To produce groundbreaking research results, you often need access to new technologies and systems that can get you to the next level.

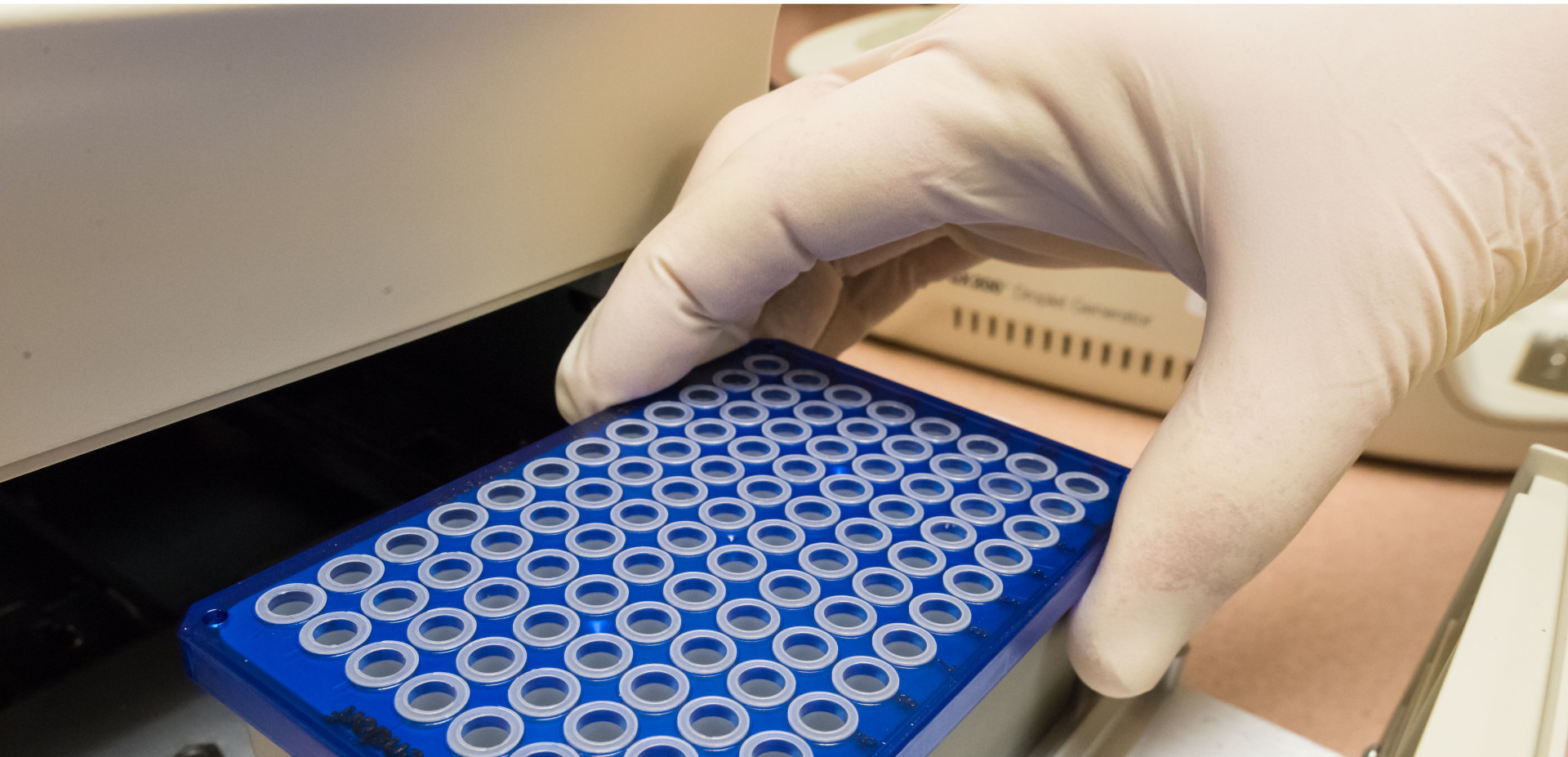

Carol Wilusz, associate professor in the Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Pathology, understands this concept, and she worked recently with Colorado State University’s Office of the Vice President for Research to bring what’s known as a digital PCR system to campus. The system provides an incredibly sensitive analysis of DNA samples, which is critical to a wide range of fields in the life sciences.

PCR — which has been described as a DNA copying machine — stands for polymerase chain reaction, a technology created by chemist Kary Mullis. The development of this technology was a huge breakthrough; Mullis received a Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1993 for creating it.

“It was ground-breaking back then,” said Wilusz, who serves as director of the Molecular Quantification Core. Shortly after she arrived at CSU in 2003, she acquired a real-time PCR machine for use in her research; the digital version is “the next big jump,” she said.

One sample, transformed by 20K

The digital system, amazingly, splits one small sample into 20,000 droplets; it’s akin to conducting 20,000 experiments in one small tube.

Wilusz said the price tag for this new system was $129,000, which made it almost impossible for a lab to purchase the equipment on its own. “That’s a big chunk of money,” she said. “But I felt that there would be enough people interested in trying it to make it work.”

And there was.

Wilusz brought the digital technology to campus with financial help from the Emerging Innovations Fund in CSU’s Office of the Vice President for Research. Her department also helped out, and she secured contributions from the Department of Environmental & Radiological Health Sciences, the Institute for Genome Architecture and Function, and the College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences.

System available across campus

Thanks to these additional contributions, some parts of the system have been duplicated and placed in several buildings — Microbiology, Molecular and Radiological Biology, Pathology, and the Research Innovation Center — to improve access across campus.

What are the advantages? Wilusz said the results are easier to understand, compared with the real-time PCR — researchers get a number, instead of having to use complicated software to calculate findings — and it’s also easier to train people on how to use the system.

“It takes me two to three weeks to teach students on the real-time system, and I could teach them now in one lecture,” she said.

John Anderson, lab manager, said that he has trained more than 50 CSU researchers to use the new technology since last November. The digital PCR system has also analyzed more than 800 samples for 11 scientists in January 2016 alone.

Anderson said that the digital PCR system works well for researchers with a limited supply of a sample, whether it is blood or other substances, and those trying to detect a very small amount of DNA.

“It’s also a lot more accurate,” he said. “With real-time PCR, you could see a 10 to 20 percent error. With this machine, you might see a 1 or 2 percent error.”

The new system can also be more cost-effective and can save time.

Researchers enthusiastic about digital PCR system

CSU researchers studying mosquito viruses are already benefiting from this new technology. “Usually, they would have to take 20 mosquitos and analyze them, but with this machine, you can look at the blood meal in a single mosquito,” Anderson said. A blood meal is the protein needed by female mosquitoes so that they can reproduce.

Todd Gaines, assistant professor in the Department of Bioagricultural Sciences & Pest Management, said the new PCR system allows him to measure gene copy numbers in plants more accurately than ever before.

“We’re now able to study the evolution of herbicide resistance in new and exciting ways,” Gaines said. “We’ve found that plants can evolve changes in gene copy number for herbicide resistance, just as they do for disease resistance and abiotic stress, which is the negative impact of things like intense sunlight.”

Researchers in the Akkina Lab studying vaccination and antiviral therapy for HIV are equally enthusiastic. “So far, I was able to accurately quantify viral RNA copies in HIV-2 and its predecessor, SIVsmm, and discriminate one from the other,” said Dipu Mohan Kumar, MIP post-doctoral researcher.

Owen Richmond, also a post-doctoral fellow in the Akkina Lab, said he’d previously had trouble detecting what he was looking for with other PCR systems.

“Because HIV2 inherently replicates at much lower levels than HIV1, detecting the presence of both viruses can be difficult,” he said. “The digital droplet PCR divides the reaction into several thousand individual reactions, which allows for detection of a small amount of HIV2, even in the presence of a large amount of HIV1.”

The core currently charges 75 cents per sample for researchers to use the machine. This cost will soon increase to support regular maintenance of the system.

The Emerging Innovations fund has also backed efforts to purchase flow cytometry technology and an experimental pathology core.

Contact Wilusz or Anderson for training on the digital PCR system.