Earth, you never looked so good

by Anne Manning | April 5, 2017 2:15 PM

Earlier this year, the U.S. agency in charge of atmosphere, climate and ocean, NOAA, unveiled the first images taken by its latest, greatest weather satellite, GOES-16.[1]

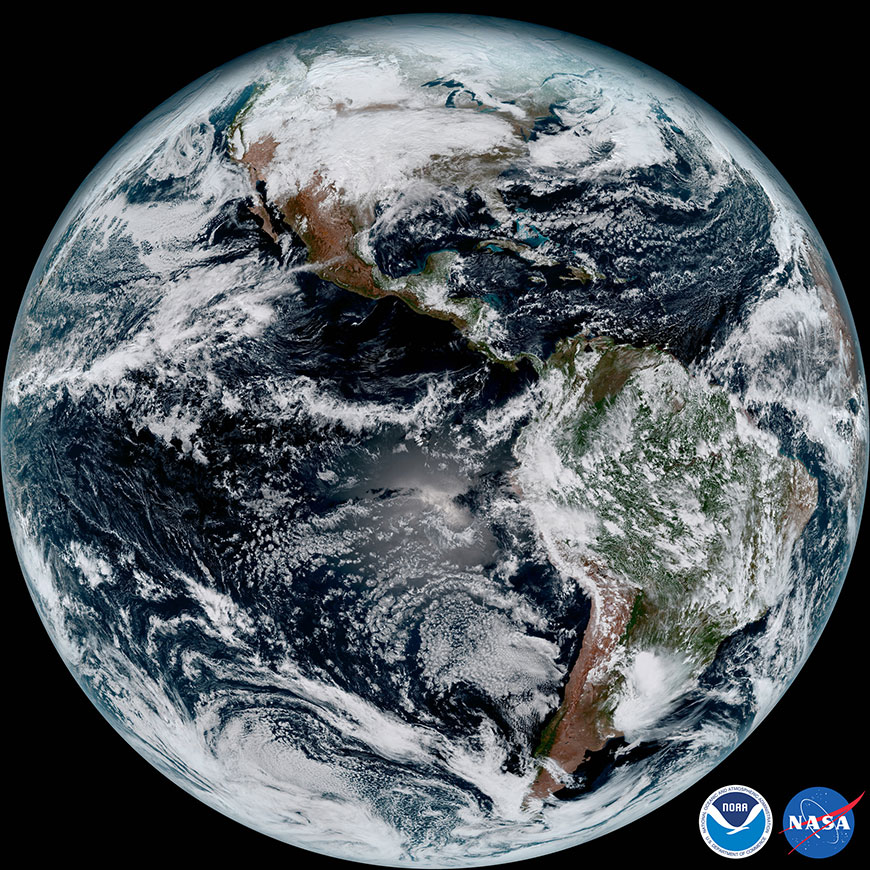

A full-disk, true-color image of Earth taken by GOES-16. Credit: NOAA/NESDIS

The sharp, full-color images of our Blue Marble signal a new era of weather mapping and forecasting. Many of those images were processed at Colorado State University by a team dedicated to making GOES-16’s new capabilities accessible to all.

NOAA research scientist Dan Lindsey co-leads a CSU-based team that interprets data from GOES-16’s main camera, the Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI).[2] The team’s task is turning terabytes of ABI data into high-resolution pictures of things like hurricanes, wildfires and dust storms as they’re happening – images that could potentially save lives by, for example, triggering early evacuations during severe weather. Anyone from the National Weather Service to the general public will eventually be able to use the team’s images.

The satellite, which launched into orbit in November 2016, is new enough that the government still considers all its data preliminary; GOES-16 should be declared fully operational, and parked in its permanent orbit, later this year.

GOES-16 scientists are busy validating this preliminary data, while creating stunning images that illustrate the new satellite’s advanced capabilities.

“Our job is to take the 1s and 0s coming in and figure out what to do with them to make the data useful for forecasters,” Lindsey said.

Lindsey, who earned his M.S. and Ph.D. in atmospheric science at CSU, works at CSU’s Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere (CIRA). Established at CSU in 1980, CIRA is one of 16 national institutes that embed government weather and satellite operators at research universities. He leads the local ABI team of about 20 with Steven Miller, a CIRA research scientist and also a CSU alumnus.

Better, faster, more colors

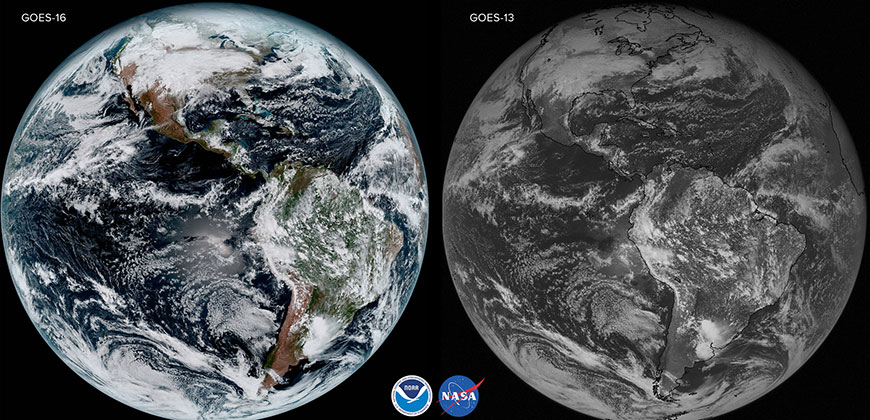

The ABI is one of GOES-16’s signature technologies (others include a lightning mapper and a set of instruments to monitor space weather). Like a constantly clicking camera, the ABI documents weather patterns on Earth using 16 spectral bands, compared with just five spectral bands on still-operational predecessor satellites GOES 13 and GOES 15. This panorama of wavelength channels includes two visible channels – reflected sunlight from the Earth – four near-infrared, and 10 infrared. That amounts to three times the spectral information, four times the spatial resolution, and five times faster coverage than previously possible.

In other words: we’ve gone high-def, after years of standard-def television.

A comparative image of Earth taken by GOES-16 and GOES-13, its predecessor satellite. Credit: NOAA/NESDIS

Thanks to scientists like Lindsey and Miller, the ABI gives us what are called true-color images – the blue oceans, brown deserts and green forests that the human eye naturally perceives. This ability to see things as they are will give us a clear and intuitive new view of weather and climate events.

Algorithms for true-color imaging is Miller’s specialty. Last year he co-authored a paper titled “A Sight for Sore Eyes[3]” that describes the original 1960s innovations of true-color satellite imagery, and how the technology has improved.

“True-color images are not just beautiful; they are also going to give forecasters an edge for assessing any developing weather event,” Miller said.

When GOES-16 headed to space on Nov. 19, 2016, scientists like Lindsey and Miller had had a lot of practice producing such images. They were part of the GOES-16 “proving ground,” for proving the concept of the ABI’s (and other instruments’) newer capabilities. The key was access to similar data from a Japanese satellite called Himawari-8. That satellite carries a near-identical instrument to the ABI, and the Japan Meteorological Agency shared Himawari data with its U.S. counterparts.

Weather movies are the best movies

The G in GOES stands for “geostationary,” which means the satellite stays at a constant altitude of about 22,000 miles and follows Earth as it turns. Thus, GOES-16 is always staring at roughly the same place at the same time, allowing it to make movies, not just take one snapshot and move on.

What’s more, the ABI can take a full-disk image of Earth – a wide shot of the entire planet – every 15 minutes; previous satellites could only send back an image every three hours.

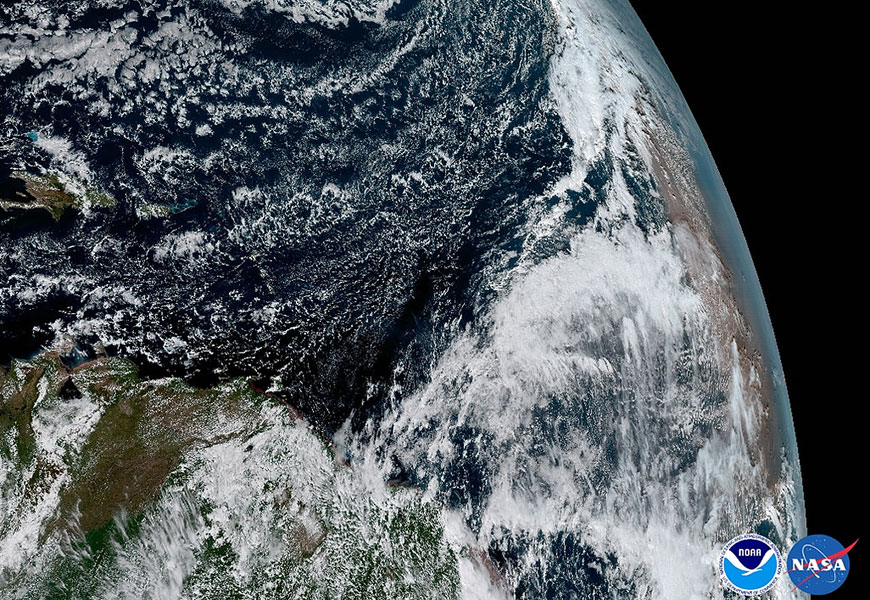

Saharan dust is visible to the right. Dry air can affect tropical cyclone formation; images like this will give forecasters new insight into storm intensification. Credit: NOAA/NESDIS

So what does all this mean for Lindsey, Miller and the rest of the ABI team? They can produce Earth images with unprecedented detail and clarity. They can watch a tropical cyclone as it spins, and take photos of gravity waves emanating from the storm’s center. They can see dust as it moves across the Sahara Desert. They can show distinct shades reflected by clouds and smoke during a raging forest fire. None of this was possible with predecessor GOES satellites.

CIRA leadership and members of the GOES-16 and ABI teams celebrated the new satellite during a March 28 ceremony on campus. They presented CSU President Tony Frank, Vice President for Research Alan Rudolph, and Dean of the Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering David McLean with framed “first light” GOES-16 images – which represent just a small taste of what’s to come.

Research scientists Steve Miller and Dan Lindsey, and CIRA Director Christian Kummerow, present President Tony Frank with GOES-16 first light imagery, March 28.

- GOES-16.: https://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/GOES-16

- Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI).: http://www.goes-r.gov/spacesegment/abi.html

- A Sight for Sore Eyes: http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/10.1175/BAMS-D-15-00154.1

Source URL: https://source.colostate.edu/earth-never-looked-good/

Copyright ©2024 SOURCE unless otherwise noted.