It’s not often someone admits a project is in the toilet. But for John Mizia, a research associate at the Energy Institute at Colorado State University, his really is.

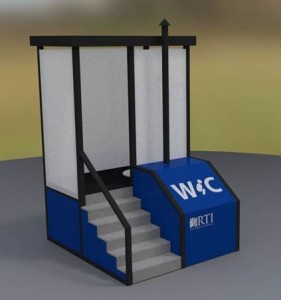

Mizia is working with scientists from North Carolina’s Research Triangle Institute and Duke University to engineer a toilet system for the developing world that requires no electricity or sewer infrastructure, sanitizes human waste and is easy to maintain.

Mizia and his CSU colleagues deal with a lot of the poop – they are designing and testing the system’s combustion chamber which incinerates, and thus sanitizes, human feces.

“We burn poop,” he said. “Our job is to find the best way to do it.”

CSU got involved in the project about two years ago.

RTI received a grant through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to design and build a prototype stand-alone waste sanitation system that disinfects urine, dries and burns feces and then converts the resulting combustion energy into stored electricity. The idea was one of 22 projects funded during the first round of the nonprofit’s “Reinventing the Toilet Challenge.”

The Gates Foundation launched the initiative to develop “next generation” toilets that could operate in areas with no sewer infrastructure or electricity and help bring reliable, safe, and affordable sanitation to the 2.5 billion people worldwide who don’t have it. Many are forced to openly defecate, tainting water, soil and food supplies with bacteria, viruses and parasites.

Poor sanitation is a significant health risk – especially for children. It can cause chronic diarrhea, which impedes a child’s ability to absorb essential nutrients. The condition can hinder a child’s development and even cause death. Chronic diarrhea is the second leading killer of children in the developing world, according to the World Health Organization.

It was CSU’s expertise with re-designing and testing cookstoves for the developing world that landed Energy Institute researchers a role in the project.

“(RTI) called us because we’ve gotten really good at burning all sorts of biomass through our cookstoves work,” Mizia said. “We’ve burned cow dung, salted wood, corncobs, charcoals, coconut husks, you name it.”

Pelletizing poop

Though Mizia and other Energy Institute researchers have burned biomass for years, they had never tried charring any feces other than cow manure, which has long been used a cooking fuel in the developing world.

At first, they used a “surrogate” human feces recipe provided to the teams participating in the toilet challenge which was based on miso paste. But the imitation stuff didn’t cut the cheese so the CSU researchers turned to a more advanced surrogate readily available in Fort Collins – dog poop.

They collected poop from their pets and brought it to the CSU  Engines & Energy Conversion Laboratory on North College to learn the best way to burn it.

Engines & Energy Conversion Laboratory on North College to learn the best way to burn it.

The team quickly found out is that shape is everything.

“The smaller and more condensed it is the better,” Mizia said.

They invested in a commercial meat grinder so they could shape the feces into a pellet-like form so it would dry faster and burn easier. The concept is similar to pellet-burning stoves that people use to heat their homes.

Pelletizing the poop worked so well the feature was incorporated into the toilet system’s design – before the combustion system burns the feces, an auger-like device breaks up the waste. This also allows the toilet, which can only hold eight ounces of poop at a time, to dispose of solid waste faster.

“This toilet doesn’t flush waste away like our sanitation system,” Mizia said. “It is self-contained so the waste stays there until it can be burned. It needs to dry as fast as possible so it can be disposed of quickly.”

Minimizing emissions

Understanding how to burn human-like poop is only one of the challenges for the CSU team.

Researchers spent considerable time designing and testing a combustion chamber that can incinerates feces while minimizing emissions. The chamber also must harness the combustion energy so it can be stored as electricity and then power the toilet’s ignition system, combustion blower and urine disinfectant systems.

It also had to be low-cost (the Gates Foundation requires the systems to operate for less than 5 cents per person per day) and easy to maintain.

“It’s a tall order,” Mizia said. “Making a low-emissions combusting toilet that can also disinfect urine requires a lot of energy. This combustion chamber has to be able to do a lot.”

The team went back to its roots and began testing a semi-gasifier combustor design – the same system used in the CSU-developed cookstoves. The gasifier technology is one of the lowest particulate and emissions emitting biomass combustors around. (The combustion process is much more controlled so the chemical kinetics can be steered away from high-emission operating regions.)

Toilet training

CSU researchers travelled to India last spring to help their colleagues assemble and display the combustion-based system at a toilet fair that included other Gates-funded potty projects.

Their system, one of the few that relies on burning feces to sanitize it, is moving into phase two – or in this case, number 2 – which involves field testing.

This spring, Mizia and others will return to India to set up the system and test how well it actually works and whether it is a viable design.

There is much to be done before then – including testing it with human waste, not just surrogates.

The research team is trying to work out the best way to do that. Researchers at RTI have burned human waste at their facility but the combustion expertise ultimately resides at CSU.

“We are trying to figure out how to proceed,” Mizia said. “We have burned several kilograms of animal feces at CSU but need to transition to human feces – it’s a different animal altogether.”

Whatever happens, Mizia and his CSU colleagues will be prepared for the field test. They’ve come a long way in their understanding of how to burn human poop.

“We’ve learned more about how to burn poop and do it cleanly than we thought possible,” he said.