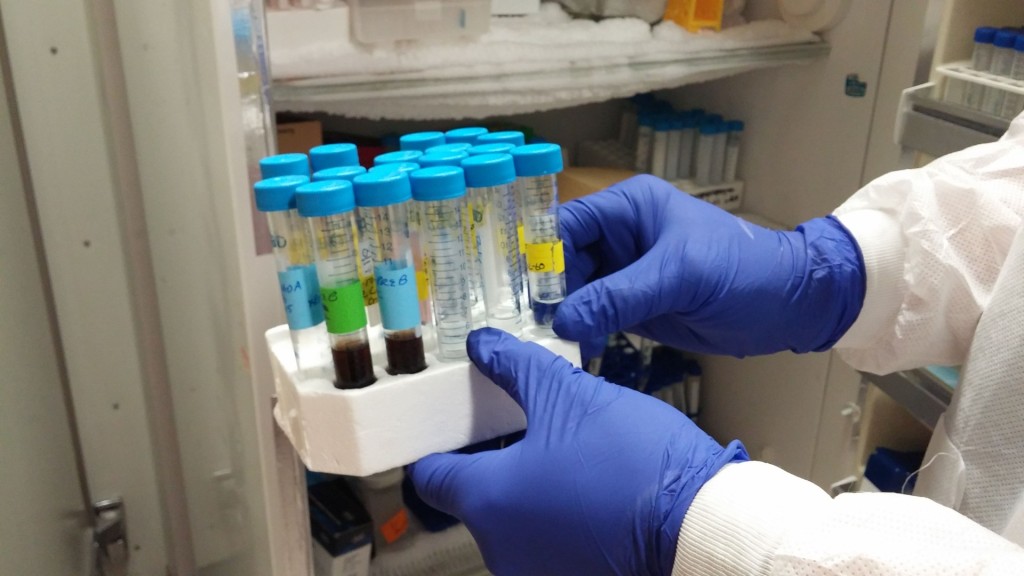

Like fresh-picked produce bound for market, the biological shipment jetted from space to its first lab stop in a mere 36 hours. The sequence: blood draw from Kelly on the Space Station, transport by Soyuz spacecraft to Kazakhstan along with returning Russian astronauts, then on to a laboratory at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston for processing and final shipment to Fort Collins.

“Isn’t that something?” Bailey, a professor in the Department of Environmental and Radiological Health Sciences, enthused shortly after receiving the sample this week. “When you think of the journey it went on, that’s pretty remarkable.”

A study out of this world

Here, Bailey and her graduate students are analyzing Kelly’s cells to help determine effects on the human body of extended space travel, which is need-to-know information as NASA prepares for an eventual human mission to Mars. Such a mission would require space travel for more than a year, subjecting astronauts to intense space radiation.

Bailey is working as part of the highly publicized study of identical astronaut twins Scott and Mark Kelly, which uses earthbound Mark’s bodily samples as a comparative basis to determine what happens to Scott during a full year in space. Bailey, one of 10 primary investigators involved in the research, is focused on radiation-sparked cellular changes that could indicate risk for cancer.

For years, CSU faculty members have attracted NASA funding to study cancer risks associated with space radiation.

“From a scientific standpoint, it would be neat to see a change. But from a personal standpoint, I’d like to see no change at all because that would indicate stability in the health of astronauts,” said Miles McKenna, a doctoral student in Bailey’s lab who is conducting much of the cellular analysis.

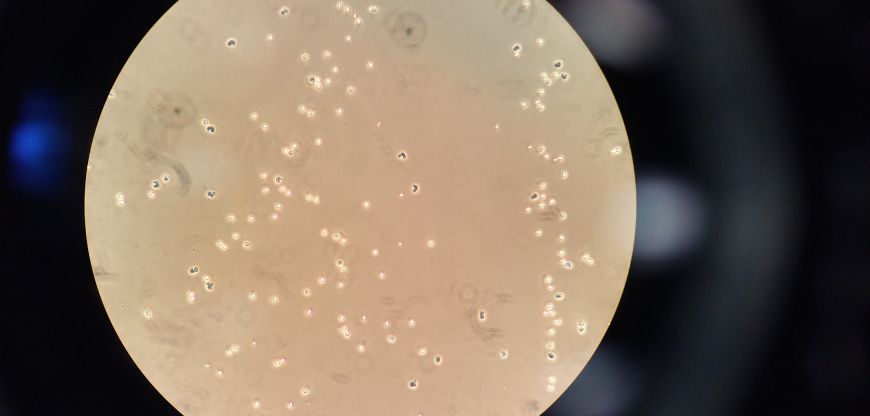

Bailey and her graduate students are specifically watching for changes in telomeres. Like plastic coating at the ends of shoelaces, telomeres cap the ends of chromosomes, protecting against degradation of the genetic code.

As people age, the protective caps break down; telomerase activity changes and telomeres shorten. Stress of all kinds and environmental exposures, including radiation, also contribute to telomere shortening, Bailey said. These cellular changes affect the pace of aging and may heighten the likelihood of developing a number of diseases, including cancer.

The first study of its kind

This is the first study to evaluate these biomarkers of aging and how they are affected by space flight.

McKenna, pursuing a Ph.D. in cell and molecular biology, has already traveled to Houston to confer over data with fellow scientists.

“Everybody is interested in this project, especially with conversation about one day going to Mars,” McKenna said. “It’s an amazing experience, and I’m pretty thrilled to participate.”

To hear an interview with Bailey on Colorado Public Radio, visit the Colorado Public Radio website.