A Colorado State University neuroscientist is using state-of-the-art imaging technology to better understand brain circuits that underlie eating disorders in hopes of helping people with anorexia and obesity.

Shane Hentges, an associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, wants to discover whether normal brain functions go awry in cases of anorexia and obesity – an understanding that could suggest new ways to prevent and treat these serious health problems. Nearly 2 billion people worldwide are overweight or obese, according to the World Health Organization.

A $150,000 grant from the Monfort Family Foundation allowed Hentges to recently acquire CLARITY imaging technology, which was developed by a team at Stanford University and is giving neuroscientists new ways to effectively examine inner workings of the brain.

CLARITY technology turns whole mouse brains transparent while preserving molecular structures inside; microscopes then may be used to investigate complete neuron networks, rather than parts of those networks. The approach provides a full and detailed view that was not earlier possible.

Mapping the neuron highway

“We need to map out the entire neuron pathway so we can see exactly what goes wrong in cases of obesity and anorexia,” Hentges said.

In 2014, she was named a Monfort Professor, an honor for up-and-coming CSU faculty whose research shows promise in addressing societal concerns. With her grant money, Hentges bought leading-edge microscope equipment and software that reveals, at high resolution, neuron function within intact brains.

“We’re drawing a roadmap and asking, What kinds of cars are on this map and where they are going?” Hentges explained. “In conditions like obesity and anorexia, we want to be able to see whether or not something went wrong. Did one of these cars drive off the road? Where do the streets end for the neurons involved in these processes, and what do they do when they get to their destinations?”

Multiple factors contribute to obesity and anorexia, including social, emotional and psychological influences. Hentges believes neurons stop behaving normally when someone has maintained too high or too low a body weight.

“The imbalanced state becomes the body’s new normal,” Hentges said, “and changing it requires a lot more than willpower.”

A new picture of eating disorders

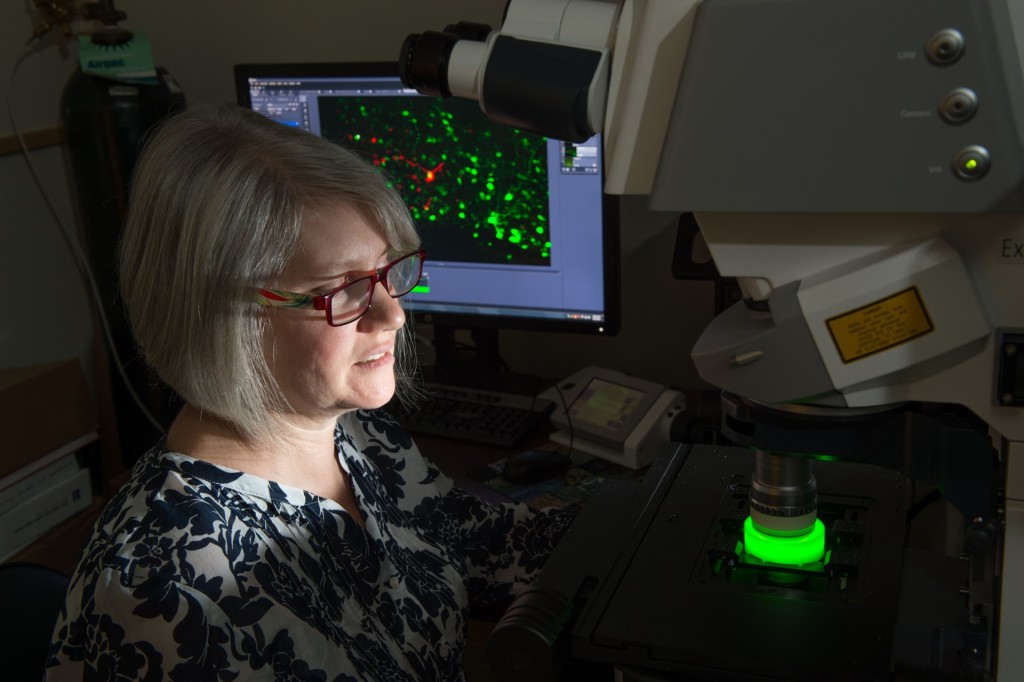

As the researcher discussed her work, a fluorescent green, three-dimensional image rotated in hypnotic circles on her computer screen. It was an image of neurons that stimulate food intake, along with their spindly fibers.

These neurons sit at the base of the brain, in the hypothalamus, and help regulate food intake and energy expenditure. When they don’t activate properly or at all, significant weight gain can result. With anorexia, these neurons appear to be hyperactivated and release a “don’t eat” signal.

“It would be an amazing step forward to actually be able to pinpoint some of the underlying mechanisms of an individual’s obesity or anorexia,” Hentges said. “We want to figure out what changes in the brain occur in response to these conditions so that we can help people.”

Her students, representing the next generation of neuroscientists, are equally excited to use new techniques for new insights into brain function.

“I first heard of the CLARITY method a couple years ago but never thought I would actually get to work in a lab that used it because it seemed so futuristic,” said graduate student Alex Miller, who works in Hentges’ lab.

Researchers across campus are working with her lab to advance their own work, Hentges said.

“The brain is by far the most complex organ system in the human body,” noted Colin Clay, head of the CSU Department of Biomedical Sciences. “Dr. Hentges’ work is laying the foundation for new approaches, not only to see the brain in unprecedented detail, but also to see how its complex network of over 100 billion neurons contributes to health and disease.”