Professor Kurt Fausch’s constantly evolving career is marked by groundbreaking contributions to stream ecology, a passionate dedication to mentorship and teaching, and recently, a drive to engage the public to conserve rivers.

Fausch recently received the American Fisheries Society Award of Excellence, the organization’s highest award. It has been awarded annually since 1969 to recognize outstanding lifetime contributions in the fields of fisheries science and aquatic ecology.

“Over Dr. Fausch’s career, he has been a consummate professor in all areas,” said Ken Wilson, head of the Colorado State University Fish, Wildlife and Conservation Biology Department where Fausch has been a faculty member since 1983. “One word — excellence — truly captures the essence that is Kurt.”

Since coming to CSU, Fausch has steadily built a wide-ranging program in stream ecology and the impacts of humans on rivers. His contributions have changed the ways land managers and researchers think about fish life cycles and the role of rivers in the broader ecosystem.

“He’s always been passionate about good science and cares deeply about making a difference on the ground,” said Jason Dunham, supervisory research ecologist with the U.S. Geologic Survey. “His work pulled us out of an angler-centric view of trout and fish ecology and to more of a landscape ecological view.”

Major breakthrough

Fausch’s first major breakthrough came by challenging a dominant paradigm about the scale at which fish live their lives in rivers and streams.

“Rivers are branched similar to trees,” explained Fausch. “Fish need access to various parts of that tree for different parts of their life cycles, but at the time, researchers and managers were only looking at small areas and assuming that fish lived their entire lives there.”

The “riverscape” idea meant considering the various habitats throughout much longer segments of the stream and whether infrastructure was preventing fish from accessing areas they may need to spawn, find food, or overwinter.

“We put so many barriers in streams,” Fausch said. “But, fish aren’t like birds who can fly around or over them. It would be like telling someone that all the routes to their only grocery store are closed. Good luck finding food.”

As this idea has taken hold, stream management and research has changed significantly. For example, replacing culverts that are barriers to fish movement to avoid trapping fish downstream is more commonplace, and research has shifted to consider whole watersheds and employ methods to study longer reaches throughout rivers.

“Kurt’s contributions to the spatial scale we need to consider brought to light ecological concepts and understanding of how fish behavior works at multiple scales,” said Associate Professor Amanda Rosenberger of the University of Missouri Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit.

‘River webs’

Fausch’s next contribution was to help link terrestrial and aquatic ecology by showing how rivers affect the forests and grasslands they flow through, and vice versa. Others coined the idea of “river webs.”

Working with Japanese ecologist Shigeru Nakano, Fausch showed that the insects coming out of streams, support animals in the broad habitat well beyond the river, and that insects and other invertebrates falling into streams support fish.

“The first law of ecology is that everything is connected,” said Fausch. “With the river webs idea, we and other researchers have shown how energy coming into the river from insects falling in supports fish, and that insects leaving the river support birds, bats, lizards, and spiders.”

Fausch introduced Nakano to using large-scale field experiments in Japan, which were used to verify these ideas. In one case a tent placed over a long reach of the stream prevented insects from falling in or leaving and the lack of prey led to the departure of bats from the area.

Their discoveries created a sea change in ecology, whereby researchers and managers began integrating the aquatic and terrestrial parts of a system. “He pulled fish and other river organisms into the food web,” said Dunham “As an applied ecologist working on river systems, and not a ‘trout-guy’, it was awesome to see others ahead of me in their careers like Kurt with these kinds of ideas.”

Beyond academics

These scientific contributions are enough to place Fausch among preeminent ecologists, but late in his career Fausch also began reaching beyond academics to the public to encourage river conservation.

Described as an “incredible journey” and “remarkable transformation” by his colleagues, Fausch now uses the power of personal stories to reach non-scientific audiences.

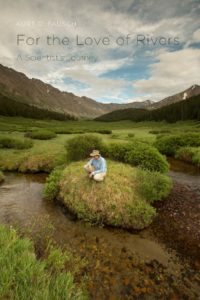

He is the executive producer of the film River Webs: A True Story about Life, Death, Science and Streams, and the author of the award-winning book, For the Love of Rivers.

River Webs tells the story of Fausch’s work with Nakano, whose untimely death affected Fausch deeply. The film, beamed into more than 100 million homes via PBS affiliates, brought the river webs concept to lay audiences.

“Flying back from Japan in 2009 it struck me, if 1 percent of those people watched the film, that’s a million people,” Fausch recalled, pointing out that is far more than would ever read his academic works.

The success of River Webs inspired Fausch to write For the Love of Rivers as a memoir and call to action for the public to become more invested in the protection of rivers. The book won the 2016 Sigurd F. Olson Nature Writing Award.

Out of the comfort zone

For a career academic, these endeavors pushed Fausch out of his comfort zone, something he encourages other academics to do as well. “The death knell is to keep doing the same things, year in and year out,” he explained.

Fausch has not only learned something different, but he’s also excelled at it.

“He’s had the courage to change late in his career from science to creative writing.” Dunham said. “That’s a big, humbling, transition, to learn something completely different.”

But “humble” is a word consistently on the tip colleagues’ tongues when describing Fausch. “Kurt is kind, generous with his time and ideas, and always happy to be a mentor,” said Rosenberger.

“While he is scientifically critical and says what’s on his mind, he’s very collegial and well mannered all the same,” said Dunham. “He’s never confused freedom of thought with freedom from responsibility.”

Fausch plans to retire following the Fall 2016 semester and is looking forward to teaching his favorite classes one last time.

“I’m happy students are still excited to take my courses,” he said. “Teaching is a chemistry between you and the students, and if you can’t generate enthusiasm in the class then you should do something different. I’ve always loved inspiring students through teaching.”

Describing teaching and mentoring graduate students as a calling rather than a job, Fausch can certainly look back on his legacy of impacts on students, land managers, researchers and the public as one that made a significant, lasting, difference in the world.