A Colorado State University faculty member and his students have been getting out of the classroom and into a community that has seen its share of struggles in recent years — but a greater number of victories.

It’s a community that is one of the most diverse in the state, but it’s not a Denver suburb. It’s the small, rural town of Fort Morgan on the eastern plains. And it’s served as an opportunity for students in CSU’s Department of Ethnic Studies to witness — and participate in — evolving real-world race relations.

Eric Ishiwata, a CSU associate professor of ethnic studies, came to the Fort Morgan project by way of Japan.

His previous research focused on the recruitment of Brazilians of Japanese ancestry to be unskilled workers in Japan, and the resulting strife as Japanese nationals treated them like second-class citizens.

“It was interesting work, I was interviewing dentists from Sao Paolo who were making three times as much in Japan painting cars for Toyota or Nissan,” Ishiwata said. “But at some point I said, ‘Why am I flying all the way to Japan when there are problems going on in my own backyard?’”

African refugees

Some of Ishiwata’s CSU students from Greeley had told him about an influx of East Africans there, where they were employed in the local meat-processing plant run by JBS USA. Primarily hailing from Somalia and Ethiopia, these employees had been granted refugee status and a right to work in the U.S. by the federal government.

In Fort Morgan, where about 60 percent of the workers at the local Cargill meat-processing plant are Latino, more job applications began flowing in from East African refugees, who found favorable living conditions, strong social services and a job that pays a living wage in Colorado. In 2005, less than 1 percent of Cargill’s workforce was African; today it’s about 30 percent.

But as might be expected in a largely white, traditional and conservative rural community, the integration of the East Africans, many of whom are Muslim, was less than seamless.

“There was some animosity and very little experience dealing with foreign-born populations,” Ishiwata said.

Still, Fort Morgan has taken a proactive, positive approach to helping the three major populations — East Africans, Latinos and Caucasians — better understand each other.

OneMorgan County, a nonprofit organization started by Morgan Community College to offer citizenship and English classes to Latinos, joined forces with leaders from the school district, police department and Cargill to build bridges between the seemingly disparate cultures. They held forums for the newcomers on everything from how to obtain bank services to health care to housing.

When a possible conflict arose around accommodating Muslim prayer in school, the superintendent created a common-sense policy that allowed schools to make accommodations as long as they didn’t disrupt instruction, such as allowing prayer during breaks or lunch.

Cargill’s contributions

Cargill, the biggest employer in the county, played a significant role in helping its foreign-born workers acclimate to their new home — and helping the town adjust to their presence.

The company hosted weekly fairs where community members came to the plant to discuss topics with the new hires, such as setting up utilities, using on-site educational opportunities like English classes, and finding local sources for donated food, clothing and household goods. The company distributed maps, coupons from local businesses, and a publication on the basics of living in an apartment or rental house (how to use home appliances or talk to landlords about leases, for instance).

“Cargill has really gone beyond the industry standard,” Ishiwata said. “They recognize that the community is affected by their workforce. They’ve gone above and beyond to smooth out any tensions or rough spots in the community because of their workers.”

The Fort Morgan approach, which is now held up as a model for race relations, became Ishiwata’s research focus. And he was no detached observer; he has been involved in the efforts, acting as a consultant and forum facilitator since 2013.

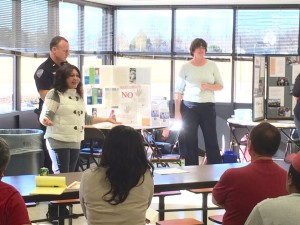

Ishiwata, left, meets with his team of students before the Feb. 7 meeting in Fort Morgan. Photo by Rachael Johnson

“The community-based participatory research that Dr. Ishiwata is engaged in is at the core of what we do in the Ethnic Studies Department,” said Irene Vernon, chair of the department, which is in CSU’s College of Liberal Arts. “The value of this type of research is well-recognized, and its success requires a high level of collaboration to address community needs. Dr. Ishiwata has been able to achieve this. He has been integrated and achieved a balance between research and action for the mutual benefits of all partners in this project.”

Cargill’s human resources manager, Mary Ginther, also lauded the role of Ishiwata and his students.

“Eric has provided guidance on what other integrated progressive communities in the U.S. and Canada had done to address the cultural differences present in their communities,” she said. “He has and continues to be a resource for us. His students help facilitate the discussions as well as serve as a role models for the youth in our community. At one such session, several African female CSU students helped facilitate a discussion between a young African female in our community and her parents about going to college in the U.S. The parents could see that some of their fears about their daughters leaving home to go to college and forgetting their customs and religion were unfounded.”

Bumps in the road

But it has not always been smooth sailing.

There have been incidents that the media has characterized as “hate crimes,” including vandalism in refugee neighborhoods. In early 2014, graffiti messages appeared, urging the East Africans to “go home,” and several car windows were shot out.

Fort Morgan Police Chief Darin Sagel, left, discusses the community relations work with CSU ethnic studies student Luis Rodriguez.

Ishiwata redoubled his efforts and involved even more of his students, including students with backgrounds similar to the groups living in Fort Morgan. When a fundraising effort to compensate the vandalism victims for repairs generated more money than was needed, OneMorgan County used the remainder to host a series of “Community Safety Through Education” forums. Ishiwata and his students have been involved in facilitating these forums, undergoing a training session with a U.S. Department of Justice conciliation specialist before a Nov. 1, 2014, workshop.

Tizita Tadesse, a CSU ethnic studies student who came to the U.S. from Ethiopia when she was 2 years old, was one of the facilitators at the session.

“They felt like we were there to support them and not hinder them,” she said. “We built that trust in a short time. It was a healing thing. We need to understand each other’s cultures. We can’t expect assimilation right away; we need to allow time for that.”

Another of Ishiwata’s students, Luis Rodriguez, helped translate for Spanish speakers at the event.

“It allowed me to see firsthand what I’m learning in the classroom,” he said.

Additional workshops

Since then, a couple of forums have featured the police chief and local attorneys discussing immigrant rights — and assuring those community members without documentation that reporting a crime to local authorities will not get them deported.

Fort Morgan residents Nimo Elmi, left, and Khadro Abdi at the Feb. 7 workshop.

CSU officials have also held workshops to answer questions about admissions, financial aid and campus resources — clearing up any misperceptions among the newcomers that college is out of reach.

“It was cool to come here and see what we’ve learned in class totally come to life,” communication studies student Laura Buser said after participating in a Feb. 7, 2015, workshop.

Namuyaba Temanju, an ethnic studies graduate student who speaks Swahili, is helping make inroads among the Somali women in Fort Morgan, a segment of the population that has been underserved to this point.

“Basically we need to improve communication and education on each side about what is the norm for them,” she said. “It’s a good opportunity for people to meet others they aren’t used to and learn something new.”

Michaela Frank, who worked with Ishiwata in Fort Morgan before graduating from CSU with a master’s degree in anthropology in May 2014, is now the director of OneMorgan County. Two current ethnic studies students, Taylor Stone and Aynadis Alemayehu, held internships with the nonprofit this year.

International music fest

Most recently the students helped organize the games at OneMorgan County’s International Music Festival held April 18 at the local high school. The activities, borrowed from a variety of cultures, ranged from cornhole to kendama, a Japanese game in which one tries to flip a tethered ball into a small cup on the end of a stick. The CSU students facilitated interactions between members of different ethnic groups, having them teach each other how to play the various contests.

But Ishiwata gives all the credit to the residents of the town.

“The hero is the community, and I’m always awed by the choices that community makes,” Ishiwata said. “It has weathered the storm, and now there is a tolerance there and an understanding that this is the new Fort Morgan.”

For Ishiwata, the research is personal. He is the son and grandson of immigrants.

“I just wonder how much more they could have accomplished or contributed if they’d had a more accommodating and inclusive community,” Ishiwata said. “I view my role, as an academic, as trying to use the privilege that I have in my position, and the resources I have access to, to try to make lives easier for this new generation of newcomers.”

“In this project I see the experience of my parents and grandparents,” he concluded. “That’s why I do this work.”

Scenes from the OneMorgan County International Music Festival that CSU’s Eric Ishiwata and his students helped run on April 18 in Fort Morgan. Photos by Heldwin Brito

Media assets

(Click on any photo above for a high-resolution version)

Video

Broadcast-quality version of the video via Vimeo

Video without graphics via Vimeo