[masterslider id=”99″]

More than 70 years ago, during the New Deal, the U.S. government took an unprecedented step toward preserving Native American art: It funded an effort to repair and replicate scores of totem poles in southeast Alaska, relocating them to six “totem parks.”

Now a Colorado State University faculty member is documenting that historic move, and the role that the 121 totem poles have played since then — from being key narratives for enduring Native cultures to serving as evidence for tribes’ claims to land that had been taken by the U.S. government.

Emily Moore, an assistant professor in CSU’s Department of Art and Art History, received a prestigious National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Stipend Award this year to help her complete a book and video project about the totem poles.

Ties to home

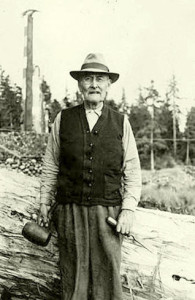

For Moore, it’s personal. She grew up in Ketchikan, Alaska, which is home to two of the six totem parks. Moore has also worked closely with the Tlingit and Haida tribes to preserve this chapter of their history. From 1938 to 1942, the U.S. Forest Service employed Native men to restore or replicate the 19th-century totem poles in a Civilian Conservation Corps program. Historically, Moore said, Native peoples had been encouraged by missionaries and others to burn their totem poles.

“It was the largest act of government patronage of Native American art in the 20th century, and it’s never really been studied,” said Moore, who is not Native but has been formally adopted into the Tlingit Kiks.ádi clan. “It was an about-face in government policy, an effort to preserve history that had been condemned. And you saw this transformation in the government officials, from a very prejudicial viewpoint where they called Native people ‘squaws’ and questioned their competence to a place where some of them actually became friends with Native carvers.”

She added that the NEH stipend she received for the project was an encouraging sign that Native art is now being taken more seriously.

“I was happy for the NEH award, but also glad that Native art is being recognized,” Moore said. “I was excited to get the stipend because so much Native American art hasn’t been represented in art history.”

Etched evidence

Moore, whose project began as her dissertation while earning a Ph.D. in art history from the University of California, Berkeley, said one of the most striking parts of her tale is that by funding the preservation of the totem poles, the U.S. government was actually strengthening the tribes’ case for laying claim to Native lands that had become the Tongass National Forest. Each totem pole relates to a story about clan history, and was often grounded in particular places that the clan used and owned. These oral histories — and the totem poles that recorded them — were later used as legal evidence that the Tlingit and Haida deserved compensation for the federal government’s 1909 takeover of those lands, a settlement they finally received in the 1960s.

Totem poles would traditionally have been placed in front of Native homes or in gravesites along the waterfront, identifying their owners with the crests of animals or other beings that were carved into the wood. Some totem poles acted as mortuary or memorial posts to the dead, while others were heraldic or storytelling poles. All poles represented crests that were owned by individual clans.

Job creation

Placing the poles in the totem parks during the New Deal was not just an effort to educate the public about Native heritage, but to give Natives employment designed to continue in the form of providing goods and services to tourists visiting the parks. Some have characterized the effort as a largely meaningless project to create jobs, but in her research, Moore found that the totem parks have actually made a valuable cultural contribution, from serving as a site for Native ceremonies to teaching new generations about ancient traditions.

“They all have iPhones and the Internet, but they’re also still carving totem poles,” she said. “My main point is that the poles weren’t inauthentic; they played an important role and continue to do so for communities today.”

Moore used the $6,000 stipend to devote her summer to the research project, paying for child care so she could write and traveling to Alaska for additional research at two totem pole raisings. The money also helped fund a video she is producing with a Haida filmmaker that will be used by the publisher, the University of Washington Press, as an online companion to the book.

The title of her book, For Future Generations: Tlingit, Haida and American Art in Alaska’s New Deal Totem Parks, makes use of the phrase that Natives often wrote on agreements signed with the U.S. government to authorize the totem park project: “For future generations.”

Good fit at CSU

Moore, who was hired by CSU in 2013, said she feels right at home in the Department of Art and Art History, where the majority of faculty are experts on non-Western art.

“That’s why I’m so excited to be at CSU, because they wanted Native American art history to be part of the curriculum,” she said. “My own experience as an art history major was that no one talked about Native objects as ‘art,’ but now more and more people recognize the complexity and beauty of these art forms.”

Moore’s book is expected to be finished by next summer. The Department of Art and Art History is part of CSU’s College of Liberal Arts.