Winning grants for mosquito research is just as competitive as “Dancing with the Stars.” Rushika Perera should know. The assistant professor of virology recently won a 2016 Boettcher Foundation Webb-Waring Biomedical Research Award, one of 10 in Colorado, for her studies of mosquito-borne viruses at Colorado State University.

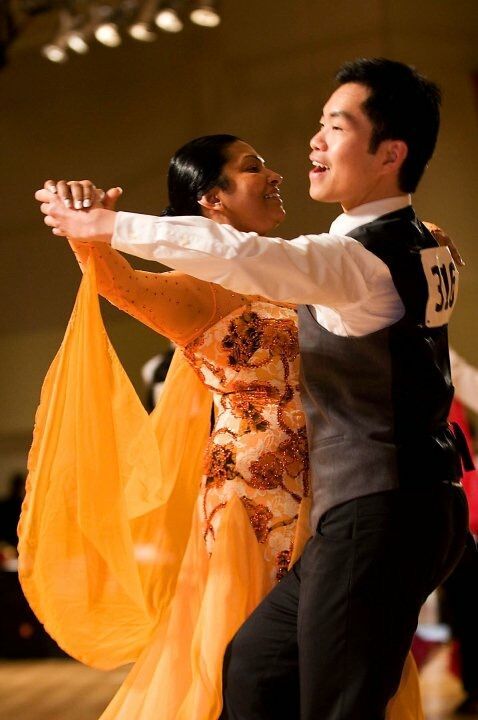

When she’s not in the lab, she’s on a dance floor, competing in ballroom, Latin and West Coast Swing dance events around the country. She actually wrote the Boettcher grant application at a dance competition. “I was energized. I just sat and wrote for 12 hours, all through the night.”

Perera knows the value of good mentoring, whether it’s waltzing with her coach Artem Chigvintsev, of “Dancing with the Stars” fame, or teaming with National Academy of Sciences fellow Barry Beaty in CSU’s Arthropod-borne and Infectious Diseases Laboratory. Beaty, a CSU Distinguished Professor who has mentored Perera in her investigations of dengue virus, calls her a “true team player, hardworking and self-starting.”

Perera grew up in Sri Lanka, the child of two doctors. But when it was time for her to attend college in the early 1990’s, civil war had made her homeland too dangerous, so she lobbied her parents to allow her to apply to colleges in the United States.

“My parents said, ‘Do you want a dowry or an education?’ And I said, ‘Education, of course.’ But it was life-threatening to go to the university there,” Perera said. “Coming abroad was difficult, too. Basically we bought my ticket by selling the piano and other family heirlooms.”

The dowry covered her first year of undergraduate tuition, and Perera served food in the cafeteria and cleaned bathrooms, in addition to working as a lab assistant, to put herself through school. She earned bachelor’s degrees in chemistry and biology at Goshen College in Indiana, and went on to earn a Ph.D. in biological sciences from Purdue University.

“I knew I did not want to do medicine. I was more excited about figuring out the details of how things work,” Perera said. She explored plant biology, genetics, yeast biology and cancer research through internships before discovering a fascination with viruses that sustained her doctoral and post-doc work at Purdue and the University of California, Irvine.

Anthony James, a Distinguished Professor in the UC Irvine School of Medicine and School of Biological Sciences, calls her “a scientist of exceptional promise.” The prominent molecular biologist who has called mosquitoes “arguably the most dangerous animals in the world,” nominated Perera for the Boettcher award. “She has displayed courage and acumen in taking on this major endeavor, one which could have significant impact on human health,” James wrote.

Mosquito-borne viruses: a quadruple threat

For the past three years, Perera has run a lab on CSU’s Foothills Campus, studying how dengue, chikungunya, yellow fever, and Zika viruses behave in their mosquito hosts, specifically, in the midgut. That’s where the action is, virus- and blood-wise.

“The midgut is like the stomach of mosquito, when the mosquito takes a blood meal, it goes there. The virus is acquired in the blood and that’s where the replication starts,” explained Perera, who has a knack for making her cutting-edge research intelligible.

It’s that articulate combination of innovative science and straight talk that won her the $225,000 Boettcher grant, which will fund three more years of investigation into mosquito-borne viruses that threaten to infect more than 3 billion people in over 100 countries.

As mosquitoes become resistant to insecticides, researchers are looking for new ways to block disease transmission. Perera studies metabolomics approaches to identify molecular “choke-points” that can be exploited to eventually block mosquito-human viral transmission.

With the rise of the Zika virus, one might think we already know plenty about mosquitoes, given the number of devastating mosquito-borne viruses – including Zika – that strike people and animals around in the world.

“We do, but we don’t, and that was the premise of my Boettcher grant. All this time, we’ve been focusing on insecticide control, so just spray the hell out of the mosquitoes, but a lot of these mosquitoes are becoming resistant,” she said.

Seeking a new way to stop disease

Perera’s premise: If other methods of control are not working, why not try to prevent the infected mosquito from spreading the virus?

“My research focus is what kind of biochemical changes are happening in the midgut that allow the virus to replicate, and can I control or block that?” She thinks the answer is yes, but like a dance routine, there are numerous intricate steps involved.

“Technically, it’s very challenging. My last experiment used 6,000 mosquitoes, and we have to get females, so it’s half each time, and only half of those may get infected in the laboratory. They like feeding on your skin — they don’t like feeding through a plastic membrane.”

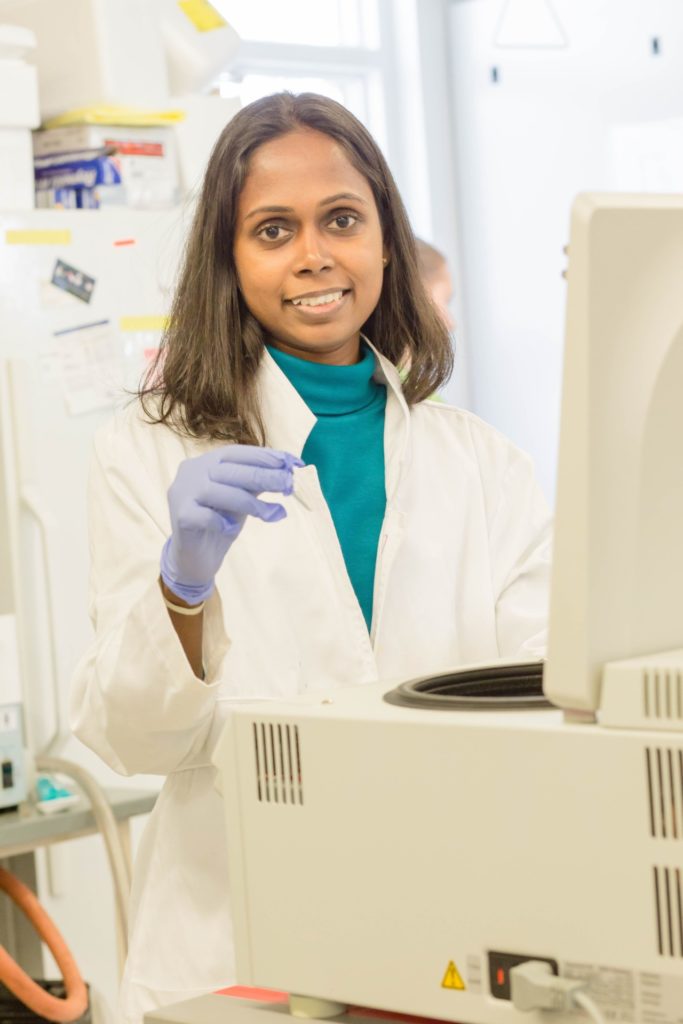

Once the mosquitoes are fed and infected, Perera’s lab dissects the tiny creatures to look at their guts. Mass spectrometry makes it possible to measure and identify the molecules within.

“You have to dissect a bunch of midguts because they are very tiny tissues. Then you send it for mass-spectrometry, and that’s the expensive part. Then you spend months evaluating the results. It’s a lot of work but what comes out of it is really exciting information. It’s a tremendous technical feat.”

She expects her findings to inform methods to prevent the spread of malaria, West Nile virus, Zika, and other important pathogens that are transmitted by mosquitoes and other insects.

[masterslider id=”168″]

Her turn to lead

Perera is now at the point in her career when she takes the lead with younger researchers, recommending them for fellowships and providing guidance in and out of the lab.

Nunya Chotiwan, a Ph.D. candidate from Thailand and CSU nominee for a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Student Research Fellowship, has worked in Perera’s lab for three years, studying dengue virus and mosquito metabolites. “She is a very good mentor. She spends a lot of time with each student, driving the project forward, both the concept and the technical parts. In the lab, she listens to us.”

Outside the lab, the students and their mentor socialize at dance meet-ups in Fort Collins. “I hang out with her quite a lot. She got me into West Coast Swing. We dance to get rid of stress,” Chotiwan said.

After more than 25 years of dancing and academia, Perera sees herself stepping into in new, but related, roles in the lab and the dance studio. “Dance allows me to impact people’s lives through teaching and encouragement. I have realized that my years of dance has provided me with an opportunity to touch people’s lives,” she said.

Although he hasn’t seen her dancing in the halls of the Arthropod-Borne and Infectious Diseases Laboratory, director Greg Ebel understands a scientist’s need for a creative outlet.

“Science is a hard job. You get rejected and fail a lot. It takes a lot of training, and it can be fairly lonely. So, to have something outside the lab is really important,” Ebel said. “Many accomplished scientists I know have hobbies in the arts, although we’re not world-class ballroom dancers.”

When Sri Lankan graduate student Sachini Fernando first arrived in Fort Collins to study Aedes aegypti mosquitoes with CSU professor William Black, she was thrilled to meet a fellow Sinhalese speaker in Perera, who has mentored her in lab and life techniques.

“She said ‘I’m dancing, so you can come with me,’ and now I kind of like it. I’m inspired by the amount of work she does in the lab and still finds time to socialize and dance,” said Fernando. “I’m really grateful to her for the support, and I am interested in working with her in the future, and having a collaboration in Sri Lanka with her ideas.”

Perera will return to her homeland this summer with dual goals: to assist in mosquito research there, and to “find a path to bring students here, train them and send them back, so that research in Sri Lanka can progress as well. Dengue is huge in Sri Lanka, there are kids dying from dengue all the time.”

A bridge to future research

The Boettcher grant is designed to bridge researchers’ funding from the university “starter package” to the intense competition for federal dollars.

“Funding for the biomedical sciences in the U.S. is difficult right now, and one of the areas that’s really a problem is getting talented young scientists off the ground. Rushika was at the end of her startup phase, so this award is huge,” said Ebel, who appreciates her energy and creativity around the lab.

“It’s a reality,” Perera said. “There’s significant competition in the scientific community and you just have to push through it. As a junior investigator, it’s difficult for me to invade that space. Now I can actually do the work and be recognized for the work, and the big shots will start talking to me.”

She is undaunted, calling on years of struggle to sustain her.

“Nothing was easy for me to get here, but it’s like a dream come true already because I’m here. This place is like heaven. I couldn’t have asked for a better position because CSU has everything I would ever need for my research. I just feel like I can do wonders here,” Perera said.

“You have to look for new avenues for controlling these diseases. These new avenues are new because they’re difficult. I think it will be a completely uphill battle, but the good thing about the Boettcher is that it lets you take a risk – and that’s a huge gift to me. Also, I get a lab coat with my name embroidered on it. I’m very excited about this.”